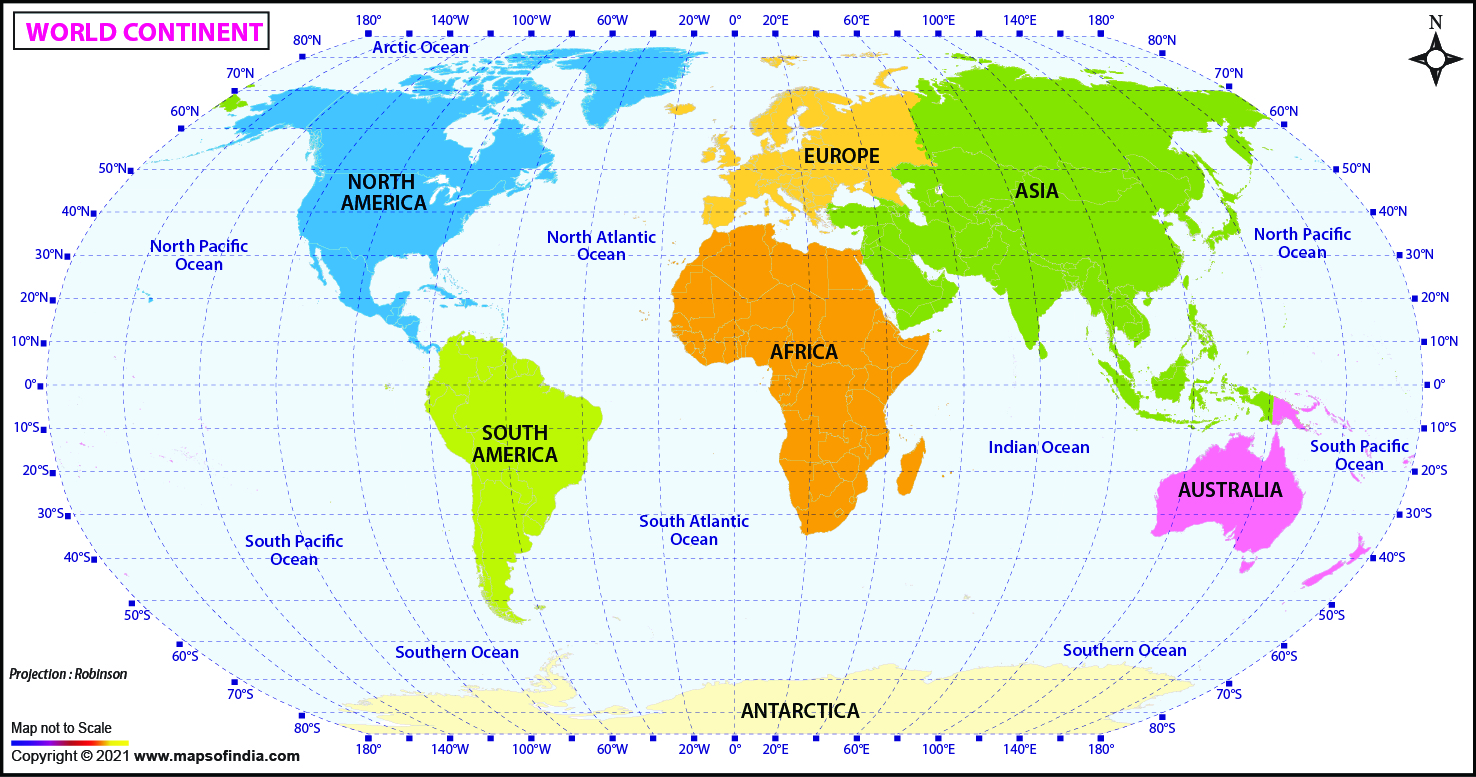

You probably remember that colorful poster hanging on your third-grade classroom wall. It showed seven distinct blobs of land, neatly separated by vast blue oceans, making the continents of the world map look like a finished jigsaw puzzle. Simple, right? Well, honestly, it’s a mess. Geographers, geologists, and politicians have been arguing for centuries about where one continent ends and another begins, or if "seven" is even the right number to use.

Geography isn't static. It's messy.

If you ask a student in London how many continents there are, they’ll say seven. Ask a student in Bogota, and they’ll likely tell you there are six, because they view North and South America as a single, massive landmass. Then you have the geologists. These folks look at tectonic plates rather than lines on a map. From their perspective, Europe and Asia are just one giant slab of rock called Eurasia.

The Seven-Continent Model is Basically a Suggestion

Most of us in the English-speaking world are taught the seven-continent model: Africa, Antarctica, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America. But this isn't a scientific law. It's a convention.

Take Europe and Asia. There is no ocean between them. If you’re standing in the Ural Mountains in Russia, you could technically have one foot in Europe and one in Asia. It’s a purely cultural and historical divide. Early Greek geographers like Hecataeus of Miletus originally split the world into three parts—Europe, Asia, and Libya (Africa)—based on the Mediterranean Sea. We’ve just kept that vibe going for over two thousand years because it's convenient for history books, not because the Earth’s crust says so.

Why South America and North America Aren't Always Separate

In much of Latin America and parts of Europe, the continents of the world map include a single "America." This isn't just a linguistic quirk. Geographically, the two are joined by the Isthmus of Panama. It wasn't until the Panama Canal was dug in 1914 that there was any physical separation at all. Even now, calling them two continents is more about political identity than physical geography.

The Weird Case of Zealandia

If you think the map is settled, think again. In 2017, a group of eleven geologists published a paper in GSA Today arguing for the recognition of a eighth continent: Zealandia. It’s a massive 4.9 million square kilometer piece of continental crust that is 94% underwater. New Zealand is just the highest tip of it. According to Nick Mortimer, a leading geologist on the project, Zealandia meets all the criteria—elevation, geology, and crustal structure—to be its own thing. It just happens to be mostly drowned.

Breaking Down the Landmasses: What’s Actually There?

Let’s look at the heavy hitters. Asia is the undisputed king of the continents of the world map. It covers about 30% of the Earth's total land area and holds 60% of the human population. You've got the highest point on Earth (Mount Everest) and the lowest point on land (the Dead Sea). It's so big that it contains almost every climate imaginable, from the freezing Siberian tundra to the tropical jungles of Indonesia.

Africa is the second-largest. It’s also the most central. It’s the only continent that spans both the northern and southern temperate zones. People often underestimate just how massive Africa is because of the Mercator projection—the way we usually flatten the globe onto a rectangular map. That projection makes Greenland look roughly the same size as Africa. In reality? Africa is fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit the USA, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa’s borders and still have room for change.

The Ice Kingdom

Antarctica is the odd one out. No permanent residents, no countries, and 98% of it is covered in ice. It’s technically a desert because it gets so little precipitation. If all that ice melted, the sea level would rise by about 60 meters. Scientists at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station live there in shifts, studying everything from climate change to astrophysics. It’s the only place on Earth where you can walk through every time zone in a few seconds just by circling the pole.

Australia or Oceania?

This is a common point of confusion. Is Australia a continent or an island? It’s both. But when people talk about the continents of the world map in a geopolitical sense, they often use the term "Oceania" to include New Zealand, Fiji, and the thousands of islands scattered across the Pacific.

Strictly speaking, the continent is Australia (or Sahul), which includes the mainland, Tasmania, and New Guinea. They sit on the same continental shelf.

North America’s Massive Reach

North America isn't just the US, Canada, and Mexico. It includes every island in the Caribbean and even Greenland. It’s the only continent that has every kind of climate: the ice cap of Greenland, the savanna of Central America, the tropical rainforest of Belize, and the desert of the Mojave. It’s geologically very stable, dominated by the Canadian Shield—some of the oldest rock on the planet, dating back over 4 billion years.

The Tectonic Reality

If you want to get really technical, the continents of the world map are just the parts of the tectonic plates that happen to be above sea level. The Earth is like a cracked eggshell. These plates move.

- The African Plate is slowly splitting in two. The East African Rift is literally pulling the continent apart. Millions of years from now, a new ocean will form there, and a chunk of East Africa will drift away.

- The Indian Plate is slamming into the Eurasian Plate. This slow-motion car crash is what pushed up the Himalayas. They’re still growing by about an inch every year.

- The Pacific Plate is mostly oceanic, but it’s the reason the "Ring of Fire" exists, causing the earthquakes and volcanoes that define the edges of Asia and the Americas.

Maps Lie to You (And That’s Okay)

We have to talk about the Mercator projection again. It was designed in 1569 for sailors. It’s great for navigation because a straight line on the map is a constant compass bearing. But it distorts size like crazy as you move away from the equator.

👉 See also: Why the Château Ramezay Museum Montreal Still Matters (And What You’re Likely Missing)

Africa and South America look way smaller than they are.

Europe and North America look way bigger.

The Gall-Peters projection is an alternative that shows the correct relative sizes of the landmasses, but it makes the shapes look "stretched" and weird to our eyes. Then there’s the Robinson projection, which is a compromise between shape and size. Most modern world maps you see in National Geographic use something like the Winkel Tripel projection to minimize distortion. There is no perfect way to wrap a sphere around a flat piece of paper.

Why This Matters for Travel and Life

Understanding the continents of the world map isn't just for trivia night. It changes how you see the world. When you realize that Europe is basically a large peninsula sticking off the side of Asia, it changes your perspective on history and trade. When you see how close South America and Africa look like they could fit together, you’re seeing the ghost of Gondwana—the supercontinent that existed 180 million years ago.

Actionable Takeaways for the Curious Mind

- Check out an AuthaGraph Map. It’s arguably the most accurate flat map ever made. It maintains the proportions of land and water while being able to be tiled in any direction. It’ll break your brain a little bit, but in a good way.

- Explore the "Micro-Continents." Look up places like Kerguelen Plateau or the Mascarene Plateau. These are "sunken" continental fragments that show the Earth’s map is way more complex than just seven shapes.

- Question the Borders. Next time you look at a map, look at the "borders" between continents. Look at the Sinai Peninsula (between Africa and Asia) or the Turkish Straits (between Europe and Asia). These narrow strips of land or water have shaped human conflict and commerce for millennia.

- Use the Right Projection. If you’re teaching kids or planning a long-haul trip, use a globe. Digital tools like Google Earth are great, but a physical globe is the only way to truly see the scale of the Pacific Ocean—which is so big it can fit all the continents inside it with room to spare.

The world isn't a static drawing. It's a moving, breathing system of plates and shifting definitions. The seven-continent model is a useful shorthand, but it's far from the whole story.