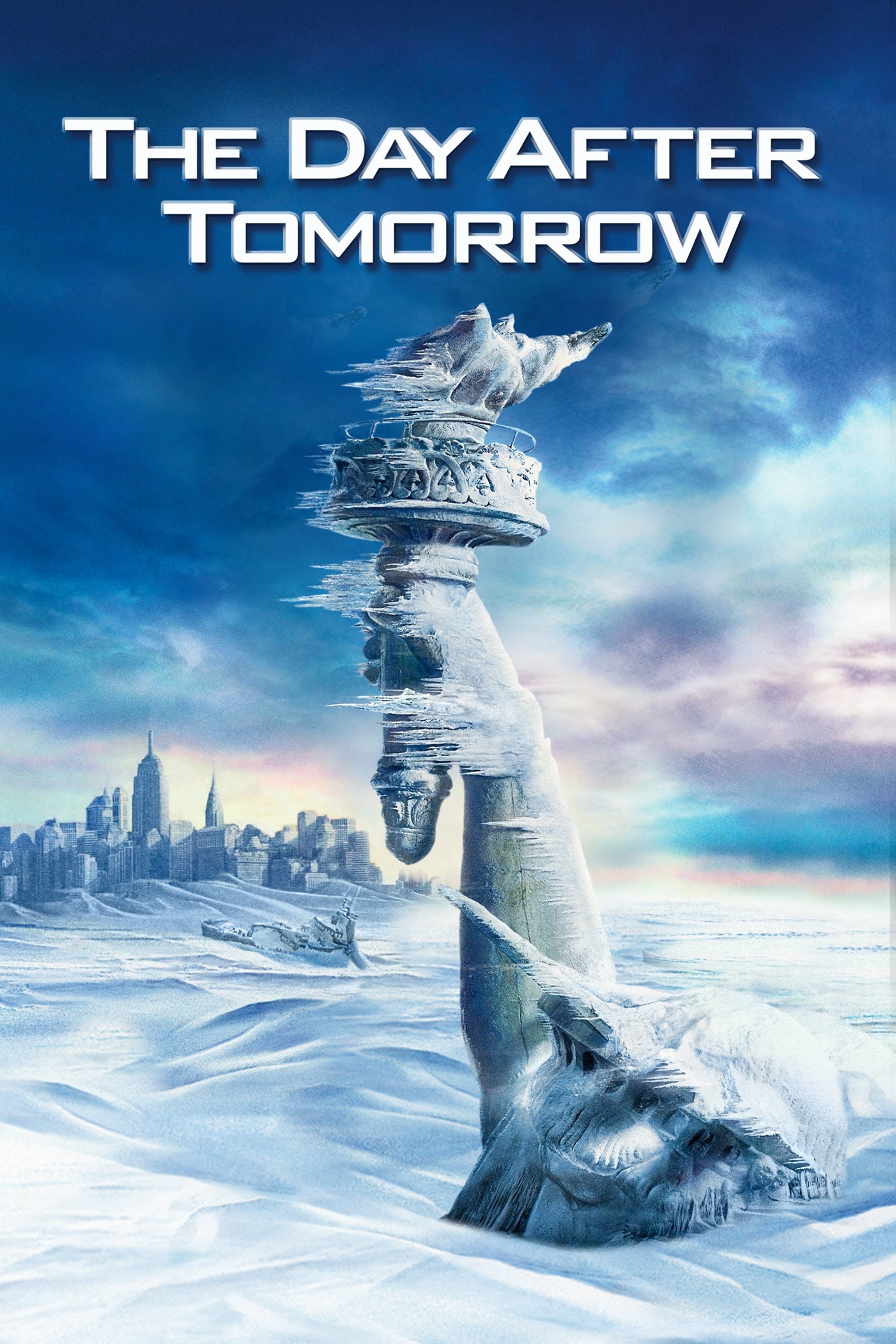

It’s hard to forget that image. You know the one—the Statue of Liberty buried up to her neck in ice, a silent, frozen sentinel in a New York City that’s turned into an Arctic wasteland. The Day After Tomorrow movie hit theaters in 2004, and honestly, it shouldn’t have worked as well as it did. We’re talking about a film where a paleoclimatologist (played by Dennis Quaid) literally outruns a frost line. It's ridiculous. It's scientifically "flexible," to put it lightly. Yet, here we are, decades later, and it still pops up in every conversation about climate change, disaster cinema, or why Roland Emmerich loves destroying landmarks.

The movie didn't just entertain; it scared a lot of people. It made the abstract concept of "global warming" feel immediate and visceral. Sure, the physics are wonky. No, the North Atlantic Current won't shut down in forty-eight hours. But the core anxiety? That stayed.

Why the Science in The Day After Tomorrow Movie Bothers Experts (and Why They Love It Anyway)

If you talk to a real climatologist about this film, you’re gonna get a mix of eye-rolls and genuine appreciation. The central premise revolves around the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). In the movie, the melting of the polar ice caps dumps so much freshwater into the ocean that it disrupts the "conveyor belt" of heat. This leads to a sudden, catastrophic drop in temperature.

In reality, scientists like Stefan Rahmstorf have pointed out that while the AMOC is slowing down, it’s not going to cause a "superstorm" that freezes a helicopter's fuel mid-flight. That part is pure Hollywood. The film suggests we could enter an ice age over a long weekend. Most peer-reviewed studies suggest these shifts take decades, if not centuries.

But here is the weird thing. The Day After Tomorrow movie actually did a favor for the scientific community. It gave them a vocabulary to talk to the public. Before 2004, terms like "thermohaline circulation" were relegated to dusty textbooks. After the movie? People were actually asking if the Gulf Stream was okay. It’s a classic case of a movie being factually wrong but emotionally right. It captured the scale of the risk, even if it messed up the speed.

The Dennis Quaid Factor and the Father-Son Trope

Roland Emmerich knows how to pull at your heartstrings while he’s blowing up the world. Jack Hall (Quaid) isn't just a scientist; he's a dad who wasn't there enough. His son, Sam (played by a very young Jake Gyllenhaal), is stuck in a frozen New York Public Library.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

The stakes are personal.

The movie spends a lot of time on Sam’s survival. He's trying to impress a girl (Emmy Rossum) while burning rare books to stay warm. It’s a weirdly cozy apocalypse. You've got the wolves escaping the zoo, the rising tide in the streets, and the sheer desperation of trying to find a working payphone. It works because we care about Sam getting back to his dad. Without that connection, it’s just a bunch of CGI ice.

The Politics of 2004 vs. Now

Looking back, the political messaging in The Day After Tomorrow movie was incredibly blunt. The Vice President character was a dead ringer for Dick Cheney. He’s the guy who dismisses the science because it’s "too expensive" to fix. It was a searing critique of the Bush administration’s environmental policies at the time.

There’s a scene where Americans are fleeing into Mexico to escape the cold. The irony wasn't lost on anyone then, and it certainly isn't lost on anyone now. The movie flipped the script on immigration and global power dynamics. It suggested that when nature turns, borders don't matter. It was a bold move for a summer blockbuster. Honestly, it’s a bit surprising a major studio leaned that hard into the social commentary.

Production Secrets: How They Froze New York

They didn't have the tech we have now. This was 2004. A lot of those massive shots of a flooded Manhattan were a mix of practical sets and early digital environments. They built a massive water tank in Montreal to film the street scenes.

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

- The production used over 250 tons of dry ice and artificial snow.

- The "hailstones" in the Tokyo scene were actually made of plastic and hand-thrown.

- Most of the "frozen" New York was created using a technique called photogrammetry.

The CGI has aged... okay. Some of the wolves look a bit like they wandered out of a PlayStation 2 game, but the storm surges still look terrifying. The sheer scale of the cargo ship floating down a flooded 5th Avenue is an image that sticks.

Is the "Big Freeze" Actually Possible?

We have to be honest here. A sudden ice age triggered by a storm is pure fiction. However, the weakening of the AMOC is a very real concern in 2026. Recent data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggests that while a total collapse is unlikely this century, the "tipping point" might be closer than we previously thought.

If the current slows, Europe won't necessarily freeze solid, but weather patterns will go haywire. We’d see more extreme heatwaves, different rainfall patterns, and yes, potentially harsher winters in specific spots. The Day After Tomorrow movie took a 10% reality and dialed it up to 1000%.

People often confuse this movie with 2012, another Emmerich flick. While 2012 was about neutrinos and crustal displacement (even more "fake" science), The Day After Tomorrow feels more grounded because we can see the ice melting today. It’s a warning wrapped in a popcorn flick.

The Lasting Legacy of the Film

Why does it still trend on streaming services every time there's a blizzard?

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Because it’s the ultimate "what if" scenario. It taps into a primal fear of the environment turning against us. We’ve built this massive civilization, but a few degrees' difference in the ocean can bring it all down. It reminds us we’re small.

The film also pioneered the "eco-thriller" genre in a way that Twister or Dante's Peak didn't. It wasn't just a local disaster; it was global. It changed how movies talk about the planet.

Survival Lessons from Jack Hall

If you find yourself in a The Day After Tomorrow movie scenario, the film actually gives some decent (and some terrible) advice.

- Don't go outside. This is the big one. If the "eye" of the storm passes over and the temperature drops to -150 degrees, you're dead in seconds. Stay inside, seal the doors, and burn whatever you can.

- Knowledge is power. Sam survives because he knows how to treat a wound and how to stay warm.

- Listen to the nerds. If a guy with a PhD tells you a wall of water is coming, maybe don't wait around to see it.

- The Library is a good choice. Lots of fuel (books), thick walls, and high ground.

To really understand the impact of this film, you have to look at how it shaped public perception. It didn't just sell tickets; it shifted the needle on how we view our responsibility to the Earth. It’s a movie that asks us to look at the sky and wonder.

Real-World Action Steps

If the themes of The Day After Tomorrow movie have you feeling a bit anxious about the real climate, don't just sit there. There are actual things you can do to stay informed and prepared for the real-world versions of extreme weather.

- Track the AMOC: Follow updates from organizations like NOAA or the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. They provide the actual data on ocean currents without the Hollywood dramatization.

- Audit Your Disaster Kit: You don't need to prepare for a global ice age, but having a 72-hour kit for local floods or storms is just common sense.

- Support Science Literacy: The best way to combat the "fake science" in movies is to understand the real science. Read the IPCC's "Summary for Policymakers"—it’s surprisingly readable and much scarier than any movie because it's real.

- Watch the Pacing: If you’re a filmmaker or writer, study how Emmerich uses "The Hero's Journey" to make a massive global event feel personal. It’s a masterclass in pacing a disaster narrative.

The world probably won't freeze tomorrow. But keeping a close eye on the thermometer—and the ocean—is probably a good idea. Take the movie for what it is: a thrilling, flawed, high-octane warning. Turn off the "science" brain for two hours, enjoy the spectacle, and then go out and do something to make sure it stays fiction.