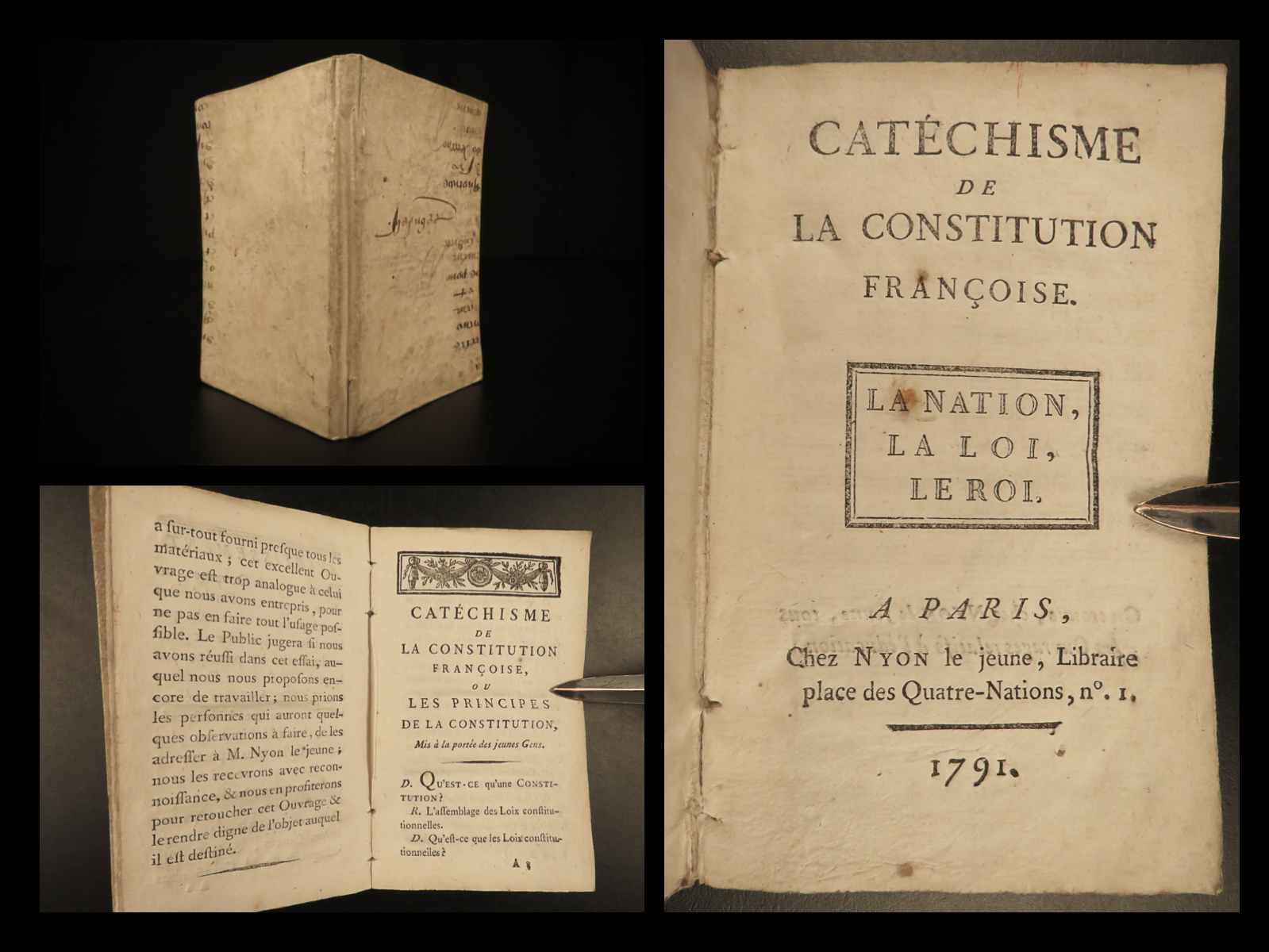

Honestly, if you want to understand why modern politics is such a mess, you have to look at the constitution of 1791 french revolution. It was a disaster. But it was a beautiful, ambitious, totally-doomed-from-the-start kind of disaster.

Think about it. You have a king, Louis XVI, who basically thinks he’s been hand-picked by God to run the show. Then you have a bunch of lawyers, intellectuals, and fed-up commoners—the National Assembly—who decide that, actually, the "people" should be in charge. The result was a document that tried to keep both sides happy and ended up pissing off literally everyone.

It didn't last. In fact, it barely survived a year. But the constitution of 1791 french revolution is where we get the "Left" and "Right" in politics. It’s where we first saw a country try to pivot from a total monarchy to a representative democracy without a roadmap.

The Messy Reality of a Constitutional Monarchy

By the time 1791 rolled around, France was already on fire. Not literally (well, sometimes literally), but the old system was dead. The National Assembly had been working on this document for two years. Two years of arguing in drafty halls while the price of bread skyrocketed and people were starving in the streets of Paris.

They finally finished it in September 1791.

The big idea? A constitutional monarchy.

Basically, Louis XVI got to keep his head and his throne, but he didn't have absolute power anymore. He was the "King of the French" now, not the "King of France." That’s a massive distinction. It meant he was a public servant, not the owner of the country.

💡 You might also like: Why the Corded DeWALT Circular Saw Still Wins on the Jobsite

But there was a catch. Actually, several catches.

The Assembly gave Louis a "suspensive veto." This meant he could delay laws he didn't like for up to four years. Imagine trying to run a revolution where the guy you’re revolting against can just hit the "pause" button on your laws for nearly half a decade. It was a recipe for gridlock.

Active vs. Passive Citizens (The Part Nobody Likes)

Here is where the constitution of 1791 french revolution really started to alienate the common people. Even though the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen said everyone was equal, the Constitution created two tiers of people.

- Active Citizens: Men over 25 who paid a certain amount of taxes (roughly the value of three days of labor). They could vote.

- Passive Citizens: Everyone else. Poor people, domestic servants, and, of course, all women. They had rights, but no vote.

Olympe de Gouges, a playwright and activist at the time, saw right through this. She wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791 because she knew the new constitution was leaving half the population behind. If you were a sans-culotte—the working-class radicals of Paris—you felt betrayed. You fought for the revolution, but the lawyers in the Assembly basically told you that you weren't "rich enough" to participate in it.

Why the Constitution of 1791 French Revolution Failed So Fast

You can’t talk about this period without mentioning the Flight to Varennes.

In June 1791, before the constitution was even finished, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette tried to bolt. They dressed up as servants and tried to escape to the border to meet up with an Austrian army. They got caught.

This changed everything.

Suddenly, the National Assembly was trying to finalize a constitution that relied on a king who had just tried to abandon his people. It’s like trying to finish a marriage contract after your spouse was caught packing their bags in the middle of the night.

The Assembly tried to cover it up. They claimed the King was "kidnapped." Nobody bought it.

The Legislative Assembly Chaos

When the constitution of 1791 french revolution finally went into effect, it created a new body called the Legislative Assembly. Because of a "Self-Denying Ordinance" proposed by Robespierre, none of the original members of the National Assembly could sit in the new one.

So, you had a brand-new government filled with people who had no experience.

These guys were divided. On one side, you had the Feuillants, who wanted the constitutional monarchy to work. On the other, you had the Jacobins and Girondins, who were getting increasingly radical.

And then there was the war.

In April 1792, France declared war on Austria. Why? Because the revolutionaries thought it would spread their ideas, and the King thought a war would lead to a French defeat that would put him back in power. It was a mess. When the war went badly, the people blamed the King (rightly so, he was rooting for the enemy).

By August 10, 1792, a mob stormed the Tuileries Palace. They suspended the King, and the Constitution of 1791 was officially dead.

The Experts Weigh In: Was it Ever Going to Work?

Historians have been arguing about this for centuries. Timothy Tackett, a leading scholar on the Revolution, argues in Becoming a Revolutionary that the members of the Assembly were actually quite talented, but they were trapped by their own idealism.

✨ Don't miss: Turkey Ethnic Groups Map: What Most People Get Wrong

Then you have someone like François Furet, who suggested that the Revolution was "drifting" toward violence from the start because the political culture was so polarized.

The reality is probably somewhere in the middle. The constitution of 1791 french revolution tried to bridge two worlds that were fundamentally incompatible: the world of divine right and the world of popular sovereignty.

It also ignored the economic reality. You can't tell a hungry person that they have "liberty" when they can't afford a loaf of bread and aren't allowed to vote for the person who sets the price of that bread.

Key Features of the 1791 Framework

- Unicameralism: There was only one house of the legislature. No "Senate" to slow things down, which made for very volatile lawmaking.

- Judicial Reform: It completely overhauled the courts, making judges elected rather than people who bought their offices.

- Administrative Change: It divided France into 83 departments, most of which still exist today. This was actually one of its most successful parts.

- Church Control: The Civil Constitution of the Clergy made priests state employees. This turned many devout Catholics against the revolution.

Actionable Takeaways from the 1791 Disaster

We often look at history as a bunch of dates, but the constitution of 1791 french revolution offers some pretty sharp lessons for today.

First, half-measures often satisfy no one. By trying to keep the King while stripping his power, the Assembly created a figurehead who became a magnet for counter-revolutionary plotting.

Second, political exclusion is a ticking time bomb. When you tell a large group of people—like the "passive citizens"—that they are part of a nation but have no say in its direction, they will eventually find a way to make their voices heard. Usually through a riot.

If you're looking to dive deeper into this specific moment, there are a few things you can do to get a better handle on the nuance.

👉 See also: Nail art on acrylic nails: What your tech probably isn't telling you

- Read the primary source: Look up the "Constitution of 1791" text. It’s surprisingly readable. Notice how much time they spend on the King's salary versus civil rights.

- Study the "Flight to Varennes": Check out Timothy Tackett’s book When the King Took Flight. It reads like a thriller and explains why this one event doomed the constitution.

- Map the Departments: Look at a map of France from 1789 versus 1791. The administrative cleanup was arguably the only part of this constitution that actually worked and lasted.

- Analyze the Veto Power: Compare the "suspensive veto" of 1791 to the presidential veto in the U.S. Constitution. It shows you how much the French were trying to avoid "American-style" executive power.

The constitution of 1791 french revolution was a bridge. It didn't hold the weight of the country, and it collapsed into the Terror that followed. But without it, we wouldn't have the modern concepts of citizenship and secular governance that we take for granted now. It was a failure, sure. But it was a failure that changed the world.