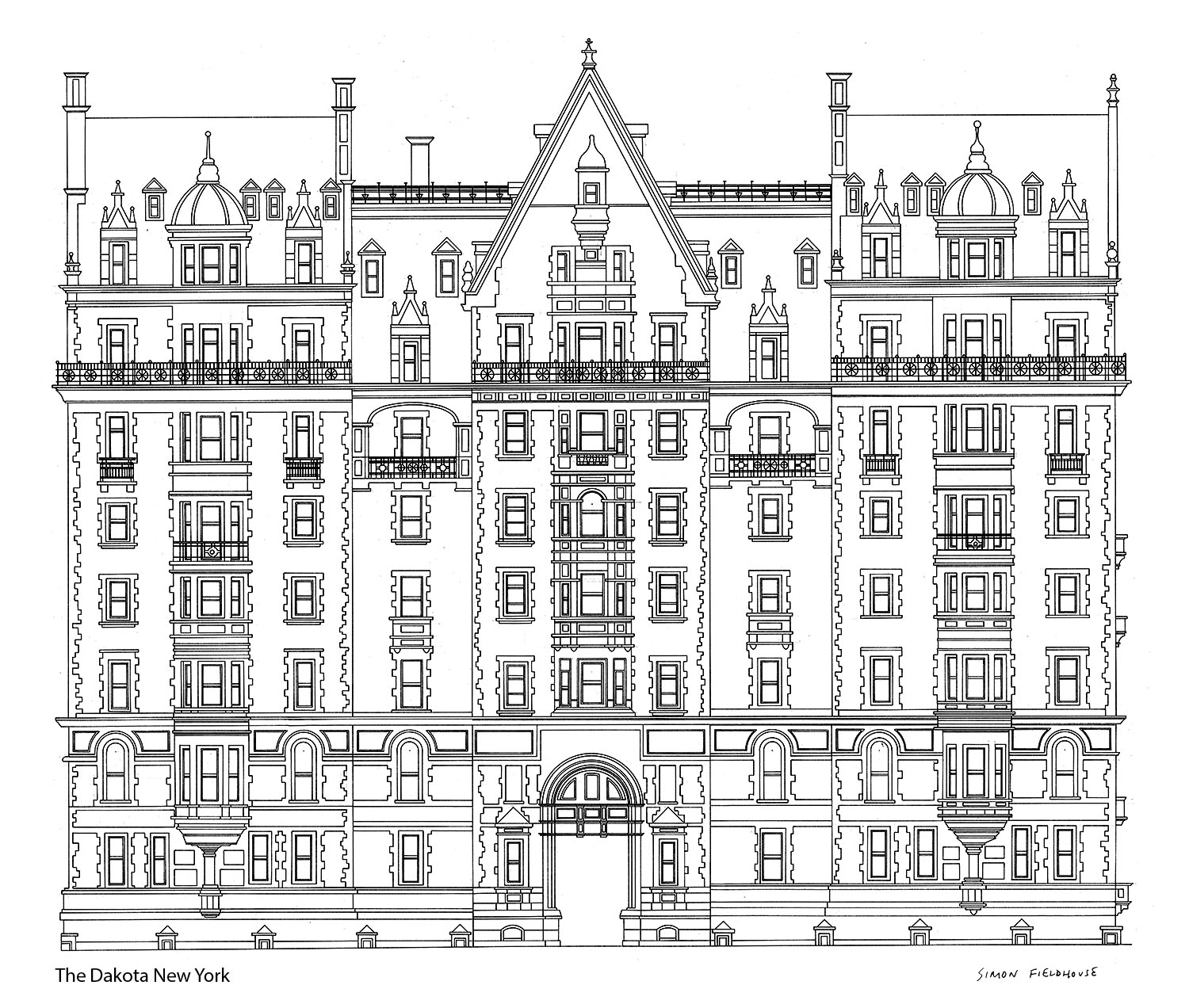

It sits on the corner of 72nd Street and Central Park West like a massive, gothic fortress. You've probably seen it. Maybe you stopped to take a photo of the arched gateway where John Lennon was killed. Or maybe you just felt that weird, heavy vibe it gives off. The Dakota New York isn't just an apartment building; it’s a fortress of old-school gatekeeping. Honestly, in a city where billionaires can buy almost anything, the Dakota is the one place that still says "no" to people with more money than God. It’s legendary. It’s creepy. And it is arguably the most difficult co-op to get into on the entire planet.

When Henry Janeway Hardenbergh designed it back in the 1880s, people thought he was nuts. At the time, the Upper West Side was basically the middle of nowhere. It was so far north of the city’s heart that critics joked it might as well be in the Dakota Territory. Hence the name. But Edward Clark, the guy who ran the Singer Sewing Machine Company, had a vision. He wanted a place that combined the space of a mansion with the convenience of an apartment. He got it.

What Actually Happens Inside the Dakota New York?

Most people think of the Dakota as a museum because of the Lennon connection. But for the residents, it's a living, breathing village. The layout is weirdly brilliant. Instead of one central hallway like a hotel, there are four separate entrances in the corners of the courtyard. This means you only share your elevator with a few other families. It’s private. Like, really private.

The ceilings are massive—some are 14 feet high. The walls are three feet thick. You could probably set off a firework in your living room and the neighbor wouldn't hear a peep. This was by design. In the late 19th century, "apartment living" was considered something for the poor or transient. To convince the wealthy to move in, Clark had to make the building feel more solid than a house. He used 4.5 million bricks. He used hand-carved oak. He used marble. Lots of it.

But here’s the kicker: it’s not just about the architecture. It’s the board. The Dakota co-op board is the final boss of Manhattan real estate. They don't care if you have a billion dollars. They don't care if you have a Grammy. In fact, if you have a Grammy, they probably want you even less because they hate "paparazzi magnets." They famously rejected Madonna in the 80s. Billy Joel? Rejected. Cher? Rejected. Antonio Banderas and Melanie Griffith? Nope. Even Alex Rodriguez—at the height of his Yankee fame—couldn't get a "yes."

The "Quiet" Wealth Requirement

To buy in the Dakota New York, you need a massive amount of liquid cash. We aren't just talking about the purchase price, which can range from $4 million for a "small" unit to $30 million or more for a sprawling masterpiece. You need to prove you have a staggering amount of money just sitting in the bank, and you can't finance the purchase. No mortgages. Zero. You pay cash or you don't play.

✨ Don't miss: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

Then there’s the interview. It’s basically a forensic audit of your soul. They want to know your social standing, your philanthropic history, and whether you’re the kind of person who throws loud parties at 2 AM. If you’re a "celebrity" who draws a crowd of fans to the sidewalk, you’re a liability. Yoko Ono still lives there, of course, but she’s grandfathered in—or grandmothered, rather. She’s been there since 1973.

The Architecture of Paranoia and Luxury

The Dakota New York was built with a courtyard that allowed carriages to drive right in. This meant the wealthy residents could step out of their carriage and into their private elevator lobby without ever touching the public sidewalk. It was 19th-century privacy technology. Today, it serves the same purpose for black SUVs.

The building used to be totally self-sufficient. It had its own power plant. It had a massive dining room where residents could eat if they didn't feel like cooking (the dumbwaiters would send the food up to the individual apartments). There was even a laundry and a staff of servants living in the upper floors. Those servant quarters have mostly been converted into "overflow" rooms or small apartments for the residents' current staff, but they still carry that sense of a bygone era.

Misconceptions About the "Hauntings"

Is it haunted? Depends on who you ask. The building’s reputation for the macabre started way before 1980. Roman Polanski filmed Rosemary’s Baby here in 1968, and that movie did more for the Dakota’s "spooky" reputation than any real-life event. The exterior, with its gables and gargoyles, just looks like the kind of place where a coven would meet.

People claim to have seen the "Crying Lady" or a young girl in yellow. Honestly, when a building is this old and has seen this much history, people are going to project stories onto it. The 1980 tragedy involving John Lennon is the only verified "dark" event that truly changed the building's energy. Since then, the security has been ironclad. You aren't getting past those gates unless you're expected.

🔗 Read more: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Why the Dakota Still Dominates the Market

You might wonder why anyone would deal with the Dakota New York's restrictive board when they could just go buy a glass penthouse on Billionaire’s Row. The answer is soul. The new buildings on 57th Street are sleek and tall, but they’re sterile. They feel like high-end hotels.

The Dakota feels like history.

Every apartment is unique. One might have original hand-painted shutters and silver-plated hardware; another might have been renovated into a minimalist white box (though the board usually hates that). There’s a level of craftsmanship that literally doesn't exist anymore because it's too expensive to replicate. You can't buy 140-year-old seasoned mahogany at Home Depot.

- The Fireplaces: Almost every major room has a fireplace. Originally, these were the primary heat source.

- The Windows: Massive, heavy, and designed to catch the breeze from Central Park.

- The Floors: The sub-flooring is filled with several inches of cork and sand to deaden sound. It works better than modern insulation.

The Reality of Living with History

Living here means you’re a steward, not just an owner. You can’t just go knocking down walls. The board has strict rules about renovations. They want to preserve the "integrity" of the building. This can be a nightmare for people who want a modern open-concept kitchen. In the Dakota, kitchens were originally seen as service areas, so they were often tucked away. Moving plumbing in a 19th-century brick fortress? Good luck with that.

There’s also the "look." The building is under perpetual maintenance. Because it's a landmark, every repair has to be done using specific materials and methods approved by the city. It’s expensive. The monthly maintenance fees alone can be more than most people's annual salaries. You're paying for the security, the staff, the history, and the sheer prestige of the zip code.

💡 You might also like: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

A Lesson in Manhattan Real Estate Power

The Dakota New York teaches us that real luxury isn't about what you have; it's about what you can exclude. The building has survived the Great Depression, the "white flight" of the 70s, and the rise of the glass skyscrapers. It remains the ultimate status symbol because it’s a closed loop.

If you're looking to understand the NYC property market, don't look at the prices first. Look at the boards. The Dakota is the blueprint for the "exclusive co-op" model that defines the Upper East and West Sides. It’s about social engineering as much as it is about real estate.

How to Experience the Dakota (Without a Board Interview)

Unless you’re a billionaire with a boring social life and a lot of patience, you’re probably not moving in. But you can still appreciate it.

- The Strawberry Fields Loop: Start at the Strawberry Fields memorial in Central Park. Look across the street. That’s the most iconic view of the building.

- Architectural Walk-by: Walk down 72nd street. Check out the ironwork on the gates. Look at the original gas lamps that have been electrified. The detail is staggering.

- Historical Research: If you’re a nerd for this stuff, the New-York Historical Society has incredible records of the building’s construction and the original floor plans.

The Dakota New York isn't going anywhere. It’s a literal rock. While the shiny towers of Hudson Yards might eventually go out of style, this place is permanent. It represents an era of New York that was bold, slightly eccentric, and unapologetically elite. It’s the closest thing the city has to a royal palace, even if the "royalty" inside are mostly reclusive hedge fund managers and the occasional aging rock star.

If you ever find yourself standing in front of those gates, take a second to look up. Ignore the tourists for a moment. Look at the brickwork. Look at the deep shadows in the gables. You’re looking at the building that invented the idea of a "luxury apartment" in America. It’s been copied a thousand times, but there is still only one Dakota.

To dive deeper into the history of the Upper West Side’s development, look into the life of Edward Clark. His decision to build on 72nd Street essentially shifted the center of gravity for New York's elite, proving that "location, location, location" is something you can actually create if you have enough bricks and enough guts.