He was broke. He was addicted. Honestly, he was lucky to be alive. By 1976, the man who had conquered the world as Ziggy Stardust was living in Los Angeles, subsisting on a diet of milk, red peppers, and enough cocaine to stop a horse's heart. He was paranoid, convinced that witches were trying to steal his semen and that UFOs were hovering over the Hollywood Hills. He needed an out. He needed to disappear. That desperate flight from the spotlight led him to a drafty, somewhat drab apartment in Schöneberg, West Berlin. What followed wasn't just a change of scenery; it was the birth of the David Bowie Berlin Trilogy.

Most people think these three albums—Low, "Heroes", and Lodger—were recorded entirely in Berlin. They weren’t. It’s one of those musical myths that just sticks. In reality, large chunks of this era were captured at the Château d'Hérouville in France or Mountain Studios in Switzerland. But the spirit of the work? That was all Berlin. It was the Cold War. The Wall was a physical, oppressive presence. Bowie, along with Brian Eno and Tony Visconti, wasn't just making pop music; they were dismantling the very idea of what a rock star should sound like.

The Myth of the Recluse

Bowie didn't go to Berlin to be a hermit. He went there to be a "nobody," which is a very different thing. In LA, he was a god. In Berlin, he was just some guy in a flat cap riding a bicycle to the grocery store. He shared a flat with Iggy Pop. Think about that for a second. Two of the biggest icons in rock history, living together in a run-down apartment, arguing over who bought the milk. It was during this period that Bowie helped Iggy produce The Idiot and Lust for Life, albums that are essentially the DNA of the Berlin sound.

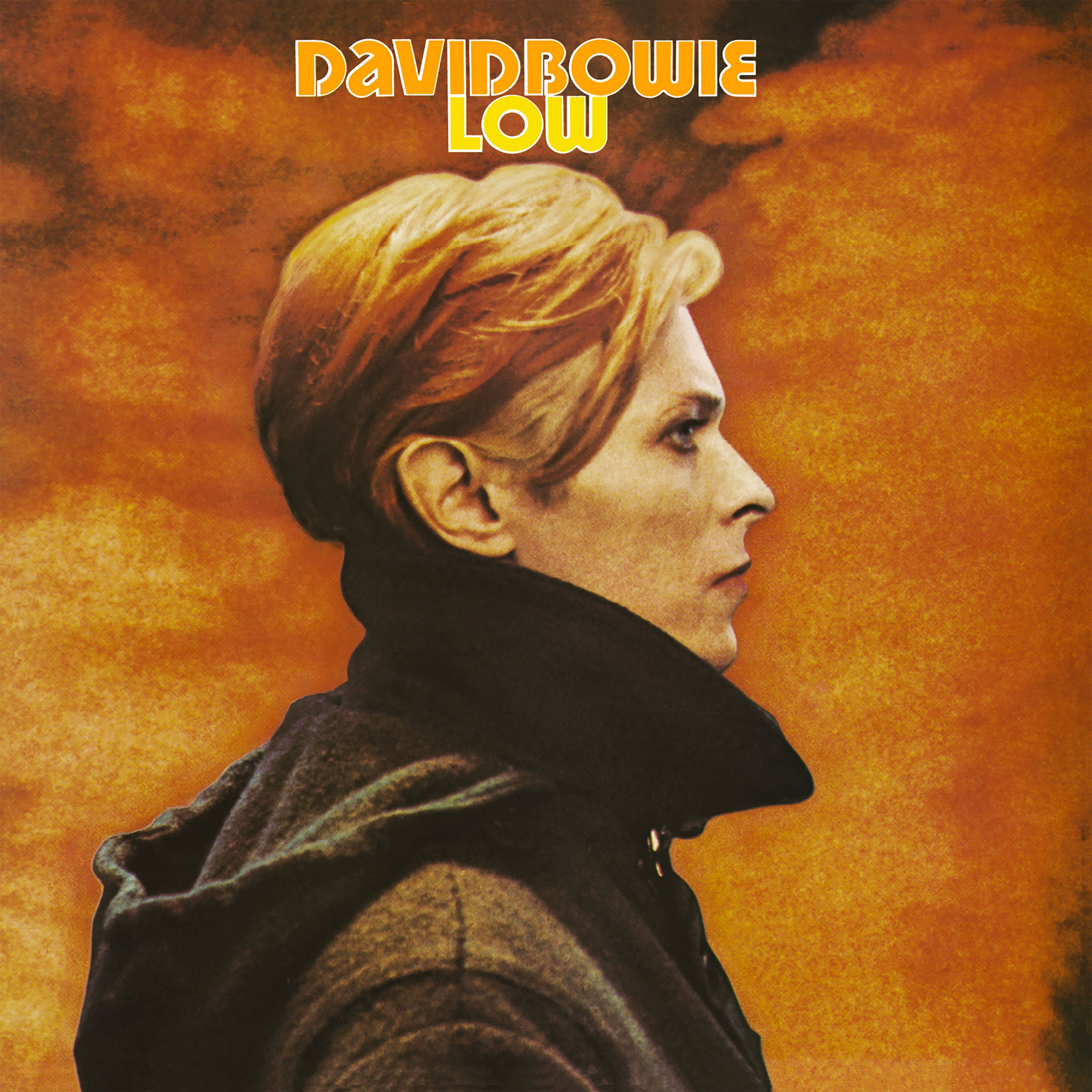

When Low dropped in 1977, the label, RCA, was horrified. They thought it was commercial suicide. The first half of the record is fragmented, jagged pop; the second half is a sprawling, ambient landscape of synthesizers and gloom. There were no "hits" in the traditional sense. It was cold. It was mechanical. It sounded like the future, but a future that felt a bit lonely.

The trick to understanding the David Bowie Berlin Trilogy is realizing that Bowie was trying to find a new way to write. He was bored with the "verse-chorus-verse" structure. With Brian Eno acting as a sort of sonic provocateur, they used "Oblique Strategies"—a deck of cards with cryptic instructions like "Look at the order in which you do things" or "Use an old idea." They were playing games with art.

💡 You might also like: Brother May I Have Some Oats Script: Why This Bizarre Pig Meme Refuses to Die

Breaking the Sound Barrier with Low and "Heroes"

Low was a shock to the system, but "Heroes" was the emotional core. Recorded at Hansa Studios, which was so close to the Berlin Wall that the guards could literally look into the control room windows, the album feels claustrophobic yet triumphant.

The title track is, arguably, the greatest thing he ever did. Everyone knows the story of the lovers by the wall, but fewer people realize that the "lovers" were actually his producer Tony Visconti and backing singer Antonia Maaß. Bowie saw them through the studio window. He turned a secret affair into a universal anthem for the marginalized.

Technically, "Heroes" is a beast. Visconti used a "gated" microphone technique to capture Bowie’s vocals. He set up three mics: one right in front of David, one fifteen feet away, and one at the far end of the hall. As David’s voice got louder, the distant mics would trigger, creating that massive, echoing wall of sound that feels like it’s swallowing you whole. It wasn't digital reverb. It was physics. It was the sound of a room screaming.

The Experimental Middle Ground

- The Instrumentals: Tracks like "Warszawa" and "Neuköln" weren't just filler. They were Bowie’s attempt to capture the atmosphere of Eastern Europe—a place he found fascinating and terrifying.

- The Gear: They weren't using high-tech workstations. It was an EMS VCS 3 synthesizer (the "Putney"), a joystick-controlled machine that Eno used to create "snake-like" sounds.

- The Influence: You can’t talk about this era without mentioning Kraftwerk and Neu!. Bowie was obsessed with "Motorik" rhythms. He wanted to sound like a machine with a human heart.

Lodger: The Odd One Out

Then there’s Lodger. Released in 1979, it’s often the forgotten sibling of the David Bowie Berlin Trilogy. It doesn’t have the ambient instrumentals of the first two. It’s messy, world-weary, and strange. Recorded in Switzerland and New York, it traded the Cold War chill for a sort of "global" paranoia.

📖 Related: Brokeback Mountain Gay Scene: What Most People Get Wrong

In Lodger, Bowie and Eno took their experiments to the extreme. For the song "Boys Keep Swinging," they made the musicians swap instruments. The guitarist played drums; the drummer played bass. They wanted that "amateur" energy—the sound of someone struggling with their tools. It’s an uncomfortable listen at times, but it’s brilliant. "Fantastic Voyage" deals with the looming threat of nuclear war, a theme that felt very real in 1979.

Critics at the time didn't really get it. They wanted another "Heroes". Instead, they got a record that sounded like it was falling apart at the seams. But listen to it now, and you’ll hear the blueprints for the next twenty years of indie rock. Bands like Talking Heads and Blur owe their entire careers to the risks Bowie took on Lodger.

The Lasting Legacy of the Berlin Era

Why does the David Bowie Berlin Trilogy still matter? Why do we keep talking about it forty-five years later?

It’s because it represents the ultimate "pivot." Most artists, when they hit a wall or a drug-induced breakdown, just fade away. Bowie didn't. He used his crisis as fuel. He stripped away the makeup, the costumes, and the ego. He proved that you could be the biggest star in the world and still be an avant-garde weirdo.

👉 See also: British TV Show in Department Store: What Most People Get Wrong

He also humanized the synthesizer. Before Low, electronic music was often seen as cold or novelty. Bowie and Eno showed that you could use a synth to express profound sadness, longing, and hope. They made the machines cry.

Actionable Insights for Music Fans and Creators

If you want to truly appreciate or draw inspiration from this era, don't just listen to the "Best Of" collections. Go deeper.

- Listen to the Trilogy in Order: Start with Low, then "Heroes", then Lodger. Notice how the sound shifts from internal isolation to external chaos.

- Check out the Context: Listen to Iggy Pop’s The Idiot immediately before Low. You can hear the same production techniques being "road-tested" on Iggy before Bowie used them for himself.

- Apply the Oblique Strategies: If you're a creator—whether a writer, painter, or musician—look up Brian Eno’s cards. When you’re stuck, use a random constraint. The best art often comes from working within limits.

- Visit the Hansa Meistersaal: If you're ever in Berlin, take the tour. Standing in the room where "Heroes" was recorded is a spiritual experience for any music lover. You can still feel the history in the floorboards.

The Berlin years weren't just a phase; they were a blueprint for survival. Bowie showed us that to move forward, you sometimes have to burn everything down and start over in a city that’s just as broken as you are. It’s not just music. It’s a manual for reinvention.