You’ve probably walked past a Co-op storefront a thousand times without really thinking about the massive, sprawling history behind it. It’s just a place to grab milk or a meal deal, right? Well, sort of. But if you dig into the roots of the Co operative Wholesale Society (CWS), you find something way more radical than a neighborhood grocery store. We’re talking about a group of working-class people in Northern England who, back in the 1860s, decided they were tired of being ripped off by middle-men and industrial fat cats. They didn't just want better flour; they wanted to own the whole damn supply chain.

Honestly, the CWS is the blueprint for every "disruptive" business model we see today, from Costco to REI. It was built on the idea that if you pool your resources, you can outmuscle the biggest monopolies. It wasn't always pretty—there were massive internal fights, near-bankruptcies, and a lot of messy bureaucracy—but the sheer scale of what they achieved is honestly mind-blowing. At one point, the CWS owned tea plantations in Sri Lanka, soap factories, and even its own fleet of steamships.

Where the Co operative Wholesale Society Actually Came From

People often get the CWS confused with the Rochdale Pioneers. The Pioneers were the ones who started the first successful retail co-op in 1844 on Toad Lane. But by the 1860s, these small individual shops realized they had a massive problem. While they were doing okay selling to their members, they were still at the mercy of private wholesalers who hated the co-operative movement. These wholesalers would often charge co-ops higher prices or sell them lower-quality goods just to see them fail.

In 1863, things changed.

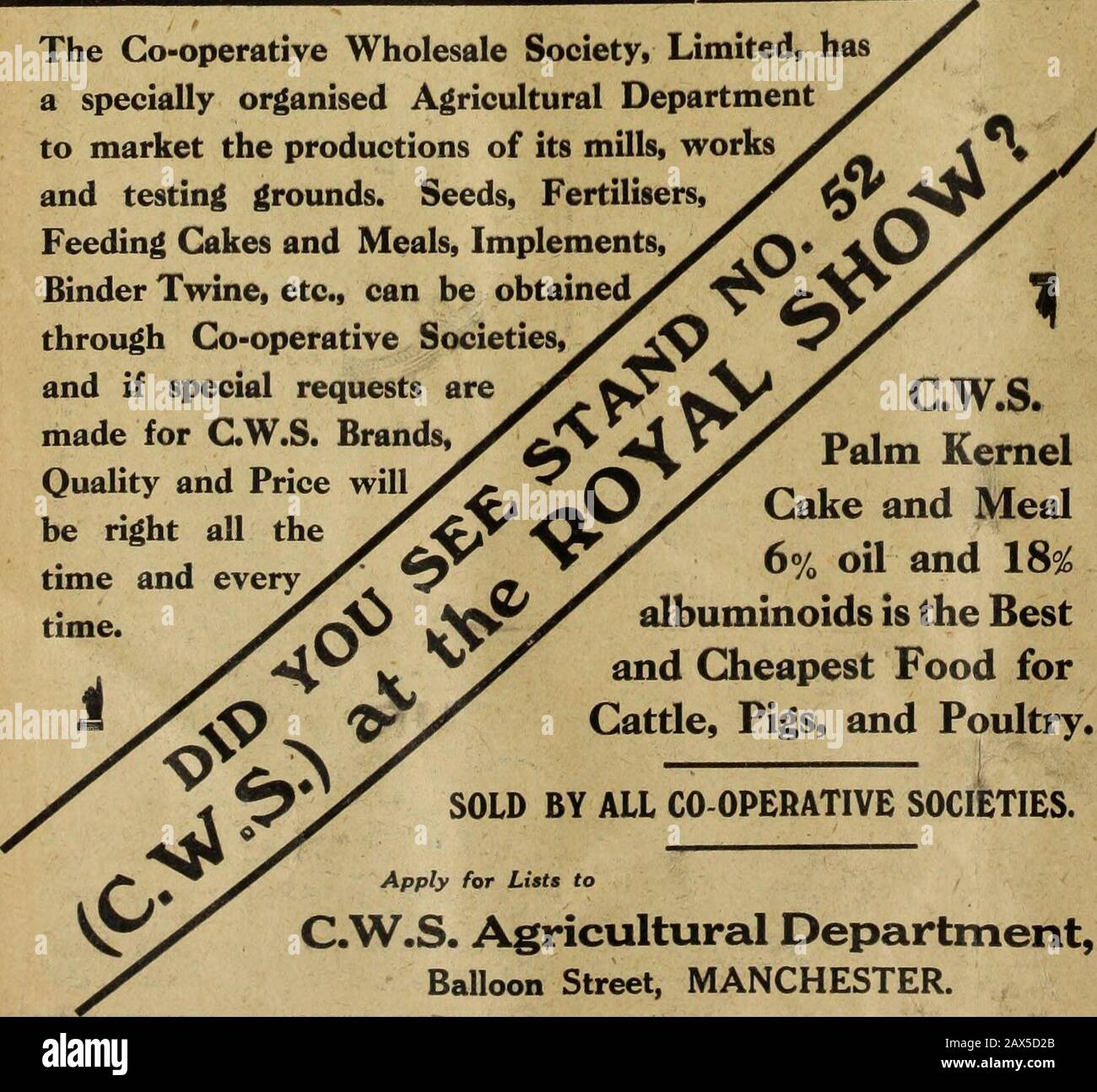

Abraham Greenwood and a handful of others realized that if the individual co-op societies banded together, they could become their own wholesaler. This led to the formation of the North of England Co-operative Wholesale Industrial and Provident Society Ltd, which eventually became the Co operative Wholesale Society. They started in a tiny warehouse in Manchester with a handful of staff. It was risky. If the individual shops didn't buy from the central warehouse, the whole thing would collapse. But they did buy. They bought because they knew that every penny of profit made by the CWS would eventually trickle back down to them, the members.

The Era of "Production for Use"

By the 1870s, the CWS wasn't content just buying and reselling. They wanted to manufacture. This is where the story gets really interesting. They opened a biscuit factory in Crumpsall and a boot factory in Leicester. Why? Because they believed in "production for use, not for profit."

🔗 Read more: Where Did Dow Close Today: Why the Market is Stalling Near 50,000

Think about that for a second.

In a world of Victorian capitalism where child labor and adulterated food were common, the CWS was trying to create a closed loop. They wanted to control the quality of everything their members touched. By the early 20th century, the CWS was arguably the biggest business in the UK. They weren't just a shop; they were a bank, an insurance company, and a global logistics giant.

They bought land in Canada to grow wheat. They bought ships to bring that wheat to their own mills in the UK. They were vertically integrated before that was even a corporate buzzword. If you were a member of a local co-op in 1910, your tea came from CWS plantations, your clothes were made in CWS factories, and your savings were kept in the CWS Bank. It was a literal "Co-operative Commonwealth."

The Great Decline and the Rescue Mission

Nothing stays on top forever. By the 1960s and 70s, the Co operative Wholesale Society was looking... well, a bit dusty. While they were busy managing their massive internal bureaucracy, "private" supermarkets like Tesco and Sainsbury’s were innovating. They were faster, leaner, and better at marketing.

The CWS had become a victim of its own success. It was a giant, slow-moving beast with hundreds of different committees. By the time the 1990s rolled around, the whole movement was in crisis. There were too many small, failing local societies, and the CWS itself was struggling to stay relevant.

💡 You might also like: Reading a Crude Oil Barrel Price Chart Without Losing Your Mind

Then came the turning point in 2000.

The CWS merged with Co-operative Retail Services to form The Co-operative Group. This wasn't just a name change; it was a desperate attempt to consolidate power and save the movement from total irrelevance. A few years later, they almost lost it all again during the Co-op Bank crisis of 2013. That was a dark time. A £1.5 billion "black hole" in the bank's finances, combined with some high-profile leadership scandals, nearly killed the brand.

But here’s the thing: they survived. They sold off the farms and the pharmacies, focused back on convenience food and funerals, and somehow found their footing again. Today, when you see "The Co-op," you're looking at the descendant of that massive wholesale engine.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Model

A lot of people think the Co-op is a charity or a government body. It’s neither. It’s a business owned by its members. When the Co operative Wholesale Society was at its peak, it proved that you could run a multinational corporation without a single traditional shareholder.

The "Divi" (dividend) is the most famous part of this. Instead of profits going to some guy in a suit on Wall Street or in the City of London, the "surplus" was returned to the people who actually spent money in the shops. In many working-class communities, "Divi day" was the only time families could afford new shoes or a piece of furniture. It was a form of forced savings that actually worked.

📖 Related: Is US Stock Market Open Tomorrow? What to Know for the MLK Holiday Weekend

Realities of the Modern Co-operative Group

Today, the spirit of the CWS lives on in Federalism. The Co-operative Group still acts as the primary wholesaler for independent co-op societies across the UK. If you go to a "Midcounties Co-op" or a "Southern Co-op," they are often buying their goods through the central buying power of the Group.

It's a delicate balance.

- Member Voice: Every member has a vote, but in a multi-billion dollar business, how much does one vote really count?

- Competitive Pressure: They have to compete with Aldi and Lidl on price while trying to maintain ethical standards like Fairtrade.

- Sustainability: The CWS was a pioneer in ethical sourcing way before it was cool. They were the first major retailer to switch all their own-brand chocolate to Fairtrade.

The challenge now is keeping that radical 1863 energy alive in 2026. It’s hard to feel like a "member-owner" when you’re just tapping a plastic card for a sandwich.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Consumer

Understanding the history of the Co operative Wholesale Society isn't just a history lesson; it's a way to rethink how you spend your money. If you're tired of "platform capitalism" where a few tech giants own everything, the co-op model offers a legitimate alternative.

- Check the label: When you buy Co-op brand products, look at the sourcing. A huge chunk of their ethical "clout" comes from the fact that they still prioritize direct relationships with producers—a legacy of the old CWS plantations.

- Use your vote: If you have a Co-op membership card, actually vote in the annual general meetings. It sounds boring, but that’s how the leadership is held accountable for things like executive pay and environmental targets.

- Support the independents: Many local societies (like Scotmid or Heart of England) still exist because the CWS provided the wholesale backbone to keep them alive. Shopping there keeps money in your specific region.

- Think beyond retail: The co-operative model works for energy, housing, and even tech. The CWS proved that "wholesale" cooperation is the key to scaling these ideas so they can actually compete with the big guys.

The Co operative Wholesale Society was never perfect. It was often inefficient, prone to infighting, and slow to change. But it remains the most successful experiment in democratic business history. It proved that "the little guy" could build a global empire without selling his soul—or his ownership—to the highest bidder. Whether the modern version can stay true to those roots in an increasingly digital world is the big question, but for now, that 160-year-old foundation is still holding strong.

To really engage with the movement today, download the Co-op app and look at where your "reward" money actually goes. You can choose to funnel your share of the profits into local community projects. It’s a direct digital link back to that Victorian warehouse in Manchester, proving that collective buying power still has some teeth.