You probably think of your stomach as the star of the digestive show. It gets all the credit, the growls, and the "butterflies," but honestly? Your stomach is just a glorified blender. The real work—the heavy lifting of keeping you alive—happens further down the line. If you were to take a cross section of small intestine, you wouldn't just see a simple pipe. You’d find a landscape so complex and rugged it looks more like a topographical map of a mountain range than a piece of anatomy.

It’s tiny. It’s huge.

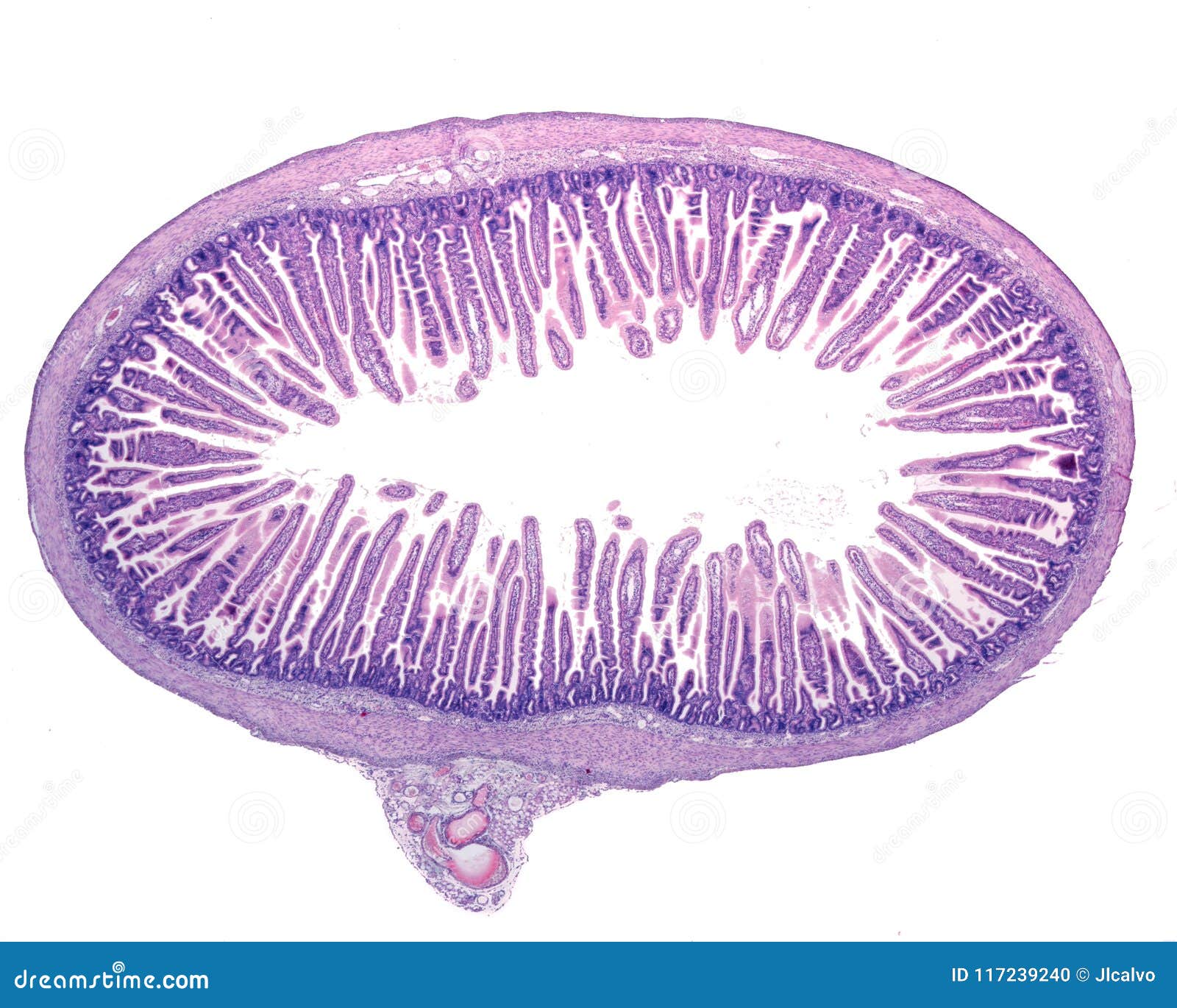

That sounds like a contradiction, right? But that’s the magic of the small intestine's architecture. While the tube itself is only about an inch or so in diameter, its internal surface area is roughly the size of a tennis court. Evolution didn't just give us a long hose; it packed a massive absorption factory into a tight, coiled space. When we look at a cross section of small intestine, we’re seeing four distinct layers of tissue—the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa—working in a frantic, beautiful synchronicity to turn that sandwich you ate into the literal fuel for your brain cells.

The Mucosa: Where the Magic Happens

The innermost layer, the mucosa, is where things get wild. If you slice it open and look under a microscope, you’ll see these finger-like projections called villi. They’re not just there for decoration. These villi are the primary reason humans can survive on a few meals a day instead of eating constantly like a hummingbird.

Think of the villi as a shag carpet. If you spill water on a flat linoleum floor, it just sits there. If you spill it on a thick rug, the fibers suck it up instantly. That’s the goal here: maximum contact. Each of those villi is covered in even tinier hairs called microvilli, often referred to as the "brush border." This is where enzymes like lactase and sucrase hang out, waiting to snap up sugars.

It's actually a pretty brutal environment. The cells on the tips of the villi are constantly being shredded and replaced. In fact, you replace your entire intestinal lining every three to five days. You are, quite literally, growing a new gut every week. This high turnover is why chemotherapy—which targets fast-growing cells—often causes so much digestive distress; it hits the intestinal lining just as hard as it hits the tumor.

💡 You might also like: Is Tap Water Okay to Drink? The Messy Truth About Your Kitchen Faucet

Why the Submucosa Is the Unsung Hero

Right underneath that busy mucosal layer sits the submucosa. If the mucosa is the factory floor, the submucosa is the shipping and receiving department. It's a thick layer of connective tissue packed with blood vessels and lymphatics.

Once the villi grab nutrients, they have to go somewhere. The capillaries in the submucosa pick up amino acids and sugars, while special vessels called lacteals handle the fats. But there’s something even cooler hidden here: the Meissner’s plexus. It’s a network of nerves that acts like a local manager. It doesn't need to check in with your brain to decide when to secrete more enzymes or move things along. Your gut has its own "brain," and a big chunk of it lives right here in this cross-section.

Muscularis and the Art of Moving Food

Movement is life. Without the muscularis layer, you’d be a stationary tube of rotting food. This layer is actually two different sets of muscles working at 90-degree angles to each other. One layer wraps around the tube (circular), and the other runs the length of it (longitudinal).

They perform a rhythmic dance called peristalsis. The circular muscles squeeze behind the food to push it forward, while the longitudinal ones shorten the path. But it’s not just a one-way street. There’s also "segmentation." This is where the intestine squeezes in random spots to slosh the food back and forth, making sure every single molecule of nutrients touches a villus. It’s like kneading dough.

Between these muscle layers lies another nerve network, the Myenteric plexus. This is the master of "The Gut-Brain Axis." When people talk about having a "gut feeling," they are talking about the massive amount of neurological data traveling from these muscle layers back up to the cranium.

📖 Related: The Stanford Prison Experiment Unlocking the Truth: What Most People Get Wrong

The Serosa: The Protective Shield

The outermost layer of our cross section of small intestine is the serosa. It’s a thin, slippery membrane that secretes a tiny bit of fluid. Why? Because your intestines are essentially twenty feet of wet rope crammed into a small bag. They are constantly shifting, sliding, and pulsing. Without the serosa providing a low-friction coating, your intestines would literally rub themselves raw and create "adhesions," which are basically internal scars that can lead to life-threatening blockages.

What Goes Wrong (and Why it Matters)

Understanding the anatomy helps explain why certain diseases are so devastating. Take Celiac disease, for example. In a healthy cross section of small intestine, those villi look like lush, tall grass. In someone with untreated Celiac, an immune reaction to gluten causes those villi to "blunt" or flatten out.

The tennis court turns into a sidewalk.

When the surface area disappears, it doesn't matter how much you eat; the nutrients just slide right past. This leads to malabsorption, fatigue, and bone loss. Similarly, Crohn’s disease can penetrate through all four layers of the intestinal wall, causing deep ulcers and fistulas. It’s not just "an upset stomach"; it’s a structural failure of a highly engineered biological machine.

Real-world clinical data from institutions like the Mayo Clinic suggests that gut health is increasingly tied to the microbiome—the trillions of bacteria living on that mucosal layer. These bacteria actually help "train" the immune system cells that live in the Peyer’s patches (small clumps of lymphoid tissue) found in the lower part of the small intestine.

👉 See also: In the Veins of the Drowning: The Dark Reality of Saltwater vs Freshwater

How to Actually Support Your Gut Anatomy

You don't need a "detox" tea or a fancy juice cleanse to help your small intestine. Your body is already doing the work. However, you can make the job easier for your internal architecture.

First, fiber is non-negotiable. While the small intestine doesn't "digest" fiber in the traditional sense, fiber helps regulate the speed of transit. If food moves too fast, you miss out on nutrients. Too slow, and you risk bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Second, hydration is the lubricant for the entire process. The serosa needs fluid to keep things sliding, and the mucosa needs water to produce the mucus that protects the cells from being digested by their own enzymes.

Lastly, pay attention to "transit time." If you feel bloated or sluggish, it might be that your muscularis layer isn't getting the right signals. Simple movement—like a 15-minute walk after a meal—actually helps stimulate those nerve plexuses we talked about.

Actionable Steps for Intestinal Health

- Prioritize Soluble Fiber: Foods like oats, beans, and peeled apples form a gel-like substance that slows down digestion just enough to maximize the "contact time" between food and your villi.

- Identify Your Triggers: If certain foods cause immediate bloating, you might be stressing the brush border enzymes (like lactase) in your mucosa. Keeping a food diary for just one week can pinpoint which structural part of your gut is struggling.

- Chew Your Food Thoroughly: This sounds basic, but your small intestine doesn't have teeth. The more you mechanical-breakdown food in your mouth, the less work the muscularis layer has to do to achieve "segmentation" and nutrient mixing.

- Monitor Your Iron and B12: Since these are primarily absorbed in specific sections of the small intestine (the duodenum and ileum), a deficiency here is often the first red flag that your intestinal "cross section" is experiencing inflammation or damage.

- Manage Stress: Because the enteric nervous system is so deeply embedded in the submucosa and muscularis, chronic "fight or flight" signals can literally shut down the blood flow to your gut, leading to long-term structural weakness.