You flip a switch. The light comes on. It feels like magic, but it’s just physics doing its job. Most of us think we understand the definition of a circuit, yet when you actually look at the guts of a machine, it gets weirdly complicated.

A circuit isn't just a wire.

Basically, it's a closed loop. If you don't have a loop, you don't have a circuit; you just have a bunch of metal sitting there doing nothing. Electricity is picky. It wants to go home. It leaves a power source, travels through some stuff, and has to get back to the other side of that source. If there is a gap—even a microscopic one—the whole party stops. That’s why your broken charging cable won't work even if "most" of the wires are still touching. Electrons are all-or-nothing kind of travelers.

The Bare Bones of a Real Circuit

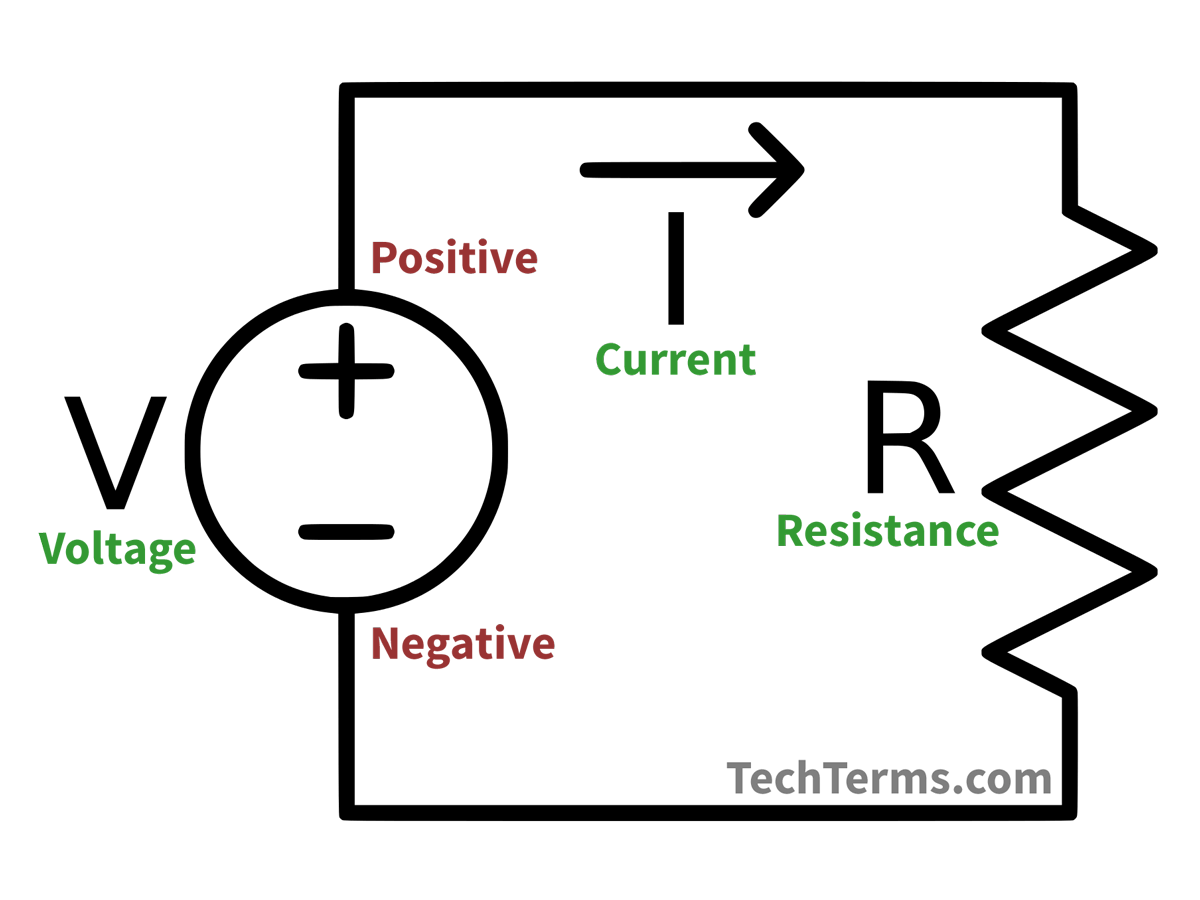

To really nail down the definition of a circuit, you need to look at the three (sometimes four) musketeers of the electronics world.

First, the source. Think of a battery or a wall outlet. This is the "push." In technical terms, we call this voltage. Without voltage, electrons are just idling. They need a reason to move.

Second, the conductor. Usually, this is copper. Why copper? Because it’s cheap and its atoms are "loose" with their electrons. They don't mind passing them along like a bucket brigade.

💡 You might also like: Getting Porn Channels on Roku Without Getting Scammed or Banned

Third, the load. This is the point of the whole exercise. It’s your lightbulb, your toaster, or your smartphone's processor. The load resists the flow of electricity and turns that energy into something useful—like heat, light, or a TikTok video.

Lastly, there’s often a switch. It’s the gatekeeper. When the switch is "off," the circuit is "open." That sounds backwards, right? Open sounds like it should be flowing. But in electronics, an open circuit means there’s a hole in the bridge. No one is crossing.

The Drift Velocity Myth

Here’s a fun fact that usually blows people's minds: individual electrons move incredibly slowly. Honestly, they crawl. We’re talking about a few millimeters per second. If you were waiting for a specific electron to travel from your wall outlet to your lamp, you’d be waiting all night.

So why does the light turn on instantly?

It’s the field. Think of a garden hose already full of water. The moment you turn the tap on at one end, water pops out the other. You didn't wait for the new water to arrive; you just pushed the water that was already in the pipe. In a circuit, the electromagnetic wave travels at nearly the speed of light. That’s what actually carries the energy. The electrons are just the medium.

Different Flavors of Loops

Not all circuits are built the same way. If you’ve ever dealt with old-school Christmas lights, you know the pain of a "series" circuit. One bulb dies, the whole strand goes dark. It’s a single-track mind. The electricity has one path, and if any part of that path breaks, the game is over.

Most of your house is wired in "parallel."

This is way smarter. In a parallel circuit, the electricity has options. It’s like a highway with multiple lanes. If there’s an accident in the right lane (your microwave blows a fuse), the traffic (electricity) can still flow through the left lane to keep your fridge running. This is why you can turn off the bathroom light without the TV in the living room dying.

Short Circuits and Why They Smell Like Burning

We’ve all heard the term "short circuit." People use it to mean "it’s broken," but the technical definition of a circuit that is "shorted" is actually quite specific.

It’s a shortcut.

🔗 Read more: Finding RC Cars Under $70 That Don’t Break on Day One

Electricity is lazy. It takes the path of least resistance. If a stray wire touches the "hot" side and the "neutral" side before hitting the load (like a lightbulb), the electricity skips the bulb and rushes through that shortcut. Because there’s no "load" to slow it down, the current spikes to insane levels. Things get hot. Things melt. Things catch fire. This is why we have fuses and circuit breakers—they’re basically the "emergency brakes" of your home.

The Nuance of AC vs. DC

The definition of a circuit changes slightly depending on which way the wind is blowing—or rather, which way the electrons are flowing.

- Direct Current (DC): This is the battery life. Electrons flow in one direction, like a one-way street. Your phone, your laptop, and your car all live in a DC world.

- Alternating Current (AC): This is what comes out of your wall. The electrons don't actually "travel" anywhere. They vibrate back and forth 60 times a second (in the US). It’s like a saw moving back and forth. It still does work, but it never leaves the neighborhood.

Tesla and Edison literally fought a "war" over this. Edison wanted DC everywhere, but it couldn't travel long distances without losing power. Tesla (and Westinghouse) pushed AC because you can use transformers to boost the voltage, send it hundreds of miles, and then drop it back down for the toaster. Tesla won, which is why your neighborhood has those big gray cans on the power poles.

What Most People Miss: The Return Path

Grounding is the part that confuses everyone. You see that third prong on a plug? That’s the "get out of jail free" card for electricity.

If a wire inside your toaster comes loose and touches the metal casing, the whole toaster becomes "live." If you touch it, you become the circuit. You are the path to the ground. That’s bad. The ground wire provides a safer, easier path for that stray electricity to go straight into the dirt instead of through your heart. It’s a safety loop that stays empty 99% of the time.

Integrated Circuits: The Modern Marvel

We’ve moved far beyond wires and lightbulbs. Nowadays, we have integrated circuits (ICs). These are the "chips" in your brain—I mean, your phone.

Instead of copper wires, they use microscopic traces of silicon. They pack billions of "switches" (transistors) into a space smaller than your fingernail. But here’s the kicker: the fundamental definition of a circuit hasn't changed. Even in a 5-nanometer chip, you still need a source, a path, and a return. It’s just miniaturized to a level that feels like sci-fi.

Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel, famously predicted that the number of transistors on these circuits would double every couple of years. We call it Moore’s Law. We’re reaching the physical limits of that now because atoms are only so small, but the logic remains the same.

📖 Related: Buying a cover computer macbook air: What Most People Get Wrong About Protection

Actionable Next Steps for the Curious

If you’re looking to move from theory to practice, here is how you can actually use this knowledge:

- Audit Your Surge Protectors: Look for the "Joules" rating. If it’s under 1000, it’s basically a glorified extension cord. Get a real one to protect your expensive "integrated circuits."

- Identify Your Breaker Box: Go to your electrical panel. Figure out which switch controls which room. Label them. It’s a boring Saturday task that saves your life during a leak or a fire.

- Learn to Solder: If you want to understand circuits, build one. Buy a $20 soldering kit and a "blink-an-LED" project. Seeing the physical path makes the abstract concept click.

- Check for "Vampire Loads": Many circuits stay "closed" even when the device is off. Anything with a standby light or a clock is drawing power. Unplugging them actually breaks the circuit and saves money.

Understanding a circuit is really about understanding how energy moves through our world. It's the difference between being a passive user of technology and someone who actually gets how the gears turn. Next time you flip that switch, remember: you’re completing a loop that might stretch all the way back to a power plant hundreds of miles away. It’s a big loop. Make sure it stays closed.