Hergé was in a tight spot in 1940. Belgium was under German occupation, and the newspaper he worked for, Le Vingtième Siècle, had been shut down by the Nazis. He moved over to Le Soir, which was effectively a propaganda outlet at the time, but he decided to keep things light. He needed to avoid politics. No more Soviet critiques or Japanese imperialism. He just wanted to tell a story about a boy reporter and some smuggled opium. That’s how we got The Crab with the Golden Claws.

It’s basically the most important book in the entire Tintin canon. Not because the plot is particularly revolutionary—it’s a classic mystery involving tin cans and Moroccan deserts—but because of a certain drunken sailor. This is the book that introduced Captain Haddock. Can you imagine Tintin without Haddock? Honestly, it’s impossible. Before this, Tintin was a bit of a blank slate, a "boy scout" who always did the right thing. Haddock added the grit, the humor, and the human fallibility that the series desperately needed to survive the 20th century.

A Drunk, a Desert, and a Boat Named Karaboudjan

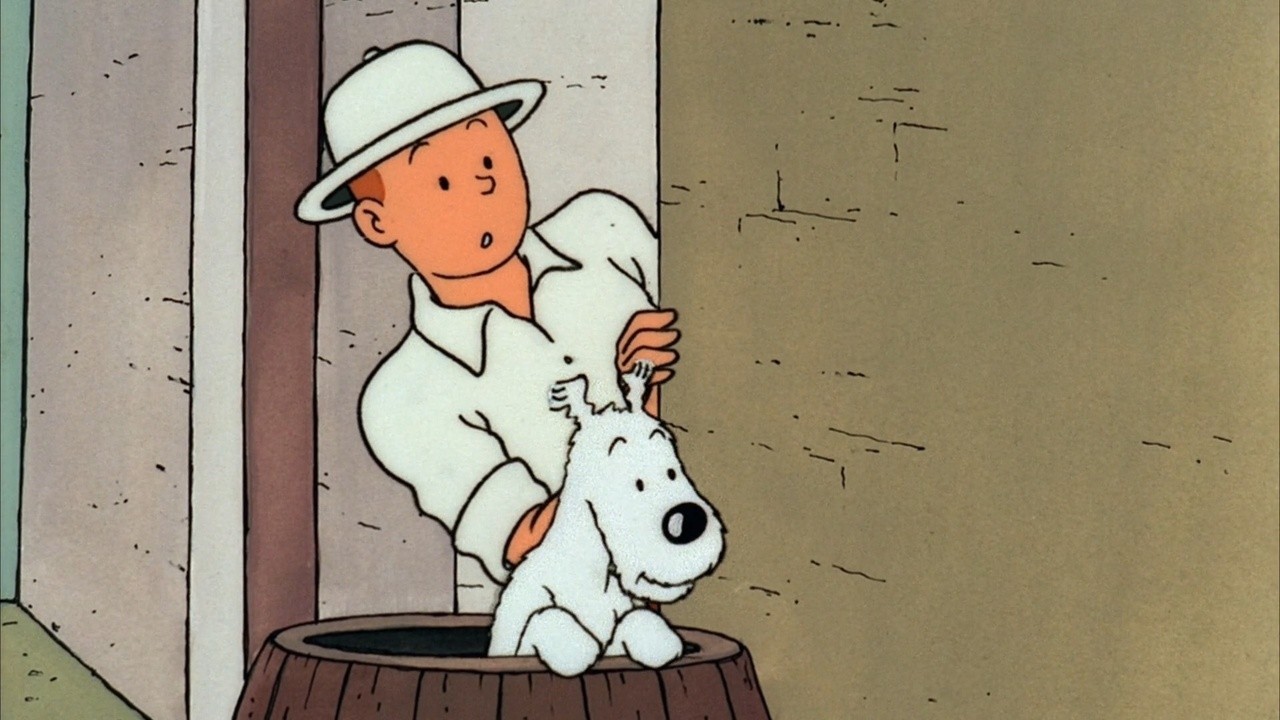

The story kicks off with a weirdly specific clue: a scrap of paper from a crab meat tin. Tintin, being Tintin, investigates and finds himself trapped on a cargo ship called the Karaboudjan. This is where he meets Haddock. But this isn't the heroic, blustering Captain we see in Red Rackham's Treasure. No, when we first see him in The Crab with the Golden Claws, he’s a total wreck. He’s a functional—well, barely functional—alcoholic being manipulated by his first mate, Allan.

Haddock is weeping in his cabin. He’s drinking whiskey while his crew runs a massive drug smuggling operation right under his nose. It’s actually pretty dark for a "children's book." Hergé didn't shy away from the reality of Haddock's condition. When they escape the ship and head into the Sahara, Haddock’s withdrawal symptoms and drunken delusions nearly kill them both. At one point, he thinks Tintin is a bottle of champagne and tries to "uncork" his head. It’s slapstick, sure, but it’s rooted in a very real, very messy character.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The pacing of the desert sequence is masterclass level. Hergé uses the vast, empty space of the Sahara to heighten the tension. You feel the heat. You feel the thirst. And then, the Berbers attack. It’s a chaotic, swirling mess of sand and gunfire. Unlike the earlier, more linear stories, this felt like a cinematic experience.

The Transition from Newspaper to Book

You have to remember that The Crab with the Golden Claws was originally serialized in Le Soir Jeunesse. Because of wartime paper shortages, the format was weird. It was published as a weekly supplement, and Hergé had to adapt his style to fit a smaller, more cramped layout. This actually forced him to become a better visual storyteller. He couldn't rely on long-winded dialogue. He had to make every panel count.

When the story was later colorized and reorganized into the 62-page format we know today, some of the most iconic frames in comic history were born. Look at the scene where Tintin and Haddock are walking through the dunes. The scale is massive. Hergé’s "ligne claire" (clear line) style reached a new level of maturity here. No hatching. No unnecessary shadows. Just clean, bold lines that tell you exactly what you need to know.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Why the Opium Plot Matters

Drug smuggling was a recurring theme for Hergé (think The Blue Lotus), but here it feels more like a MacGuffin. The "Golden Claws" aren't just a cool name; they represent the brand of crab meat used to hide the opium. It’s a classic noir trope. The mystery takes them from the docks of Belgium to the fictional Moroccan port of Bagghar.

Interestingly, Bagghar was based on real North African locales Hergé researched in travel magazines. He was obsessive about accuracy. If a building looked a certain way in Morocco, he wanted it to look that way in the book. This commitment to realism is what makes the more surreal elements—like Haddock’s hallucinations—pop so much. It’s a grounded world where un-grounded things happen.

The Censorship and the Cans

If you've ever read an American version of The Crab with the Golden Claws, you might have noticed some changes. Actually, the book has a long history of being nipped and tucked by editors. In the original version, there’s a scene where Haddock is being whipped by a Black character. When the book was brought to the U.S. in the 1950s, the publishers balked. They didn't want to show characters of different races interacting in a violent way, so Hergé had to redraw those panels to make the characters look "more Mediterranean" or vaguely Arabic.

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Then there’s the drinking. In some editions, the depictions of Haddock chugging whiskey straight from the bottle were toned down. It’s funny because Haddock’s alcoholism is the entire point of his character arc. Without the booze, his redemption doesn't mean anything. By the end of the book, he’s still a mess, but he’s Tintin’s mess. He’s found a reason to stay sober, or at least, a reason to be a better man.

How to Spot a First Edition (or a Good Reprint)

Collecting Tintin is a minefield. If you're looking for a copy of The Crab with the Golden Claws, you need to know what you're looking at.

- The 1941 B&W Version: This is the Holy Grail. It's the original format before the colorization. It feels much more like a noir film.

- The 1943 Color Edition: This is the one most of us grew up with. The colors are vibrant, but some of the gritty detail from the B&W version was lost.

- The Facsimile Editions: These are great because they recreate the original look and feel of the paper and ink from the 40s.

The value of these books has skyrocketed. A high-quality 1941 edition can go for thousands of dollars at auction houses like Artcurial. But for most of us, the standard Casterman paperback is just fine. The story holds up regardless of the paper quality.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you're revisiting this classic or introducing it to someone else, here is how to actually get the most out of the experience:

- Read it alongside The Blue Lotus. It’s fascinating to see how Hergé’s approach to "foreign" cultures evolved (and where it still stayed stuck in its time).

- Watch for the visual gags. Haddock’s first "curse" occurs in this book. He hasn't quite reached the "Billions of Blue Blistering Barnacles" peak yet, but he’s getting there.

- Check out the 2011 Spielberg film. A huge chunk of the movie is based directly on the desert sequence and the Karaboudjan escape from this book. Seeing those panels translated to 3D motion capture is wild.

- Look at the backgrounds. Pay attention to the crates, the street signs, and the architecture in Bagghar. It’s a masterclass in research-based illustration.

The Crab with the Golden Claws isn't just a comic book. It’s the moment a "kids' strip" became a sophisticated piece of literature. It gave us a flawed hero in Haddock and a sense of adventure that felt genuinely dangerous. It’s the perfect entry point for anyone who thinks Tintin is just for children. It’s messy, it’s sweaty, and it’s a little bit drunk. Just like Haddock.