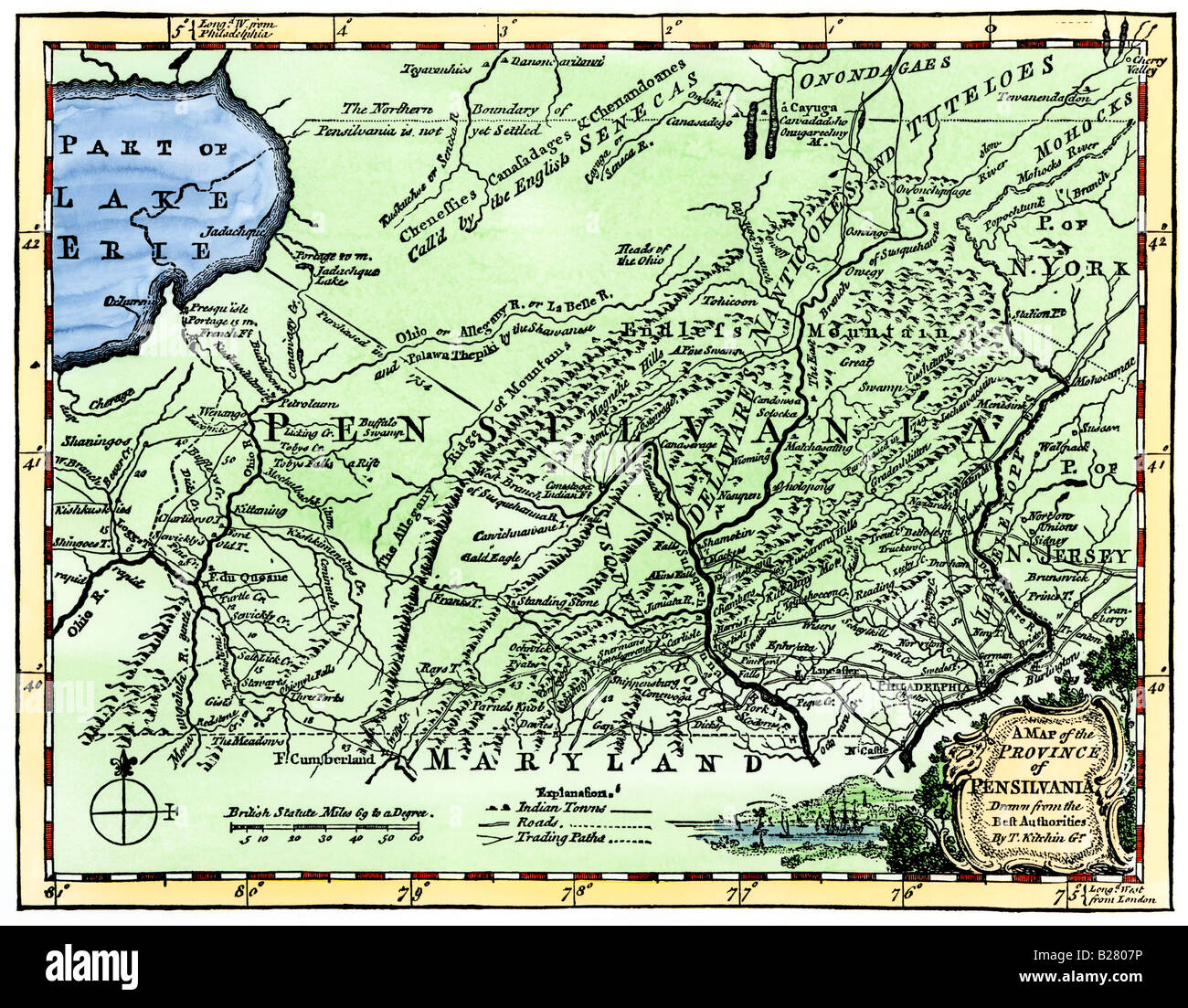

If you look at a modern map of the United States, Pennsylvania is a nice, tidy rectangle. It’s got that little chimney up in the northwest corner touching Lake Erie, but otherwise, it’s a geometric dream. However, if you stepped back into 1681 and looked at a colony of Pennsylvania map, you’d see a chaotic jigsaw puzzle of overlapping claims, vague descriptions, and enough legal drama to keep a courtroom busy for a century.

William Penn was given a massive chunk of land by King Charles II to settle a debt. Sounds simple. It wasn't.

The original charter basically said Penn owned everything between the 40th and 43rd degrees of latitude. Here’s the problem: nobody in the 17th century actually knew exactly where those lines were. Mapping was a mix of sketchy compass readings and "best guesses." This led to a series of border wars that almost turned the "Holy Experiment" into a full-blown combat zone.

The Disputed Southern Border: The Mason-Dixon Nightmare

The most famous part of any colony of Pennsylvania map is the bottom line. Most people assume the Mason-Dixon line was always there. It wasn't. For decades, the Penn family and the Calvert family (who owned Maryland) were at each other's throats.

The Calverts claimed their land went up to the 40th parallel. The Penns claimed their land started at the 40th parallel. By modern measurements, the 40th parallel actually runs right through North Philadelphia. If the Calverts had won, Philadelphia—the crown jewel of the Quaker colony—would have been in Maryland. Penn, understandably, freaked out.

He argued that his land should start lower down, near the 39th degree, based on where the Delaware River bent. This wasn't just about dirt; it was about water access. Without the Delaware Bay, Pennsylvania was landlocked. To fix this, Penn actually convinced the Duke of York to give him the "Lower Counties," which we now call Delaware.

For a long time, the colony of Pennsylvania map actually included Delaware as a weird appendage. They shared a governor but eventually had separate legislatures. It was a messy, long-distance relationship that lasted until the Revolution.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Connecticut Thinks It Owns Scranton?

This is the part of the colony of Pennsylvania map history that usually gets left out of the textbooks. Because of some incredibly lazy wording in early royal charters, Connecticut claimed a huge strip of northern Pennsylvania.

Connecticut's charter said their land stretched "from sea to sea." They looked at a map, drew two horizontal lines across the continent, and realized that the Wyoming Valley (around modern-day Wilkes-Barre) fell right in their path.

Pennsylvanians weren't having it.

This led to the Pennamite-Yankee Wars. These weren't just legal disputes; people were actually shooting at each other over these farm plots. Settlers from Connecticut moved in, built forts, and fought Pennsylvania militias. It took the Articles of Confederation and a special court hearing in 1782 to finally tell Connecticut to stay in its own lane.

Walking the Land: The Infamous Walking Purchase

When you look at an early colony of Pennsylvania map, you see the territory slowly expanding westward and northward. That expansion wasn't always peaceful or honest.

Take the Walking Purchase of 1737.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

William Penn’s sons, Thomas and John, weren't quite the "Peaceable Kingdom" types their father was. They produced a likely forged deed from the 1680s claiming the Lenape had sold a tract of land as far as a man could walk in a day and a half. The Lenape figured a guy would walk maybe 20 or 30 miles.

The Penn brothers cheated.

They cleared a path, hired the fastest runners in the colony, and had them sprint. They covered about 64 miles. This effectively stole 1.2 million acres of prime timber and farmland. If you look at the colony of Pennsylvania map before and after 1737, you see a massive, jagged bite taken out of Lenape territory. It destroyed the relationship between the Quakers and the Native tribes, leading directly to the bloodshed of the French and Indian War.

The Western Frontier and the "Endless Mountains"

Mapping the western half of the colony was an exercise in frustration. The Appalachian Mountains—specifically the Alleghenies—acted as a massive physical barrier. On a 1750 colony of Pennsylvania map, the western third of the state is often just a blank space or labeled with generic terms like "The Endless Mountains."

Virginia also thought they owned Pittsburgh.

Governor Dunmore of Virginia actually established "District of West Augusta" in what is now Southwestern Pennsylvania. They even had a courthouse in what we now call Washington, PA. It wasn't until the 1780s that Pennsylvania and Virginia finally agreed to extend the Mason-Dixon line westward to create the "Panhandle" of West Virginia and fix Pennsylvania’s western edge.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

How to Read an Old Pennsylvania Map

If you’re looking at an authentic 18th-century map, like the famous 1770 William Scull map, you’ll notice a few things that look "wrong."

- The Spelling: You might see "Pensilvania" with one 'n'. Spelling was more of a vibe than a rule back then.

- County Lines: In 1682, there were only three: Philadelphia, Bucks, and Chester. Everything else was "unorganized."

- The "Waggon Roads": Early maps highlight the Great Wagon Road. This was the interstate of the 1700s, carrying settlers down through the Shenandoah Valley.

The colony of Pennsylvania map was a living document. It grew, shrank, and shifted based on who was winning a lawsuit or who had the fastest runners.

Actionable Steps for Map Enthusiasts and Researchers

If you want to track down the real history of these borders, don't just look at a modern recreation.

- Search the Pennsylvania State Archives: They hold the original "copia" of the 1681 Charter.

- Look for Nicholas Scull and William Scull maps: These were the "official" surveyors of the mid-1700s. Their maps show the actual locations of frontier forts and early Native American trails.

- Visit the Mason-Dixon Markers: You can still find the original limestone "crownstones" placed every five miles along the border. They have the Penn coat of arms on one side and the Calvert arms on the other.

- Check the "Holograph" Maps: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has hand-drawn sketches by early surveyors that show the "as-is" reality of the woods before the fancy engraved maps were printed in London.

Understanding the colony of Pennsylvania map is really about understanding how a wild, wooded frontier was slowly carved into a political entity through grit, shady deals, and some really impressive (and sometimes really bad) geometry.

Practical Insight: When researching 18th-century Pennsylvania genealogy or land grants, always check the neighboring state's archives too. Because the borders were so fluid, your ancestor's "Maryland" farm might actually be in Pennsylvania today, or vice versa. Always search by "watershed" or "creek name" rather than just the county, as county lines moved almost every decade as the population pushed west.