It was hot. Ridiculously hot. On August 1, 1971, Madison Square Garden wasn't just a basketball arena; it was a pressure cooker of rock and roll history and humanitarian desperation. George Harrison was terrified. He hadn't played a proper live show since the Beatles quit touring years earlier, and now he was trying to save a country. When we talk about the concert for bangladesh songs, we aren't just talking about a setlist. We’re talking about the moment the "Quiet Beatle" became a leader, dragging his famous friends—some willingly, some through a haze of nerves—into the first-ever mega-charity event.

Most people remember the hits. They remember "While My Guitar Gently Weeps." But if you look at the raw footage, the real story is in the grit. It’s in the way Ravi Shankar opened the show by asking the audience to stop smoking pot because the sitar is a sacred instrument. It’s in the way Bob Dylan showed up at the last second, despite George not being sure he’d actually walk onto the stage.

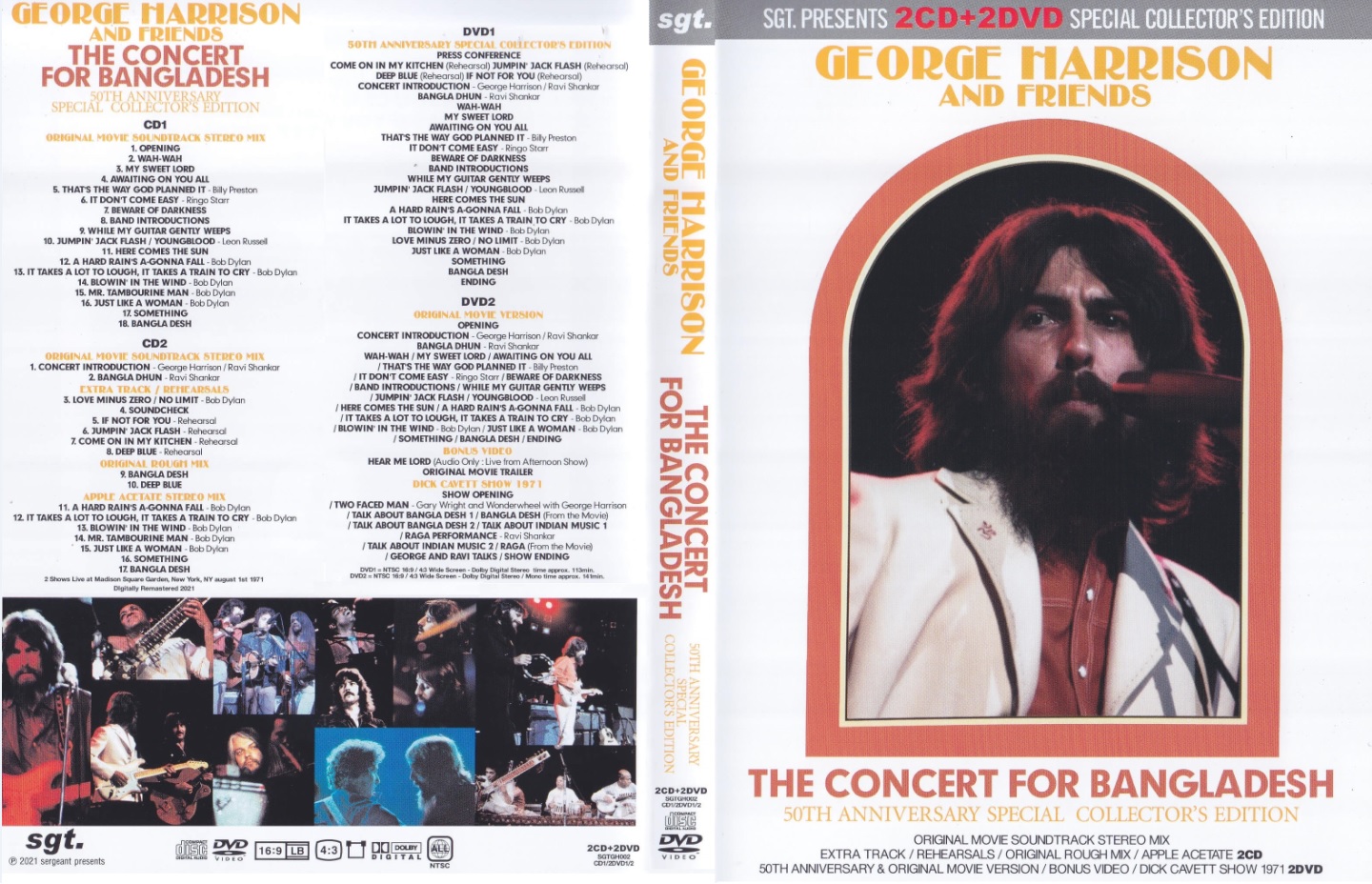

The Setlist That Defined a Generation

The afternoon and evening shows followed a similar trajectory, but they felt worlds apart. George started things off with "Wah-Wah." Honestly, it’s one of the best versions of that track ever recorded. You can hear the resentment toward his former bandmates in those guitar lines, but here, it was transformed into a wall of sound that filled the Garden. It set the tone. This wasn't a "peace and love" hippie fest in the vein of Woodstock; it was professional, urgent, and heavy.

Then you had Billy Preston. If you haven't watched the video of him performing "That's the Way God Planned It," you're missing out on pure kinetic energy. He literally gets up from his organ and starts dancing across the stage, and for a second, you forget the tragedy in South Asia. You just feel the soul.

Why Ravi Shankar’s Opening Mattered

Before the rock stars took over, there was the "Bangla Dhun." It lasted nearly 20 minutes. For a New York crowd used to three-minute pop singles, this was a massive risk. Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan weren't just playing background music. They were trying to translate the suffering of millions into melody.

Funny enough, the crowd cheered after they finished tuning their instruments. Shankar famously joked, "If you appreciate the tuning so much, I hope you will enjoy the music more." It was a light moment in a heavy day. But the music that followed—that frantic, rhythmic interplay—demanded respect. It forced the Western ear to listen to the East, which was the entire point of the fundraiser.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

The Dylan Factor: A Surprise Shift in Energy

Let’s talk about the Bob Dylan set. This was a huge deal. Dylan had been largely reclusive since his 1966 motorcycle accident, and no one—not even George—knew if he’d actually play. When he walked out with his acoustic guitar and harmonica, the room shifted.

He played five songs:

- "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall"

- "It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry"

- "Blowin' in the Wind"

- "Mr. Tambourine Man"

- "Just Like a Woman"

His voice was clear. It wasn't the gravelly rasp of later years. It was sharp. When he sang "A Hard Rain," the lyrics about "blue-eyed sons" and "starved populations" hit differently because of why they were there. It wasn't a protest song from the 60s anymore; it was a description of the evening news. Leon Russell was back there on bass, and Ringo Starr was banging a tambourine like his life depended on it. It was loose. It was real.

The Logistics of the Concert for Bangladesh Songs

Pulling these tracks off live was a technical nightmare. Phil Spector was involved in the recording, which meant everything was being captured for a triple-album release. You had two drummers—Ringo and Jim Keltner—playing simultaneously. You had a horn section. You had a massive choir of backing singers.

Harrison’s "Awaiting on You All" is a great example of this. It’s a dense track. On the All Things Must Pass album, it’s layered with Spector’s "Wall of Sound" production. Recreating that in 1971 without modern digital tech was a feat of engineering. They did it through sheer volume and a lot of rehearsal time at Nola Studios.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Leon Russell’s Show-Stealing Medley

If George was the heart of the show, Leon Russell was the fire. His medley of "Jumpin' Jack Flash" and "Young Blood" is probably the most aggressive moment in the entire concert. He was a force of nature with that long hair and those pounding piano keys. He took a Rolling Stones classic and made it sound like a gospel revival. It’s often cited by critics as the highlight of the night, even though it wasn't a "Beatle" moment. It provided the necessary high-octane contrast to George’s more spiritual, mid-tempo tracks like "My Sweet Lord."

The Tragedy Behind the Triumph

We can't talk about the concert for bangladesh songs without talking about the money. Or the lack of it, at first. George famously wrote the song "Bangla Desh" specifically to raise awareness. It’s a literal plea: "My friend came to me with sadness in his eyes / He told me that he wanted help before his country dies."

The song was released as a single just before the show. It’s not a poetic masterpiece, but it’s an effective one. It’s journalism set to music. However, the tragedy continued after the final note. Because of tax issues and the way the funds were handled through Apple Corps, millions of dollars were tied up in escrow for years. The IRS wanted their cut. It was a mess. George was devastated by the bureaucracy. He just wanted to feed people.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think this was a Beatles reunion that didn't happen. It wasn't. Paul McCartney declined because he felt it was too soon after the legal battles of the band's breakup. John Lennon was supposed to be there, but George didn't want Yoko Ono on stage, so John backed out at the eleventh hour.

This made the presence of Ringo and George together even more poignant. When they played "Something," it felt like a goodbye to the 60s. It was George’s crowning achievement as a songwriter, performed with his "big brother" Ringo on the drums, but without the baggage of the Fab Four. It was the first time a Beatle had stood on a stage as a solo entity and commanded that kind of authority for a cause greater than the music itself.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

The Enduring Impact of the Setlist

So, why does this specific group of songs still matter? It’s because it created the template. Without "Just Like a Woman" or "Beware of Darkness" being played that night, we don't get Live Aid. We don't get Farm Aid. We don't get the idea that a rock star has a moral obligation to use their platform for geopolitical intervention.

The performances were raw. You can hear George’s voice crack occasionally. You can hear the feedback. But that’s the point. It was human. It was an emergency.

If you're looking to dive into this era of music, don't just stream the hits. Find the original 1971 film. Watch the way the musicians look at each other. There’s a moment during "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" where Eric Clapton and George Harrison are trading lines. Clapton was struggling with serious personal demons at the time—he’d barely been out of his house in months—and George dragged him onto that stage to save him, too.

Actionable Ways to Experience This History

If you want to truly appreciate the depth of these performances, follow these steps:

- Listen to the 2005 Remaster: The original vinyl was great, but the 2005 digital remaster cleaned up the muddy bottom end. You can finally hear Klaus Voormann’s bass lines clearly.

- Watch the Documentary Footage: Pay attention to the "Electronic Press Kit" or the "Making of" features. It shows the frantic rehearsals and the sheer scale of the 44-musician ensemble.

- Compare the Afternoon and Evening Shows: Some versions of the album swap tracks between the two performances. Dylan’s energy is markedly different between the two sets; he’s more confident in the second.

- Read "I Me Mine": George Harrison’s autobiography gives a glimpse into his mindset during the planning. He didn't want to be the "leader," but he realized no one else was going to do it.

- Support the George Harrison Fund for UNICEF: The legacy of the concert lives on. The money from sales of the album and DVD still goes to help children in need via UNICEF.

The concert for bangladesh songs weren't just about melody or rhythm. They were a bridge between the ego-driven rock of the late 60s and the socially conscious activism of the future. When the final notes of the song "Bangla Desh" faded out, the audience didn't just leave a concert. They left a moment where the world actually felt small enough to fix.

The music holds up because it was born out of necessity. It wasn't a tour stop. It was a one-night-only stand against apathy. And that's something you can still hear in every chord.