When you think about the most deadly natural disaster in history, your mind probably jumps to the big ones everyone talks about. Maybe the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami or that massive earthquake in Haiti. You might even think of the Black Death, though that’s technically a pandemic. But if we’re talking about a single environmental event that absolutely devastated a population, the 1931 Central China Floods sit in a category of their own. It’s a story of water, hunger, and a complete breakdown of human systems that most people outside of academia basically ignore.

Honestly, the numbers are hard to wrap your head around. We aren't just talking about a few thousand people. Estimates from sources like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and historians like Chris Courtney suggest the death toll ranged from 1.4 million to as high as 4 million people. To put that in perspective, that's like the entire population of Los Angeles just vanishing over the course of a few months.

It wasn't just a "bad storm." It was a perfect storm of climate, politics, and bad luck.

Why the 1931 Central China Floods are still the benchmark for catastrophe

So, what actually happened? Well, the setup started long before the water hit. China had been through a brutal drought from 1928 to 1930. The ground was baked hard, like concrete. Then, the winter of 1930 brought heavy snows, followed by a massive spring thaw and some of the most intense rain the region had ever seen. Usually, the Yangtze River area gets maybe two or three cyclonic storms a year. In July 1931 alone, there were nine.

Nine.

The water didn't just rise; it exploded across the landscape. The Yangtze, the Huai, and the Yellow Rivers all breached their banks. Imagine a wall of water hitting a population that was already struggling with civil war and poverty. The Republic of China was basically in chaos at the time, fighting internal battles, which meant the dikes and dams hadn't been maintained. When the water came, there was nothing to stop it.

Most people assume everyone drowned. They didn't. In fact, a huge chunk of those millions of deaths didn't happen in the water. They happened in the aftermath. If you survived the initial surge, you were suddenly living in a world where the sewage system (what little there was) had mixed with your drinking water. Cholera and typhus tore through refugee camps. People were eating bark and weeds because the rice crops—the literal lifeblood of the region—were rotting under eight feet of murky water.

👉 See also: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

The ripple effect of a broken environment

It’s kinda wild to think about how much the environment dictates our survival. In 1931, the flooding covered an area about the size of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut combined. This wasn't a localized flash flood. This was a total regional collapse.

John Lossing Buck, an American agricultural economist who was on the ground back then, surveyed the damage and realized that the economic impact was just as lethal as the water. Millions of cattle drowned. Think about that. No cattle meant no way to plow for the next season. No seeds meant no future. It was a compounding interest of misery.

Historically, this event gets overshadowed because 1931 was also the year Japan invaded Manchuria. The world’s eyes were on the looming threat of World War II, so the fact that millions were starving in the Yangtze basin became a footnote in many Western history books. But for the people living through it, it was the end of the world.

A breakdown of the lethal mechanics

To understand how this became the most deadly natural disaster, you have to look at the three distinct waves of death.

- The Initial Inundation: This is the cinematic part. Dikes failing at night. Entire villages swept away in seconds. If you lived in a low-lying area near the Gaoyou Lake, you essentially had no chance once the levees gave way on August 26th.

- The Disease Phase: This is what experts like Mary C. Wright have pointed out in historical analyses of the era. Once the water sits, it becomes a petri dish. When you have millions of displaced people huddled on narrow strips of dry land, social distancing isn't a thing. Measles, malaria, and dysentery became the primary killers.

- The Famine: This lasted well into 1932. The floods destroyed the "Rice Bowl" of China. Without the ability to replant, the survivors simply ran out of fuel. There are haunting accounts from the time of parents selling their children just so they would have a chance to be fed by someone else. It's grim, but it's the reality of a total systemic failure.

What we get wrong about modern risk

You might think, "Well, that was 1931. We have satellites and concrete dams now."

True. We do. But the 1931 floods teach us that the "most deadly" tag isn't just about the weather; it's about vulnerability. Today, the Yangtze basin is more crowded than ever. While the Three Gorges Dam is a marvel of engineering designed to prevent exactly this kind of thing, the stakes are also much higher.

✨ Don't miss: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

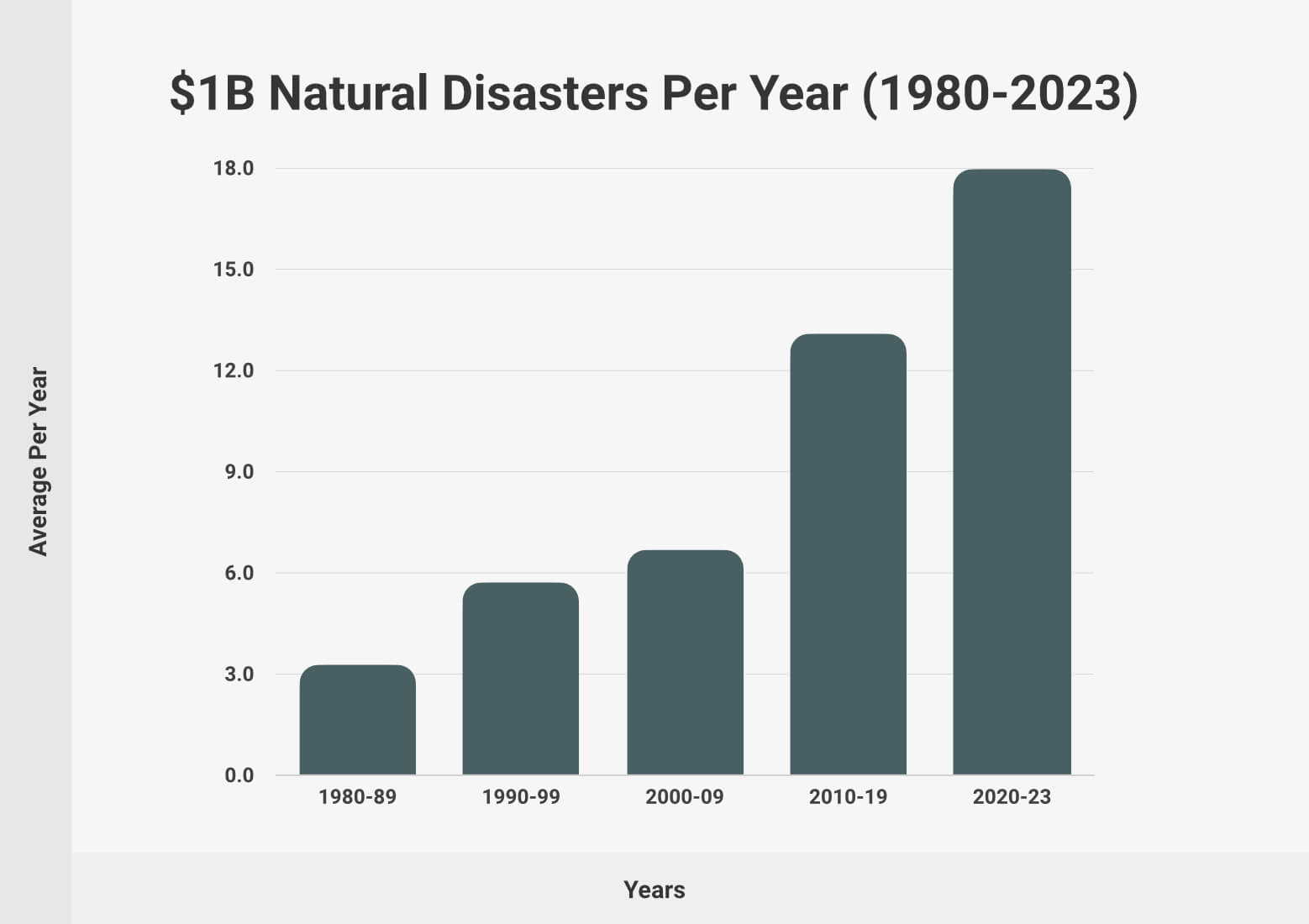

If a 1-in-500-year rain event happens again—and with climate shifts, those "1-in-500" numbers are looking more like "1-in-50"—the infrastructure has to be perfect. In 1931, the failure was human. The dikes were poorly made. The government was distracted. The relief effort was underfunded.

Technology is great, but it doesn't solve the problem of human density. We still build in floodplains. We still rely on single-source food chains. The 1931 disaster wasn't a freak accident; it was a demonstration of what happens when a natural cycle hits a fragile society.

Why this history matters right now

When we talk about the most deadly natural disaster, we usually treat it like a trivia point. A "did you know?" for a dinner party. But looking at the 1931 records—like the reports from the National Flood Relief Commission—shows us a blueprint of how things fall apart.

It also shows us how things can be fixed. After the 1931 event, China's approach to water management changed forever. They realized you can't just build a wall and hope for the best. You need integrated systems. You need international cooperation. Even back then, organizations like the League of Nations were trying to send help, though it was often too little, too late.

Actionable insights for a changing world

Knowing about the 1931 floods isn't just a history lesson. It’s a framework for understanding modern risk management. If you want to take this knowledge and apply it to how you view the world today, consider these points.

Pay attention to secondary risks. In any disaster, the thing that kills you usually isn't the thing that makes the headlines. It’s the lack of clean water two weeks later. It’s the supply chain collapse three months later. If you're looking at your own local risks, look at the "second-tier" consequences.

🔗 Read more: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

Infrastructure is only as good as its maintenance. The 1931 disaster happened because people forgot to care for the levees during times of peace. Whether it's the power grid or the local dam, the quiet years are when the real work happens. Supporting local infrastructure funding isn't sexy, but it’s literally life-saving.

Understand the "Compounding Effect." A flood is bad. A flood during a civil war is a catastrophe. A flood during a civil war following a drought is a world-ender. When assessing global news, look for where multiple crises intersect. That is where the next "most deadly" events are likely to occur.

Support standardized relief efforts. The 1931 floods proved that fragmented relief doesn't work. Modern organizations like the Red Cross or the World Food Programme rely on established protocols to prevent the kind of disease outbreaks that killed millions in the 1930s.

The 1931 Central China Floods serve as a reminder that nature doesn't need to be malicious to be devastating; it just needs to be persistent. By understanding the sheer scale of what happened along the Yangtze nearly a century ago, we can better appreciate the thin line that separates a modern city from a historical footnote.

History has a funny way of repeating itself, but only if we stop paying attention to the lessons written in the mud of the 1931 riverbanks.