History has a funny way of getting tangled up in poetry. You’ve probably heard the line—or at least a version of it: "Speak for yourself, John." It’s the ultimate 17th-century mic drop. That single sentence from The Courtship of Miles Standish basically turned a dusty historical footnote into one of the most famous romantic legends in American literature.

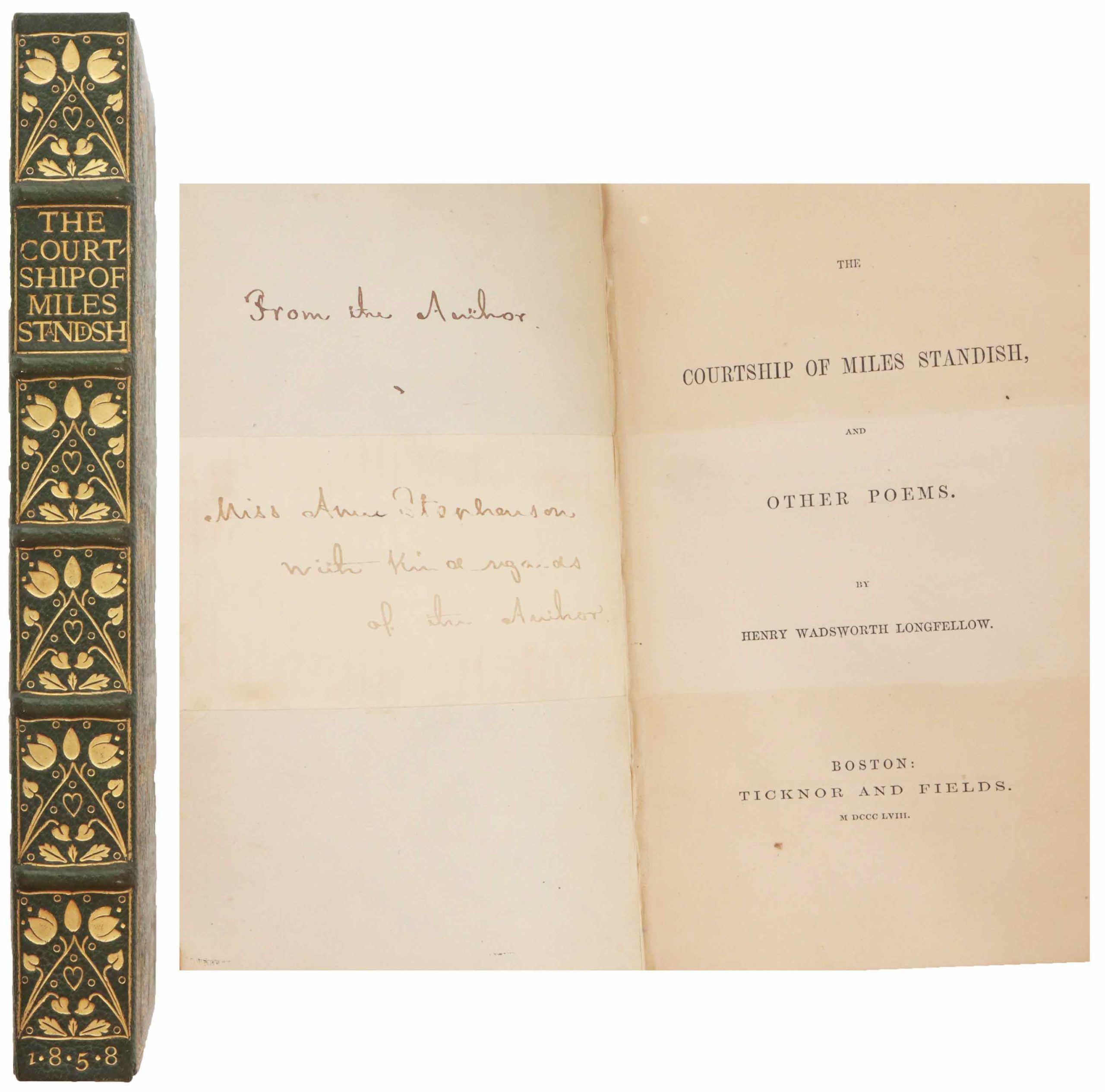

But here’s the thing. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the guy who wrote it in 1858, wasn't just some random poet looking for a theme. He was actually a direct descendant of the people he was writing about. Talk about family drama. He took a tiny scrap of oral tradition and blew it up into a narrative poem that sold 25,000 copies in its first two months. In the mid-1800s, that was the equivalent of a viral Netflix series.

Why The Courtship of Miles Standish Still Matters

Is it 100% historically accurate? Honestly, no. Not even close. But it matters because it shaped how Americans view the Pilgrims. Before this book, the settlers were often seen as somber, black-clad religious zealots. Longfellow gave them heart. He gave them jealousy. He gave them a love triangle that feels like something out of a modern sitcom, just with more muskets and spinning wheels.

The story centers on three real people: Miles Standish, the colony’s hot-tempered military leader; John Alden, a young, sensitive scholar; and Priscilla Mullins, a woman who had lost her entire family during that first brutal winter in Plymouth.

Standish is lonely. His wife, Rose, has passed away. He wants to marry Priscilla but he’s "a maker of war, and not a maker of phrases." So, he does what any brave soldier would do: he asks his best friend, John, to go propose for him. The problem? John is already head-over-heels in love with Priscilla himself.

📖 Related: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

The Cringe-Worthy Proposal

Imagine being John Alden. You’re forced by "duty" to tell the woman you love that your boss wants to marry her. He goes to her house, stammers through a speech about Standish’s virtues, and Priscilla sees right through it.

She doesn’t want the "old" soldier (who was actually only about 36 at the time, but in 1621, that was pushing it). She wants the guy standing in front of her. When she asks, "Why don't you speak for yourself, John?" she isn't just flirting. She’s asserting her own agency in a world where women were often treated like property to be negotiated.

Fact vs. Fiction: Sorting Through the Legend

While the poem is a masterpiece of Victorian sentiment, the real history is a bit more complicated. We know for a fact that John Alden and Priscilla Mullins did marry. They had ten children. They were founding members of Duxbury, Massachusetts.

But did the "stand-in" proposal actually happen?

👉 See also: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

- The Source: Longfellow based the poem on a story found in Timothy Alden’s 1814 book, A Collection of American Epitaphs. Timothy was also a descendant.

- The Timeline: Longfellow squashes several years of events into a few months. In reality, the marriage likely happened around 1622 or 1623.

- The Rivalry: There is no surviving contemporary record from the 1620s—like a diary or a letter—that mentions Miles Standish being angry at John Alden over a girl. In fact, they remained close neighbors and business partners for decades.

It’s kinda fascinating that the "feud" might be entirely made up. Yet, the image of the jilted Captain Standish storming off to fight in the Indian Wars while John and Priscilla pine for each other is what stuck in the American consciousness.

The Darker Side of the Story

We can’t talk about The Courtship of Miles Standish without mentioning how it treats the Native Americans. Longfellow writes from a 19th-century perspective, which means the portrayal of the local tribes is often stereotypical and "othered."

He depicts Standish as a protector, but also as someone with a hair-trigger temper. In one famous scene, Standish hangs the head of a Native American leader on the roof of the fort. Longfellow includes this to show Standish’s "bravery," but for modern readers, it’s a grim reminder of the violent reality of colonization that the romantic plot tries to soften.

Longfellow’s Secret Weapon: The Hexameter

If you try to read the book today, you’ll notice a weird, rolling rhythm. Longfellow used dactylic hexameter—the same meter used in Homer’s Iliad.

✨ Don't miss: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

It’s a bold choice. It makes the story feel "epic," like a Greek myth set in the woods of Massachusetts. Some critics at the time hated it. They thought it sounded like a galloping horse. But for the general public, it made the poem incredibly easy to memorize and recite at Thanksgiving dinners.

How to Read it Today

If you’re picking up a copy of The Courtship of Miles Standish for the first time, don't treat it like a history textbook. Treat it like a window into the 1850s. It tells us more about what Victorians wanted to believe about their ancestors than what actually happened in 1621.

You’ve got to appreciate the "domestic comedy" of it all. It’s surprisingly funny in parts, especially when Standish is bragging about his copy of Caesar’s Commentaries or when John is trying to find an excuse to stay in Plymouth instead of boarding the Mayflower back to England.

Actionable Insights for Literature Lovers:

- Visit the Sites: If you're in New England, you can actually visit the Alden House Historic Site in Duxbury. Seeing the actual land where John and Priscilla lived makes the poem feel much more grounded.

- Compare the "Big Three": To get the full Longfellow experience, read this alongside Evangeline and The Song of Hiawatha. You'll see how he was trying to build a "mythology" for a young America.

- Check the Genealogy: Because John and Priscilla had ten kids, millions of Americans are their descendants (including Marilyn Monroe and Orson Welles!). If you've done a DNA test, check your tree—you might be part of the story.

- Focus on the Verse: Don't just skim the words. Read a few stanzas out loud. The rhythm is designed for the ear, not just the eye. It’s meant to be a performance.