Imagine driving through the high desert of Idaho, surrounded by nothing but sagebrush and the distant, jagged teeth of the Lost River Range. You’re in the middle of the Idaho National Laboratory (INL)—formerly the National Reactor Testing Station—and you stumble upon a massive, windowless hunk of concrete. This isn't your typical office building. It’s the nuclear aircraft facility blockhouse, a relic from a time when the United States seriously thought it could fly bombers powered by nuclear fission. It sounds like something ripped straight out of a Fallout game, but the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program was a multi-billion dollar reality that nearly changed aviation forever.

The blockhouse wasn't built for aesthetics. It was built for survival. Specifically, the survival of the engineers and scientists who had to monitor live reactor tests from just a few hundred feet away.

Why a Nuclear Aircraft Facility Blockhouse Exists

The Cold War was weird. In the 1950s, the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission were obsessed with endurance. Jet fuel is heavy, and it runs out. But a nuclear-powered bomber? That could stay airborne for weeks, loitering near the Soviet border without ever needing to touch the ground. To make this happen, they built Test Area North (TAN). This site was the heart of the ANP program.

The nuclear aircraft facility blockhouse served as the nerve center for the Heat Transfer Reactor Experiments, known as HTRE-1, HTRE-2, and HTRE-3. If you’ve ever seen the photos of those massive, twin-jet engines strapped to a reactor core on a railroad car, that’s what was being controlled from inside this concrete shell.

The Shielding Logic

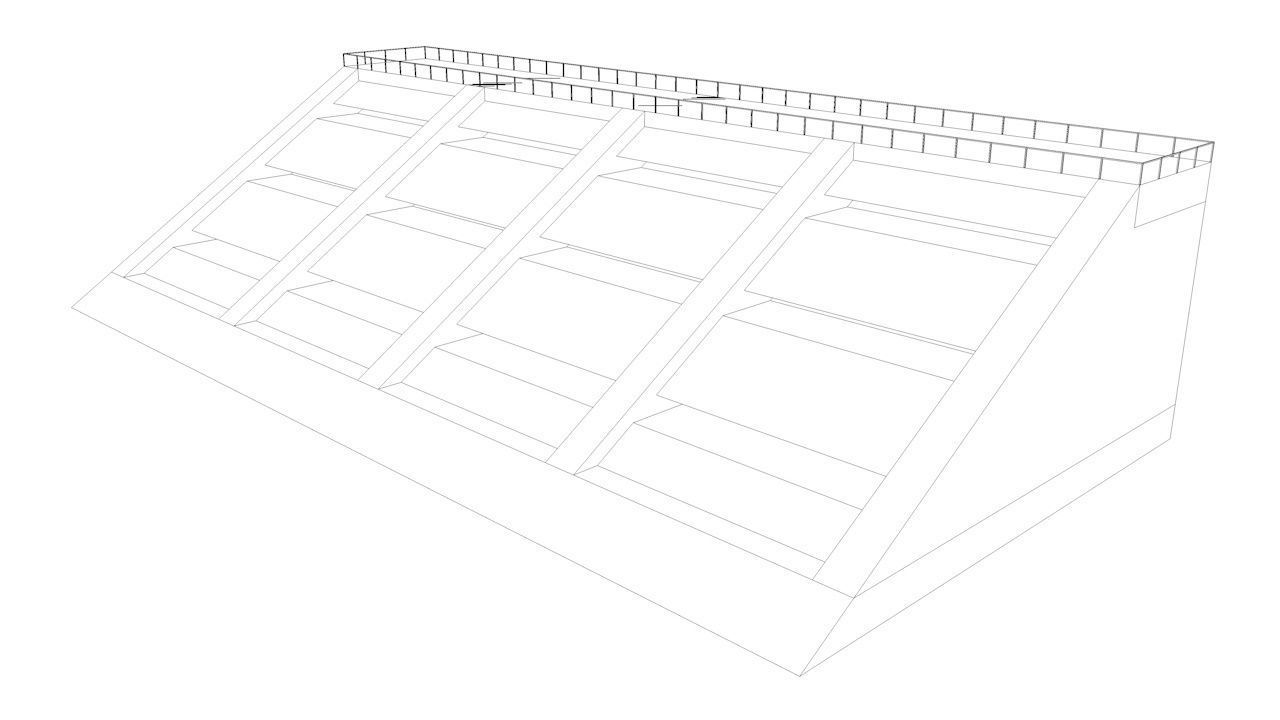

You can't just stand next to an unshielded nuclear reactor while it's running at full tilt to power a jet turbine. The blockhouse had walls made of reinforced concrete several feet thick. Some sections used high-density "heavy" concrete, which incorporated magnetite or barite to better soak up gamma radiation and neutrons. It had to be a fortress.

Life Inside the Bunker

Basically, the blockhouse was a high-tech cave. Inside, technicians sat at rows of analog dials, toggle switches, and oscilloscopes. They weren't looking through glass windows; they used periscopes and closed-circuit television—primitive by our standards, but cutting-edge for 1955—to watch the "Hot Shop."

✨ Don't miss: New DeWalt 20V Tools: What Most People Get Wrong

The Hot Shop was the nearby massive hangar where the actual radioactive work happened. It featured some of the largest remote-handling manipulators ever built. If a part on the nuclear engine broke, you couldn't send a mechanic in with a wrench. You had to do it via giant robotic arms from the safety of the blockhouse or the shielded gallery.

It was loud. It was tense. And honestly, it was a little bit terrifying.

One of the lead scientists on the project, Herbert York, later noted that the technical challenges were immense. You weren't just building a reactor; you were building a reactor that had to be light enough to fly but powerful enough to heat air to the point of thrust. That's a brutal engineering paradox.

The Engineering Behind the Madness

The nuclear aircraft facility blockhouse monitored two main types of cycles: the direct cycle and the indirect cycle.

- The Direct Cycle (GE's approach): This was the "dirty" one. Air was sucked into the intake, passed directly through the white-hot reactor core, and shot out the back. If the fuel elements leaked even a little, the exhaust became a radioactive trail.

- The Indirect Cycle (Pratt & Whitney's approach): This used a liquid metal coolant to transfer heat from the reactor to a heat exchanger, which then heated the air. It was cleaner but way more complex and prone to leaks.

Most of the testing at the Idaho facility focused on the GE direct cycle. The HTRE-3 experiment actually succeeded in powering two turbojet engines entirely with nuclear heat in 1959. For a brief moment, the dream was alive.

🔗 Read more: Memphis Doppler Weather Radar: Why Your App is Lying to You During Severe Storms

The Abandoned Giant

So why don't we have nuclear planes today? Well, the blockhouse holds the answer to that too. President John F. Kennedy officially pulled the plug on the ANP program in 1961.

By then, we had spent about $1 billion—which is roughly $10 billion in today's money. The reasons were simple but insurmountable:

- ICBMs became a thing, making long-range bombers less "essential."

- Shielding the crew required so much lead and water that the planes became absurdly heavy.

- If a nuclear plane crashed, you didn't just have a wreck; you had a localized environmental disaster.

Visiting the Site Today

You can’t just wander into the nuclear aircraft facility blockhouse for a weekend tour. Most of Test Area North has been decommissioned and demolished. However, the legacy remains at the EBR-1 (Experimental Breeder Reactor-I) Atomic Museum nearby.

While the original TAN blockhouse is largely inaccessible or stripped, the HTRE engines themselves—those massive, rusted, steampunk-looking contraptions—were moved to the EBR-1 parking lot. You can literally walk up to them. Seeing the size of the reactor vessels makes you realize why the blockhouse had to be so stout.

The scale of the hardware is haunting. You see the massive lead-shielded cabs where pilots were supposed to sit, looking like something out of a Jules Verne novel. It’s a testament to an era where we thought there was no problem that couldn't be solved with more split atoms.

💡 You might also like: LG UltraGear OLED 27GX700A: The 480Hz Speed King That Actually Makes Sense

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think these reactors actually flew. They didn't.

While a modified B-36 bomber (the NB-36H) did fly with a small reactor on board to test shielding, that reactor never actually powered the engines. The real "power" testing happened on the ground, tethered to the systems monitored by the blockhouse.

Another misconception? That the program was a total failure. It wasn't. The materials science developed at the nuclear aircraft facility blockhouse paved the way for high-temperature reactors used in other applications later. We learned how to manage liquid metals and how to build compact cores that could survive extreme vibration.

Actionable Insights for History and Tech Enthusiasts

If you're fascinated by the intersection of the Cold War and nuclear tech, there are a few things you should actually do rather than just reading about it:

- Visit the EBR-1 National Historic Landmark: Located on Highway 20/26 between Idaho Falls and Arco. It's seasonal (typically summer), so check the INL website before you drive out into the desert. You can see the HTRE engines there for free.

- Dig into the Digital Archives: The Idaho National Laboratory maintains a public reading room with declassified reports on the ANP program. Search for "Test Area North" and "HTRE" to see the original blueprints of the facility.

- Explore the "Atomic City" Vibe: Stop by the town of Atomic City, Idaho. It’s a semi-ghost town that once thrived on the business of the testing station. It gives you a visceral sense of the isolation these workers dealt with.

- Watch for Documentaries: Look for "The Nuclear Airplane" or similar archival footage from the 1950s. Seeing the "Hot Shop" in motion via old 16mm film puts the scale of the blockhouse's mission into perspective.

The era of the nuclear-powered bomber is over, but the concrete remains of the nuclear aircraft facility blockhouse stand as a monument to a time when we weren't afraid to try the impossible—even if the impossible was a terrible idea.