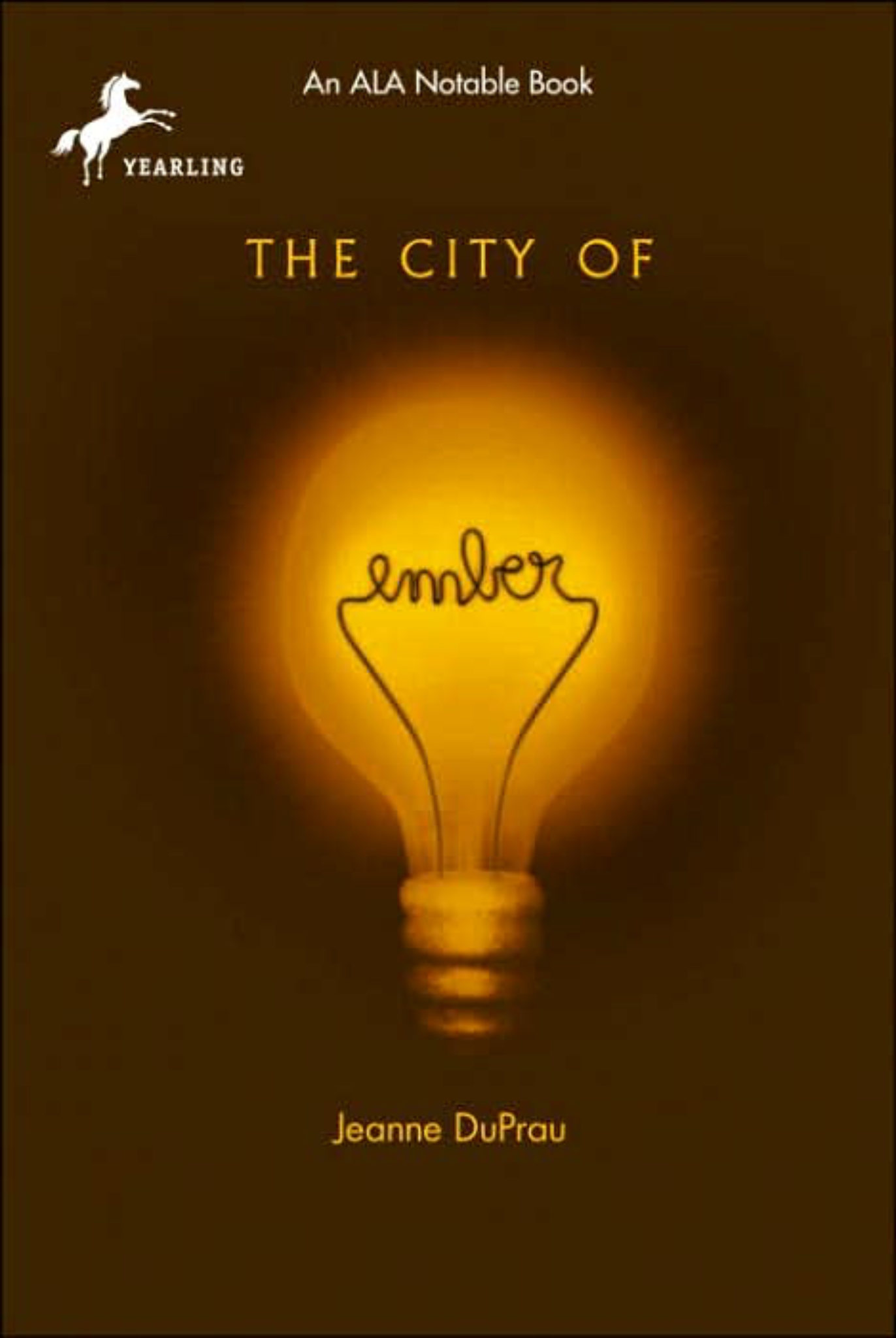

The lights are flickering. For the people living in the last refuge of humanity, that isn't just a minor annoyance—it’s a death sentence. When Jeanne DuPrau published The City of Ember book in 2003, she wasn't just writing another middle-grade adventure. She was tapping into a very specific, very primal fear of the dark.

It’s been over twenty years. Yet, we’re still talking about Lina Mayfleet and Doon Harrow. Why?

Maybe it’s because the world feels a bit more fragile lately. Or maybe it’s just because the image of a city powered by a massive, failing generator in the middle of an eternal night is honestly terrifying. People usually remember the movie—which was fine, honestly—but the book is where the actual dread lives. It’s a masterclass in world-building that doesn’t rely on magic wands or chosen ones with superpowers. It's just two kids with a box of matches and a very old, very crumpled piece of paper.

What Actually Happens in the City of Ember

The premise is pretty straightforward, but the execution is what makes it stick. The "Builders" designed Ember to last 200 years. They left instructions in a locked box, meant to be passed from mayor to mayor. But humans are, well, human. A corrupt mayor dies, the box gets shoved in a closet, and the countdown keeps ticking.

By the time we meet Lina, the city is 241 years old. Everything is running out. Lightbulbs are precious. Canned peaches are basically gold.

Lina and Doon are twelve. That’s "Assignment Day" age in Ember. Lina wants to be a Messenger, sprinting through the streets to deliver news because there are no phones. Doon wants to be in the Pipeworks. He thinks he can fix the generator. He's wrong, of course. The generator is way past its expiration date.

When Lina’s baby sister, Poppy, finds a weird box and starts chewing on a piece of paper, the story actually kicks off. That paper is the "Instructions for Egression." It’s the map out. But it's in shreds.

The Realism of the Dystopia

What DuPrau gets right—and what most YA authors miss—is the bureaucracy of the apocalypse. Ember isn't ruled by a mustache-twirling villain (though Mayor Cole is a greedy jerk). It’s failing because of entropy.

💡 You might also like: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

The shops are empty. You can't just buy a new coat. You have to find someone who’s willing to trade a used one for some colored pencils. This scarcity feels real. It’s not "theatrical" poverty; it’s the slow, grinding realization that the light is literally going to stay off one day soon.

Why People Still Obsess Over the Ending

The ending of The City of Ember book is one of those literary moments that stays in your brain. For the characters, the "surface" is a myth. They don't even have a word for "sun" or "tree" that carries any real meaning.

When they finally climb out—and the sequence in the cave is genuinely claustrophobic—they experience the sunrise for the first time. DuPrau writes this with such sensory intensity that you almost feel like you're seeing it for the first time too. The colors. The scale. The sheer overwhelming brightness of a world that isn't powered by a vibrating machine underground.

But there’s a catch.

They look down. They see a hole in the ground. They realize their entire world, their entire history, was just a tiny speck in a cave. They throw a rock down with a note attached, hoping someone sees it. It’s a cliffhanger, sure, but it’s also a massive shift in perspective. It reminds you that we often live in "cities" of our own making, unaware of the massive reality just outside the walls.

The Science and Logistics (Sorta)

Okay, let’s get nerdy for a second. Could Ember actually exist?

Technically, keeping a city of thousands alive underground for two centuries is a logistical nightmare. You need oxygen scrubbers. You need a massive amount of hydroponics. You need waste management that doesn't involve just dumping things in a river.

📖 Related: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

DuPrau skips some of the hardcore hard-sci-fi details, but she nails the psychology. People in Ember are terrified of the "Long Darkness." This isn't just a fear of the dark; it's a cultural trauma.

- The Power Source: A hydroelectric generator powered by an underground river. Plausible? Yes. Durable for 240 years without replacement parts? Highly unlikely.

- The Food: Mostly canned goods and greenhouse-grown potatoes. The "Great Vitamin Scare" mentioned in the lore is a nice touch of realism.

- The Genetics: The Builders chose 200 people (100 men, 100 women) to start the colony. They were mostly elderly to ensure they didn't have "memories" of the surface to pass down to the kids. This is dark. It’s essentially state-sponsored amnesia.

Comparing the Book to the 2008 Movie

Honestly, the movie gets a bad rap. Bill Murray as the Mayor was inspired casting. Saoirse Ronan was great as Lina. But the movie added a bunch of "action" stuff that wasn't in the book—like giant mutated moths and a mechanical riding sequence in the Pipeworks.

The book is quieter. It’s more about the mystery.

In the book, the tension comes from the ticking clock and the social decay. In the movie, it's about big set pieces. If you've only seen the film, you're missing the psychological weight of Lina's grandmother losing her mind while searching for "something lost" or the quiet despair of the greenhouse workers. The book is definitely the superior version.

Key Themes for Modern Readers

You might think a book for 10-year-olds wouldn't have much to say to adults, but you'd be wrong.

1. Environmental Stewardship

Ember is a closed system. When they run out of lightbulbs, there aren't any more. Period. It's a perfect metaphor for resource depletion. We live on an island in space, and like the citizens of Ember, we're often too busy with our daily drama to notice the "generator" is sparking.

2. Truth and Corruption

Mayor Cole is hoarding food. He knows the city is dying, but he wants to live well for the few years he has left. It’s a stinging critique of short-term thinking in leadership.

👉 See also: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

3. The Power of Curiosity

Doon is considered a "difficult" kid because he asks too many questions. In Ember, asking questions is dangerous because the answers are terrifying. But without his curiosity, everyone would have died in the dark.

How to Read the Rest of the Series

A lot of people don't realize The City of Ember book is actually the first of four.

If you're going to dive back in, here’s the deal:

- The People of Sparks: This picks up immediately after they reach the surface. It’s basically a western. It deals with the conflict between the Emberites and the people already living on the surface. It’s gritty.

- The Prophet of Yonwood: This is a prequel. Most people skip it. Don't. It explains why the world ended and why Ember was built in the first place. It’s set in a world gripped by war and religious fervor.

- The Diamond of Darkhold: This brings Lina and Doon back to Ember to find a "lost" technology. It’s a solid conclusion to the character arcs.

Actionable Takeaways for Fans and New Readers

If you're revisiting this world or introducing it to someone else, there are a few ways to really "get" the experience.

First, read it with a focus on the sensory details. Notice how often DuPrau mentions the smell of the air or the specific type of darkness. It makes the ending hit much harder.

Second, look into the real-world "Seed Vaults" like the one in Svalbard, Norway. The "Builders" in the book weren't just a plot device; they represent a very real human impulse to preserve our species against catastrophe. Comparing the fictional Ember project to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a fascinating rabbit hole.

Finally, check out the graphic novel adaptation by Niklas Asker. It captures the "industrial-decay" aesthetic of the city perfectly. It’s a great way to visualize the Pipeworks without the over-the-top CGI of the movie.

Ember isn't just a story about a dark city. It's a story about what happens when we stop paying attention to the systems that keep us alive. Whether you're twelve or forty, that's a message that sticks.

To get the most out of the series, start with the original 2003 novel, then move directly into The People of Sparks to see how the social dynamics shift from "survival" to "politics." If you want the full lore, save The Prophet of Yonwood for third, even though it's a prequel—it makes more sense once you've seen the "future" it creates. Don't bother with the movie tie-in editions; find the original hardcover or the 20th-anniversary paperback for the best cover art and map layouts.