It’s a story we think we know by heart. The flickering candles on tiny fir trees. The haunting melody of "Stille Nacht" drifting across No Man's Land. Enemies dropping their rifles to kick a tattered soccer ball around the frozen mud of Flanders. It sounds like a Hollywood script, honestly. But the Christmas armistice World War 1 was far messier, more localized, and significantly more subversive than the greeting card version suggests.

The war was supposed to be over by then. "Home by Christmas" was the lie every soldier had been fed in August 1914. Instead, by late December, hundreds of thousands of men were shivering in waterlogged ditches stretching from the Swiss border to the North Sea. They were exhausted. They were mourning. And, perhaps most importantly, they were close enough to the "enemy" to hear them cough, smell their tobacco, and realize they were just as miserable.

Why the truce wasn't a single event

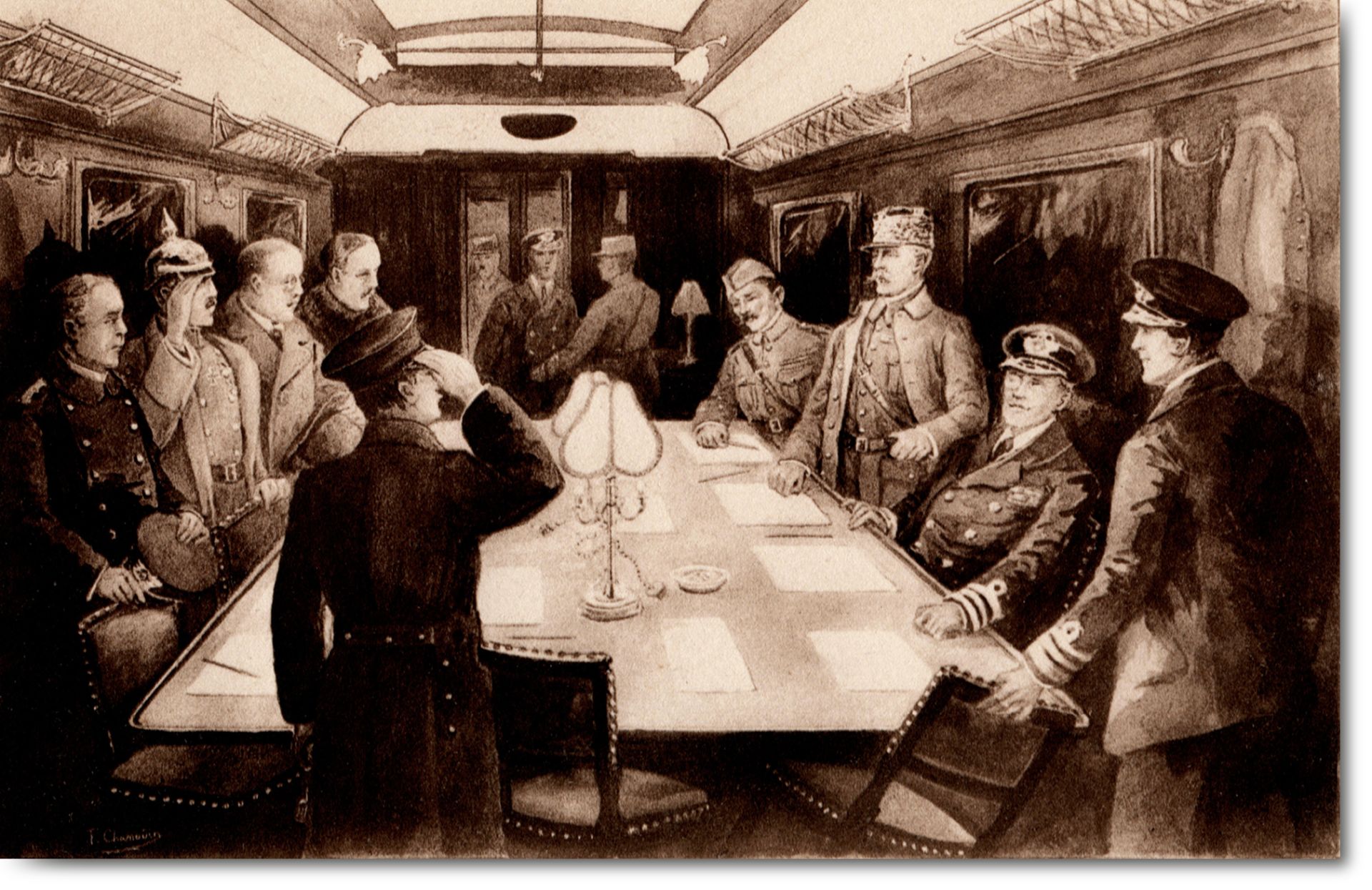

When people talk about the Christmas armistice World War 1, they often treat it like a top-down order. It wasn't. In fact, the high commands on both sides—General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien for the British and the German Oberste Heeresleitung—were absolutely terrified of it. Smith-Dorrien actually issued a warning in early December against "fraternization," fearing it would "destroy the offensive spirit."

He was right to be worried.

The truce was a series of small, spontaneous outbreaks of humanity. In some sectors, like near the Belgian village of Ploegsteert (the "Plugstreet" of British slang), the truce was extensive and lasted for days. In others? The war just kept grinding on. Men were shot while trying to initiate peace. There was no universal whistle that blew to stop the killing. It was a patchwork of peace.

The first sparks of the "Live and Let Live" system

Historian Tony Ashworth wrote extensively about the "Live and Let Live" system that developed in the trenches. It’s basically the idea that if you don't shell my breakfast, I won't shell yours. This wasn't about being buddies; it was about survival. By the time Christmas Eve arrived, this unspoken understanding had already primed the pump.

On December 24, 1914, the weather turned. The relentless rain stopped, and a hard frost set in, turning the mud into something solid. This change in atmosphere seemed to shift the mood. German soldiers began placing Tannenbäume (Christmas trees) on their parapets.

✨ Don't miss: Ohio Polls Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About Voting Times

Captain Bruce Bairnsfather, a famous cartoonist and soldier, described the scene vividly. He recalled seeing a German soldier waving his arms and then, slowly, figures began emerging from the gloom. Imagine the tension. You’ve spent months trying to kill these people, and suddenly they’re walking toward you without a gun. It’s terrifying. It’s also incredibly brave.

The soccer match myth vs. reality

Everyone wants to talk about the soccer match. Did it happen?

Yes, but probably not the way you’re imagining it. There wasn't a 90-minute FIFA-regulated game with jerseys and a referee. It was mostly "kick-abouts." Private Ernie Williams of the 6th Cheshire Regiment recalled a game in a 1983 interview, noting that about a couple hundred people were involved. They used a leather ball, but in other sectors, they used tin cans or sandbags stuffed with straw.

Records from the 133rd Saxon Regiment and the Scottish Seaforth Highlanders suggest a game occurred near Frelinghien. The Germans allegedly won 3-2. Honestly, the score doesn't matter. What matters is that for a few hours, the "Huns" and the "Tommies" weren't targets. They were just guys playing a game.

What they actually talked about

The conversations weren't about grand politics or the causes of the war. They were mundane. Soldiers swapped buttons. They traded British "Bully Beef" for German sausages. They shared photos of their wives.

One of the most poignant aspects of the Christmas armistice World War 1 was the joint burial services. In the "No Man's Land" between the trenches, bodies had been rotting for weeks because it was too dangerous to retrieve them. During the truce, soldiers from both sides worked together to dig mass graves. They stood side-by-side as a chaplain or an officer read the 23rd Psalm. It’s hard to go back to shooting someone after you’ve helped them bury their dead.

🔗 Read more: Obituaries Binghamton New York: Why Finding Local History is Getting Harder

Why it never happened again

The 1914 truce was a unique fluke of history. By 1915, the war had turned much darker. The use of poison gas at Ypres and the sinking of the Lusitania had hardened hearts. Plus, the generals made sure it couldn't happen again.

Artillery barrages were ordered specifically for Christmas Day in subsequent years to prevent any "quiet" moments. Orders were clear: fraternization was high treason, punishable by death. The "innocence" of 1914 had been replaced by the industrial-scale slaughter of Verdun and the Somme.

The role of the "Postal Service" peace

An overlooked detail of the truce is how much it relied on the mail. Both sides were receiving huge amounts of "Princess Mary" tins (for the British) and gift boxes from the Kaiser. These boxes contained tobacco, chocolate, and even pipes. Having a surplus of "luxuries" gave the men something to trade, which acted as a catalyst for the initial meetings.

Modern misconceptions and the "German side"

We often hear the British perspective because of the wealth of diaries left behind, but German accounts are just as moving. Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch of the 134th Saxon Infantry Regiment wrote in his diary about how "marvelously wonderful and yet how strange" it was to see the English and Germans standing together.

It’s worth noting that the truce was most common in sectors held by Saxon or Bavarian troops. The Prussians, who were seen as more professional and rigid, were much less likely to participate. In fact, a young corporal named Adolf Hitler, who was serving with the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry, reportedly hated the idea of the truce, grumbling that such things "should not happen in wartime."

The breakdown of the peace

The end of the truce was as strange as the beginning. In some places, it ended at midnight on Christmas. In others, it lasted until New Year’s Day. There are reports of soldiers firing shots into the air to signal that the "war was back on," a way of saying "get your heads down, we have to start shooting now."

💡 You might also like: NYC Subway 6 Train Delay: What Actually Happens Under Lexington Avenue

One British soldier recalled a German officer visiting their trench to apologize that his Colonel had ordered them to start firing again. They had built a weird, temporary bond that the machine of war had to work hard to break.

Lessons from the mud

The Christmas armistice World War 1 wasn't a peace movement. It didn't end the war. It didn't even slow it down much in the long run. But it proved that the "enemy" is a construct created by people in offices miles away from the front lines.

When you look at the primary sources—the letters from men like Private Henry Williamson or the sketches by Bruce Bairnsfather—you see a rejection of propaganda. The soldiers realized that the guy in the opposite trench was also cold, also missed his mom, and also didn't really want to be there.

How to research this yourself

If you want to go deeper than the myths, you need to look at specific unit war diaries. The National Archives in the UK has digitized many of these. Look for the December 1914 entries for the North Staffordshire Regiment or the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

You can also visit the Christmas Truce Memorial in Mesen, Belgium. It’s a quiet spot, often overlooked by the big bus tours, but it sits right where some of the most intense fraternization happened.

Actionable steps for history buffs

- Read the original letters: Check out the Imperial War Museum’s online archives. Search for "1914 Christmas" to see the actual handwriting of the men who were there.

- Differentiate the sectors: When reading accounts, identify the regiment. You’ll find that the truce was almost non-existent in areas held by the French or Belgians, whose land was being occupied and who (rightfully) felt much more animosity toward the Germans.

- Look at the 1915 "Silent Night" attempts: Research why the attempts to repeat the truce in 1915 failed. It highlights the shift from a "gentleman’s war" to total war.

- Verify the soccer locations: Use trench maps (available on sites like the National Library of Scotland) to overlay 1914 positions with modern Belgian fields. This lets you see exactly where those "kick-abouts" likely occurred.

- Check out the "Christmas Truce" song by Sabaton or the film "Joyeux Noël": While these are dramatizations, they use real historical anecdotes as their foundation. Compare the film scenes to the actual diary entries of Lieutenant Sir Edward Hulse to see what was "Hollywood-ized."