Think of Georgia today. You’re likely imagining a humid July afternoon in Savannah where the air feels like a warm, wet blanket and the gnats are relentless. Now, rewind to 1733. When James Oglethorpe and the first group of settlers stepped off the Anne and onto Yamacraw Bluff, they weren't just stepping into a new political experiment. They were walking into a biological and atmospheric buzzsaw. The climate of colonial Georgia was the single greatest factor in whether a family thrived or ended up in a shallow grave within six months. It wasn't just "hot." It was a complete shock to the European system that forced a total rewrite of how people lived, ate, and built their homes.

Honestly, the British had no clue what they were getting into. They expected something akin to the Mediterranean—maybe a bit like southern France or Italy. They envisioned vast vineyards and mulberry trees for a booming silk industry. What they got instead was a subtropical reality that swung wildly between oppressive, mosquito-ridden summers and surprisingly sharp, biting winters. It was brutal.

The Silk Dream vs. The Swamp Reality

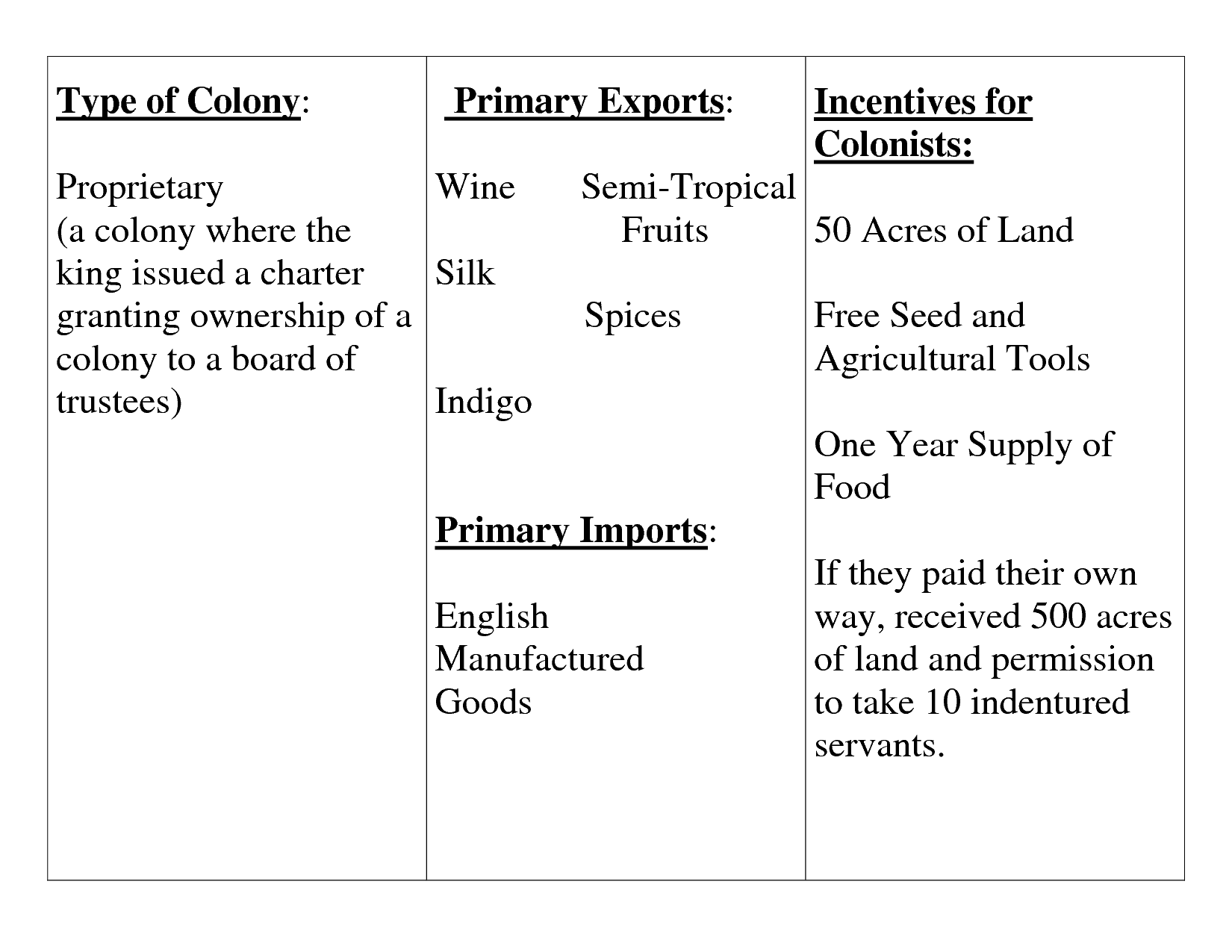

The initial vision for the Georgia colony was almost entirely based on a misunderstanding of latitude. Because Georgia sat at the same latitude as parts of North Africa and Southern Europe, the Trustees in London assumed the climate of colonial Georgia would be perfect for "luxury" crops. They wanted silk. They wanted wine. They wanted olives. They figured the sun would do the heavy lifting.

They were wrong.

The humidity in the Lowcountry is a different beast entirely. In the 1730s, the thick pine barrens and massive river swamps trapped moisture in a way that Londoners couldn't comprehend. While they planted mulberry trees to feed silkworms, the worms often died because the sudden shifts in temperature and the sheer dampness of the coastal air weren't conducive to delicate sericulture. By the time the settlers realized that the "golden" climate was actually a "fever" climate, the silk industry was already stumbling. It basically fell apart because you can't force an ecosystem to be something it’s not.

Surviving the Season of Sickness

If you lived in colonial Savannah or Frederica, your calendar wasn't just marked by months; it was marked by "The Sickly Season." This was usually July through October. The climate of colonial Georgia during these months was a breeding ground for disaster.

✨ Don't miss: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

- Malaria and "Ague": They didn't know about mosquitoes then. They blamed "miasma" or bad air rising from the swamps. But the heat and standing water meant that malaria was an absolute constant.

- Yellow Fever: This came later with the shipping trade, but the climate made it possible for the Aedes aegypti mosquito to flourish.

- Dysentery: Heat meant food spoiled in hours. Water sources often became stagnant and toxic in the August sun.

Historians like Peter Wood have pointed out how the mortality rates in the early years were staggering. You’ve got to realize that in those first few decades, more people were dying than being born. It was "seasoning." If you survived your first two years in the Georgia humidity, you were considered "seasoned." It’s a grim way to describe building an immunity, but that was the reality of the Southern frontier.

The Architecture of Air

People had to adapt or die. You can see the climate of colonial Georgia reflected in the way they eventually learned to build. Look at the "raised cottage" style or the inclusion of deep covered porches (later known as piazzas). They started building houses with high ceilings and large windows aligned to catch the "prevailing breezes" off the river. They weren't just being fancy; they were trying to create a rudimentary form of air conditioning. Without a cross-breeze, a wooden house in a Georgia July becomes an oven.

The "Little Ice Age" and the Winter Surprise

Here’s something most people miss: the 18th century was part of what climatologists call the "Little Ice Age." This means that while the summers were sweltering, the winters were often much harsher than what we see in Georgia today.

Imagine being a settler in a drafty wooden hut. You’ve spent all summer fighting off heat exhaustion and malaria. Then, January hits.

There are colonial records of the Savannah River actually crusting over with ice. In the winter of 1740, temperatures dropped so low that crops froze in the ground. The climate of colonial Georgia was a pendulum. It swung from one extreme to the other, leaving the settlers with very little "mild" weather to actually get work done. They were either too hot to move or too cold to stay dry.

🔗 Read more: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

This volatility made agriculture a nightmare. You couldn't just plant and forget. A late frost in April could—and often did—wipe out the entire food supply for a small settlement like Ebenezer or Darien. The Salzburgers (German religious exiles who settled at Ebenezer) wrote extensively about the difficulty of timing their crops. They were used to the predictable seasons of the Alps; the Georgia coast was a chaotic mess of thunderstorms, droughts, and sudden freezes.

How the Weather Shaped the Economy

Because the silk and wine dreams failed, the settlers had to look at what actually grew in that muck. The answer was rice.

But rice requires a very specific type of environment. It needs the heat, yes, but it also needs massive amounts of water and, crucially, a specific type of labor. This is the dark side of the climate of colonial Georgia. The Trustees originally banned slavery in Georgia, partly because they wanted a "white man's colony" of yeoman farmers. But as the settlers saw the success of South Carolina’s rice plantations, they began to argue that white Europeans simply couldn't work in the "putrid air" of the rice swamps.

They used the climate as a primary justification to overturn the ban on slavery in 1751.

They argued that people of African descent were "better suited" to the heat and the diseases of the Lowcountry. While it's true that some West Africans had a genetic resistance to certain strains of malaria (the Duffy null phenotype), the argument was largely a convenient excuse to build a plantation economy. The climate became a tool for political and social change. It shifted Georgia from a struggling experiment of "the worthy poor" into a wealthy, slave-holding plantation society focused on rice and indigo.

💡 You might also like: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

The Hurricane Factor

Let’s talk about the wind. We think of hurricanes as a modern insurance nightmare, but in the 1700s, they were literal acts of God that could erase a town.

The climate of colonial Georgia included a cycle of tropical storms that the settlers weren't prepared for. In September 1752, a massive hurricane decimated the coast. It pushed a storm surge so high that it reportedly covered parts of the barrier islands and destroyed crops and shipping. There was no Doppler radar. No hurricane hunters. You just saw the barometer drop, the sky turn a weird shade of orange, and then you prayed your roof stayed on.

These storms reinforced the idea that nature in the South was powerful, unpredictable, and slightly hostile. It bred a certain type of resilience—or perhaps a certain type of fatalism—in the people who stayed.

Why This History Matters Today

Understanding the climate of colonial Georgia isn't just a trip down memory lane. It explains why Savannah looks the way it does. It explains why the early economy struggled and then exploded. It even explains the food. Why do we eat highly seasoned, preserved, or fried foods? Much of it comes from the necessity of dealing with heat and spoilage in a world without refrigeration.

If you’re researching this for a project or just because you’re a history nerd, here are some actionable ways to dive deeper into the actual records:

- Read the Colonial Records of Georgia: Look for the letters of Henry Ellis, the second royal governor. He was a scientist of sorts and actually performed experiments on the heat. He famously wrote about how the sun in Savannah could melt the wax on his desk.

- Visit the Wormsloe State Historic Site: Don't just look at the trees. Pay attention to the ruins of the "tabby" structures. Tabby (a mix of lime, sand, and oyster shells) was a direct response to the climate. It was a building material that could breathe and withstand the humidity better than imported brick or rotting timber.

- Study the "Miasma Theory" maps: Look at where the early settlers placed their "pesthouses" (quarantine stations). You'll see they were always downwind or on isolated islands, showing how they tried to use the climate and geography to manage disease before they understood germ theory.

The climate of colonial Georgia was the ultimate filter. It weeded out the unprepared and forced the survivors to adapt in ways that still define the American South today. It wasn't just a backdrop; it was the lead character in the story of the 13th colony.

To truly grasp the impact of the environment on early American life, your next steps should involve looking at primary source weather journals. The most famous "weather diary" from the era comes from Thomas Jefferson, but for Georgia specifically, look into the journals of the Moravians and Salzburgers. Their meticulous notes on rainfall, crop failure, and daily temperatures provide a raw, unvarnished look at what it was like to sweat through a summer in 1740. You can often find these digitized through the Georgia Historical Society or the Digital Library of Georgia. Focusing on these firsthand accounts will give you a sense of the "lived" climate that standard history books often gloss over.