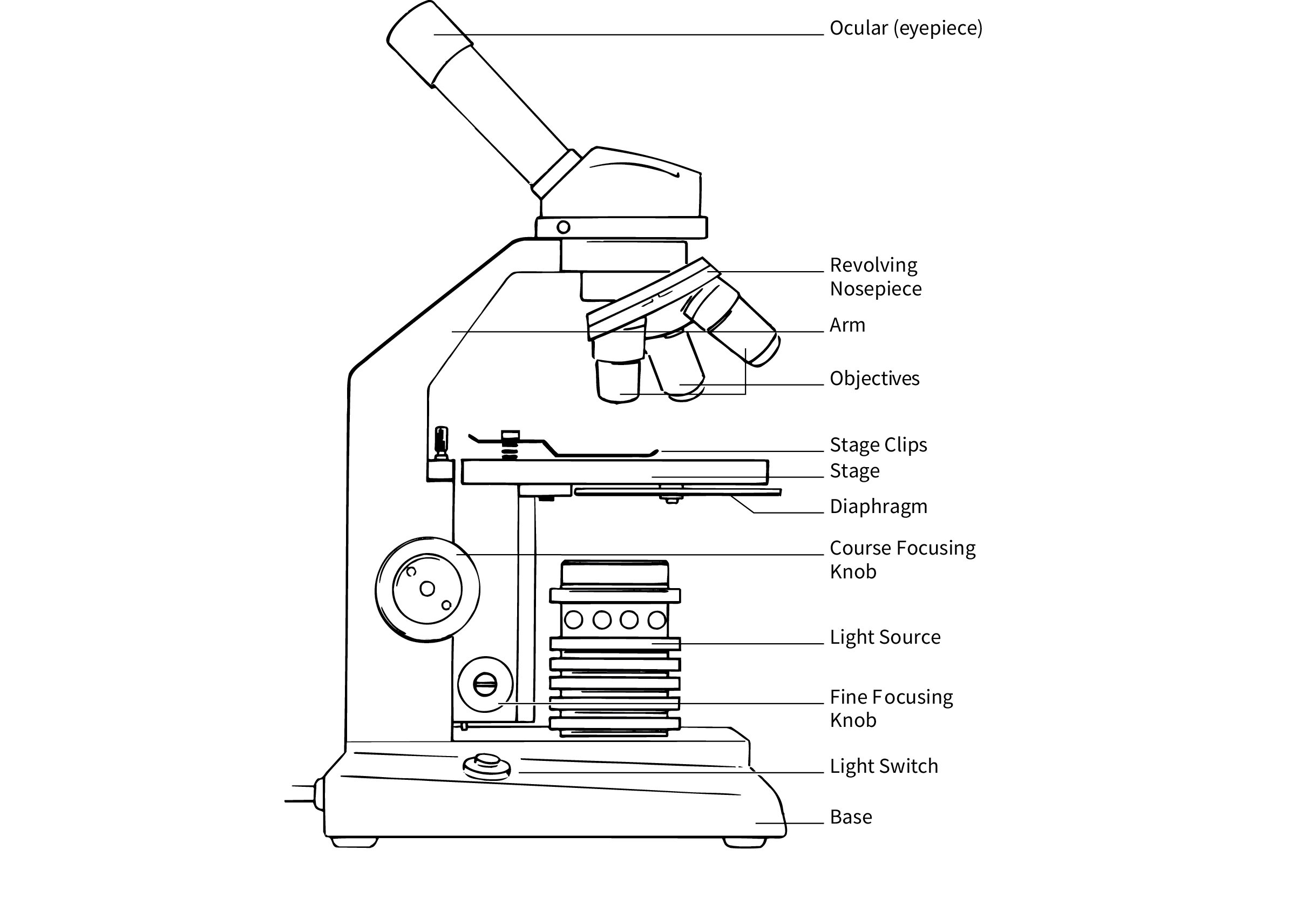

You probably remember the smell of floor wax and old slides from high school biology. You’re staring at a heavy metal instrument, trying not to squint too hard, while a diagram of a compound microscope sits propped up in a textbook next to you. It looks simple enough on paper. A few lines pointing to a lens here and a knob there.

But honestly? Most people get the physics of this thing completely backwards.

A compound microscope isn't just a magnifying glass on a stand. It’s a sophisticated two-stage light-bending machine. If you don't understand how the objective lens interacts with the eyepiece, you’re basically just looking at blurry blobs of light. We’re going to tear down the standard diagram and look at what’s actually happening inside that brass or plastic tube.

The Optical Path is Where the Magic Happens

Most diagrams start with the "arm" or the "base." That's boring. That’s just the skeleton. The soul of the machine is the optical train.

Think about the light. It starts at the illuminator at the bottom. It doesn't just "shine." It has to be harnessed. This is where the condenser comes in. If your diagram doesn't emphasize the condenser and the iris diaphragm, it's a bad diagram. These components don't magnify; they shape the light into a cone that matches the aperture of your objective lens.

The Objective Lens: The Real MVP

This is the most important part of any compound microscope. Period. Most scopes have three or four objectives mounted on a revolving nosepiece. You’ve got your 4x (scanning), 10x (low power), 40x (high power), and maybe a 100x oil immersion lens.

Here is what’s wild: the objective lens creates a real, inverted, and enlarged image inside the body tube.

Wait. Did you catch that?

💡 You might also like: Heavy Aircraft Integrated Avionics: Why the Cockpit is Becoming a Giant Smartphone

The image isn't "in" the slide anymore. It’s floating in mid-air inside the microscope. This is called the intermediate image. If you were to stick a piece of frosted glass inside the tube at the right spot, you’d actually see the specimen projected onto it.

The Ocular Lens (Eyepiece)

Now, the eyepiece—or ocular—takes that floating intermediate image and magnifies it again. This second magnification creates a virtual image. This is what your eye actually sees. It’s "virtual" because the light rays don't actually converge where the image appears to be; your brain just traces them back and perceives a giant version of the cell or bacteria.

Total magnification is simple math, but people still mess it up. You multiply the power of the objective by the power of the ocular. Usually, that’s $10x \times 40x = 400x$.

Mechanical Parts: More Than Just Metal

If the lenses are the eyes, the mechanical parts are the muscles. A diagram of a compound microscope usually labels the stage, the coarse adjustment knob, and the fine adjustment knob.

But there’s a nuance here that experts know.

The coarse adjustment should only be used with the lowest power objective. If you’re using the 40x or 100x lens and you start cranking that big coarse knob, you’re going to hear a very expensive crunch. That’s the sound of a glass slide shattering against a precision lens.

The Mechanical Stage

On cheaper models, you just have two metal clips. They’re annoying. You have to nudge the slide with your fingers, which is like trying to do surgery with oven mitts. Professional diagrams show a mechanical stage with two knobs (X and Y axis). This allows for sub-millimeter precision. When you’re looking at a paramecium zooming across the field of view at 400x, you need that precision to keep it in frame.

📖 Related: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

Common Misconceptions in Most Diagrams

Diagrams often fail to explain Numerical Aperture (NA). You’ll see a number like "0.65" etched into the side of the 40x objective.

What does it mean?

It’s not magnification. It’s the lens’s ability to gather light and resolve fine detail. A lens with a higher NA can see two tiny points as separate objects rather than one blurry smear. This is the "resolution" of the microscope. Magnification without resolution is "empty magnification"—it’s like blowing up a low-res JPEG. It gets bigger, but it doesn't get clearer.

Another thing? The diaphragm.

People think the diaphragm is for controlling brightness. It’s not. Use the rheostat (the light dimmer) for brightness. The diaphragm is for contrast. If you’re looking at unstained cheek cells, they’re almost transparent. If you blast them with light, you won't see a thing. You have to close the diaphragm to create shadows and depth.

The Physics of Oil Immersion

When you get to the 100x objective, things change. You’ll notice a "100x Oil" label on the lens in any decent diagram.

Why oil?

👉 See also: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

Physics is a jerk. When light travels from glass into air, it bends (refraction). At very high magnifications, that light bends so much it actually misses the tiny opening of the objective lens. By placing a drop of immersion oil between the slide and the lens, you create a continuous path. The oil has the same refractive index as glass. The light doesn't bend; it goes straight into the lens.

Without that oil, the 100x lens is basically useless. It’ll just look like you’re staring through a bucket of milk.

How to Actually Use This Knowledge

If you’re a student, a hobbyist, or just someone who bought a scope on eBay because it looked cool, here is the "pro" workflow that the diagram doesn't tell you:

- Start Low: Always start at 4x. Find your specimen. Center it.

- Focus Coarse: Get it sharp with the big knob.

- The Click: Rotate to 10x. You should only need the fine adjustment now. This is called being parfocal.

- Adjust the Light: Don't just turn it up. Move the condenser and play with the diaphragm. Watch how the details "pop" as you restrict the light.

- Center Again: Before you move to 40x, make sure what you want to see is dead center. The field of view gets much smaller as magnification goes up.

Why the Compound Microscope Still Rules

We have electron microscopes now that can see atoms. So why do we still care about a light microscope?

Because you can look at live things.

Electron microscopy requires a vacuum and usually coating the specimen in gold. That kills the cell. With a compound microscope, you can watch a white blood cell chase a bacterium in real-time. You can see the cytoplasmic streaming in an Elodea leaf. It’s a window into a living world that’s happening right under your nose.

Practical Troubleshooting

- Black circles? Your nosepiece isn't clicked into place.

- Dirty spots that move when you turn the eyepiece? Your ocular is dirty. Use lens paper, not your shirt.

- The image is bright but flat? Close your diaphragm.

- Can't find anything? Go back to 4x. Seriously. Everyone hates doing it, but it's the only way.

Next Steps for Mastering Microscopy

To move beyond just looking at a diagram of a compound microscope, you need hands-on practice with slide preparation.

- Learn the Wet Mount: Start by practicing the "wet mount" technique using a drop of pond water and a cover slip at a 45-degree angle to avoid air bubbles.

- Experiment with Stains: Buy some Methylene Blue or Iodine. Staining makes the nucleus of a cell visible, transforming a "clear blob" into a detailed map of life.

- Calibration: If you want to be a real pro, look into "Koehler Illumination." It’s a specific way of aligning the light path that provides the absolute highest quality image possible for your specific optics. Most people never do it, but it makes a world of difference.

Go grab a slide. Get some pond water. Stop looking at the diagram and start looking through the glass.