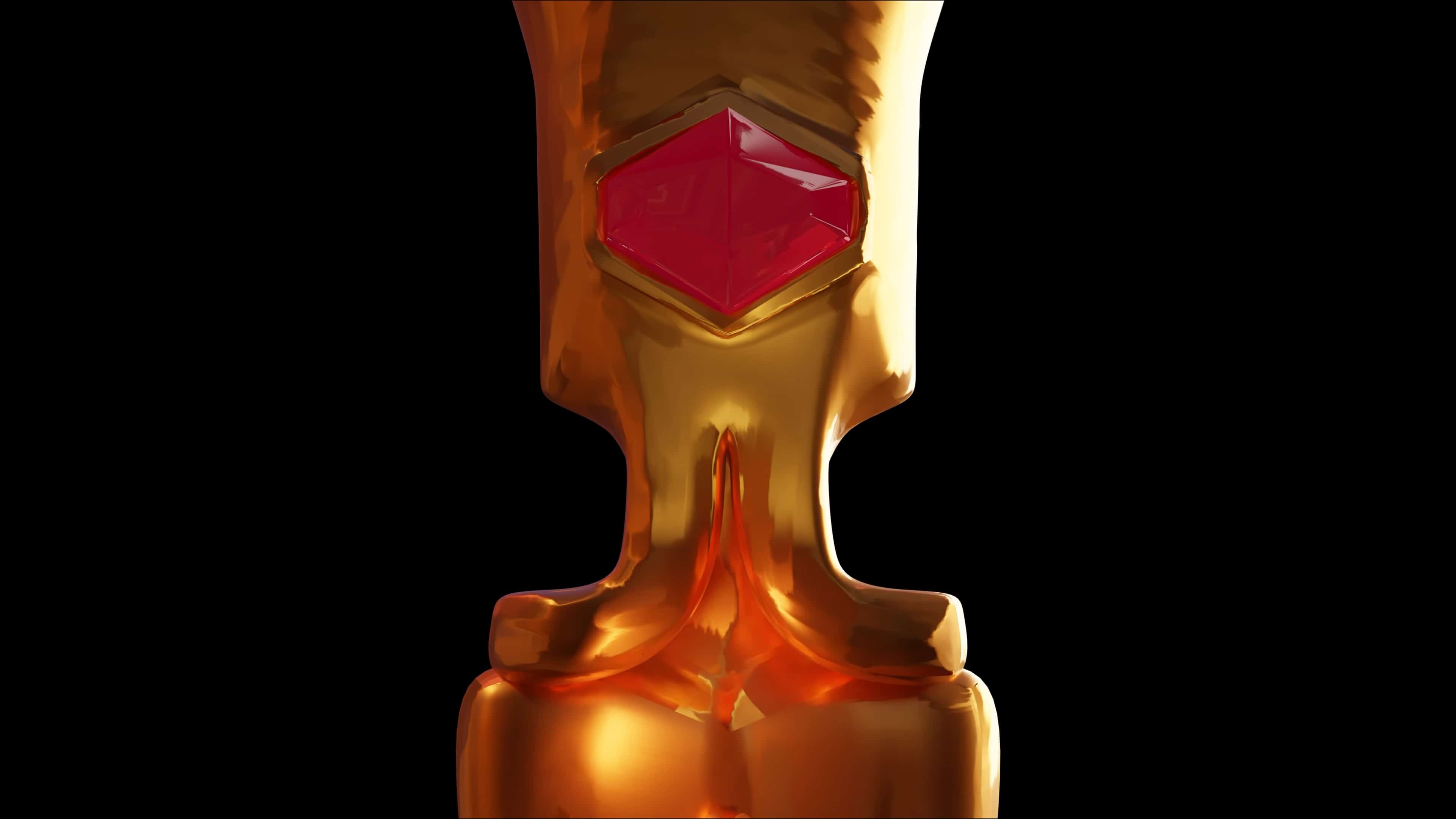

You’re staring at a frozen moment in time. A man is screaming, his skin is literally bubbling into a golden crust, and three or four other people in the room look like they’ve either just committed a murder or are about to be the next victim. There is no timer. No one is shooting at you. It is just you, a notebook of blank spaces, and a series of increasingly horrific events spanning centuries. Honestly, The Curse of the Golden Idol shouldn’t work as well as it does, but here we are. It’s a game that treats you like you actually have a brain, which is a rare commodity in modern gaming.

Most detective games hold your hand. They give you a "detective vision" that highlights clues in glowing neon, or they wait for you to click every object before moving the plot forward. Color Gray Games, the two-man team out of Latvia, took the opposite approach. They give you the scene—the whole, bloody, confusing mess—and tell you to figure out the "who, what, where, and why" using a drag-and-drop interface that feels more like filling out a mad-lib from hell than playing a traditional point-and-click adventure.

What makes The Curse of the Golden Idol so unsettling?

It’s the art style. Let's be real—the characters in this game are ugly. They are lumpy, sweating, toothy, and often caught in the middle of a grisly death rattle. This isn't the sanitized, "prestige TV" version of the 18th century. It’s gross. But that grotesque aesthetic serves a massive functional purpose: it makes every character distinct. When you’re trying to track a specific character across several decades of a family’s downfall, you need to remember that one guy with the bulging eyes and the specific facial mole.

The game follows the tragic, often darkly hilarious trajectory of the Cloudsley family and the titular idol. This isn't just a collection of random puzzles. It’s a 12-chapter saga (plus DLCs like The Spider of Lanka and The Lemurian Vampire) that explores how a single object of power can corrupt generations. You start in 1742. You end up much later, seeing the ripple effects of choices made in the very first scene. It’s the kind of storytelling that rewards you for paying attention to the background, like noticing a specific crest on a ring or a recurring name in a ledger.

The mechanics of "Thinking"

The core loop is simple: Explore mode and Thinking mode. In Explore, you click on everything. Pockets, letters, discarded notes, even the expressions on people's faces. This populates a word bank at the bottom of your screen. Then, you switch to Thinking mode. This is where the magic—and the frustration—happens. You have to slot those words into a narrative summary of the event.

👉 See also: Will My Computer Play It? What People Get Wrong About System Requirements

If you think "Sebastian" killed "Willard" with a "Dagger" because of "Greed," you plug those in. If you’re wrong, the game doesn't tell you which part is wrong. It just sits there, judging you. Or, if you’re close, it might tell you that two slots are incorrect. This forces a level of deductive reasoning that most games shy away from. You aren't just guessing; you’re building a logical proof.

Why the "Golden Idol" keyword matters for detective fans

If you loved Return of the Obra Dinn, you’ve probably had people scream at you to play this. Both games share a "freeze-frame" detective mechanic, but The Curse of the Golden Idol feels more like a political thriller. It’s about the rise of secret societies, the fragility of the British aristocracy, and the sheer stupidity of human greed.

The complexity of the "Spider of Lanka" and "Lemurian Vampire" expansions

The developers didn't just stop with the base game. They realized the community was hungry for more punishment. The DLCs actually ramp up the difficulty significantly. In The Spider of Lanka, the puzzles become more layered, involving complex cultural hierarchies and more sophisticated "Thinking" boards.

One of the best things about the DLC is how it fills in the blanks of the Idol's origin. We see how it wasn't just a random cursed object but something tied to a specific set of rules. The "Lemurian Vampire" DLC takes this even further, messing with your perception of time and identity in ways that make the late-game chapters of the original look like a tutorial.

✨ Don't miss: First Name in Country Crossword: Why These Clues Trip You Up

Common misconceptions about the gameplay

A lot of people think this is a "hidden object" game. It really isn't. You can find all the clues in thirty seconds, but it might take you thirty minutes to understand what they mean.

- The clues aren't always text. Sometimes the clue is the fact that a chair is knocked over, or that one person is wearing a disguise that matches a coat seen in a previous chapter.

- Names are everything. You’ll often find a list of names on a guest manifest and have to use the process of elimination to figure out who is who based on their belongings.

- It’s not just about murder. While there’s a lot of death, some chapters are about political maneuvers, thefts, or ritualistic ceremonies.

How to actually get better at the game

If you're stuck, the worst thing you can do is start "brute-forcing" the words. The word bank is too large for that. Instead, look for the "anchor" of the scene. Usually, there is one person whose identity is undeniable—maybe they have a name tag, a letter addressed to them, or they were in the previous chapter. Work outward from that person.

Also, read the letters. Don't just skim them for names. Read the tone. If someone is writing about a "traitor in our midst," look at the people in the room. Who looks nervous? Who is holding the evidence? The game is remarkably fair. It never cheats. Every single solution is backed by at least two pieces of corroborating evidence. If you feel like you're guessing, you've missed something.

The legacy of the Golden Idol

Since its release, we've seen a surge in "detective-logic" games, but few hit the same stride. The sequel, The Rise oF the Golden Idol, moves the setting into the 1970s, proving that the formula isn't tied to the 1800s. It’s the logic that matters. The "curse" isn't just a supernatural plot point; it's a metaphor for how information is lost, found, and manipulated.

🔗 Read more: The Dawn of the Brave Story Most Players Miss

Honestly, the game is a reminder that we don't need 4K ray-tracing to be immersed. We just need a good mystery and the agency to solve it ourselves. It’s gritty, it’s smart, and it’s one of the few games that makes you feel like a genuine genius when the "Case Solved" music finally hits.

Actionable steps for your first playthrough

To get the most out of your time with the game, avoid the temptation of looking up a walkthrough the moment you hit a wall. The satisfaction is entirely in the "click" of realization.

- Keep a physical notebook. Sometimes drawing a quick map of who was standing where helps more than the in-game UI.

- Pay attention to the year. The timeline is crucial. A character who is a young rebel in one chapter might be a grumpy old judge three chapters later.

- Check the pockets. Always check the pockets. People in the 18th century apparently carried their entire life stories in their coat linings.

- Use the hint system sparingly. The game has a built-in hint system that asks you questions to lead you to the answer rather than giving it to you. Use it only when you’ve truly exhausted your own logic.

- Look at the art transitions. When you move between "Explore" and "Thinking," look at the small animations. Sometimes the way a character shifts can give you a hint about their intent or state of mind.

The real "curse" is finishing the game and realizing there aren't many others like it. Once you've mastered the logic of the Cloudsley family, your brain will be wired to look for patterns in everything. It’s a short, sharp shock of a game that respects your time and your intelligence.