Let’s be honest for a second. When you see the acronym CDC and childhood obesity mentioned in the same headline, your brain probably prepares for a lecture. You expect a dry list of "eat your veggies" and "get outside." But the reality on the ground—the stuff the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is actually tracking—is way more complicated, and honestly, a bit more frustrating than most people realize.

We are looking at a situation where about one in five children in the United States are living with obesity. That’s nearly 15 million kids. It’s not just a "lifestyle choice" or a lack of willpower. It’s a systemic, biological, and environmental tangle that the CDC has been trying to untie for decades.

The CDC and Childhood Obesity: It’s Not Just About the BMI

The BMI is a tool. It's not a perfect diagnostic. The CDC defines childhood obesity as having a Body Mass Index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile for children of the same age and sex.

But here is the thing.

The CDC updated their growth charts recently—specifically the "extended" growth charts—because so many children were flying off the top of the old 2000 versions. When the standard charts can't even track the level of severe obesity we’re seeing, you know the baseline has shifted. This isn't just a trend. It's a fundamental change in how human bodies are developing in a modern environment.

Karen Hacker, MD, MPH, who directs the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, has frequently pointed out that this isn't a problem parents can solve by just hiding the cereal box. We are talking about a "toxic" food environment. We’re talking about "food deserts" where the only accessible meal is at a gas station.

Why the 2026 Perspective Matters

We used to think this was a simple math problem: calories in versus calories out.

Science says no.

💡 You might also like: Can DayQuil Be Taken At Night: What Happens If You Skip NyQuil

The CDC’s current research focuses heavily on Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). This is a fancy way of saying that the zip code a child lives in is a better predictor of their weight than their DNA. If a kid doesn’t have a sidewalk to walk on or a park that’s safe to play in, how are they supposed to meet the physical activity guidelines? They can't.

What the CDC Actually Recommends (Beyond the Basics)

The CDC doesn't just put out posters. They fund the State Physical Activity and Nutrition (SPAN) program. This is where the real work happens. They are trying to bake health into the infrastructure of cities.

- Improving nutrition standards in Early Care and Education (ECE) settings. Think about where toddlers spend 8 to 10 hours a day. If that center serves sugar-sweetened beverages, the kid is starting behind the curve before they even hit kindergarten.

- Voucher programs for farmers' markets. The CDC works with local health departments to make fresh produce cheaper than a bag of chips. It's a slow burn, but it works.

- The "Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child" (WSCC) model. This is a framework that looks at the school as a hub for health, not just a place to learn algebra.

It’s about "stealth health." You don't tell the kid to lose weight; you change the environment so that the healthy choice is the easiest (and cheapest) one.

The Stigma Factor

One thing the CDC has been surprisingly vocal about lately is weight stigma. They’ve realized that shaming kids doesn't make them thinner; it makes them stressed. High cortisol levels from chronic stress—like being bullied at school—actually contribute to metabolic changes that make losing weight harder. It’s a vicious cycle.

The CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) have started aligning more closely on this. In 2023, the AAP released aggressive new guidelines suggesting that for some children, intensive lifestyle behavior intervention isn't enough. They even discussed medication and surgery for severe cases. The CDC monitors these outcomes because they need to see if these clinical interventions actually move the needle on a national level.

The Massive Gap in the Data

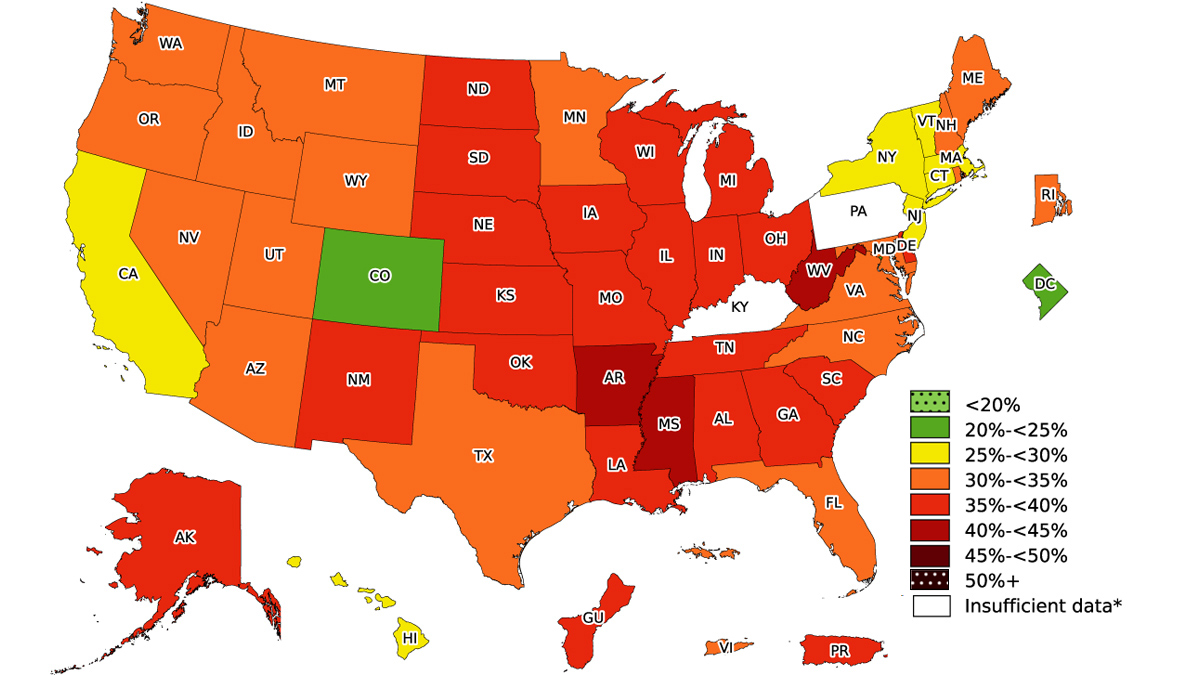

We have to talk about the disparities. The numbers for CDC and childhood obesity aren't distributed equally.

Among Hispanic children, the prevalence is around 26%. For Black children, it’s about 25%. Compare that to White children at 16% and Asian children at 9%.

📖 Related: Nuts Are Keto Friendly (Usually), But These 3 Mistakes Will Kick You Out Of Ketosis

Why?

Is it genetics? Rarely. Is it culture? Sometimes. Is it poverty? Mostly.

The CDC’s data shows a direct correlation between family income and obesity rates, but it’s not a straight line. In some higher-income brackets, obesity rates actually drop significantly for certain groups but stay high for others. This suggests that structural racism and systemic lack of investment in specific neighborhoods play a massive role. You can't out-run a lack of grocery stores.

Practical Steps for Real Change

If you are a parent, an educator, or just someone tired of seeing these stats rise, the CDC’s research points toward a few high-impact areas that actually make a difference. These aren't just "tips"—they are evidence-based pivots.

1. Focus on "Active People, Healthy Nation."

This is a CDC initiative aimed at getting 27 million people more active by 2027. For kids, this means advocating for "Safe Routes to School." If your school doesn't have a walking bus or a safe bike path, that is a policy failure, not a parenting failure.

2. The 12:00 AM Rule.

Sleep is the most underrated factor in childhood obesity. The CDC highlights that insufficient sleep triggers hormones like ghrelin (which makes you hungry) and suppresses leptin (which tells you you're full). A tired kid is a hungry kid. Fix the sleep, and you often fix the snacking.

3. Water as the Default.

The CDC’s "Rethink Your Drink" campaign isn't just about soda. It’s about juice boxes, sports drinks, and flavored milks. Most kids are drinking their daily sugar limit before lunch. Switching the default to water in schools and at home is the single fastest way to reduce empty calorie intake without a kid feeling "deprived."

👉 See also: That Time a Doctor With Measles Treating Kids Sparked a Massive Health Crisis

4. Community Advocacy.

Look at your local zoning laws. Seriously. The CDC provides toolkits for "Complete Streets" policies. These ensure that when a road is built, it includes sidewalks and bike lanes. If you want to fight childhood obesity, go to a city council meeting and ask for a crosswalk.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The CDC and childhood obesity relationship is evolving. We are moving away from the era of "Let's Move" and into an era of "Let's Rebuild."

It’s clear that individual effort isn't enough to fight a global shift in how food is processed and how cities are designed. The CDC’s role is to provide the data that proves we need bigger changes. They are currently tracking the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on childhood weight gain, which saw a significant "BMI rebound" as kids were stuck indoors and stress levels skyrocketed.

The goal isn't to make every kid thin. The goal is metabolic health. It's about preventing Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure in teenagers—things we used to only see in 60-year-olds.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Check the CDC’s "Data, Trends, and Maps" tool. It’s an interactive way to see exactly how your state is performing. If your state is lagging, email your representatives with those specific stats.

- Audit your "Micro-Environment." Instead of a diet, look at your kitchen counter. If the first thing a kid sees is fruit, they’ll eat it. If it’s a box of crackers, they’ll eat those.

- Support School Wellness Committees. Every school district that participates in federal meal programs is required to have a local school wellness policy. Most parents don't even know these committees exist. Join one. You can influence the vending machine contracts and the amount of recess time.

- Consult the CDC’s BMI Percentile Calculator. If you’re worried, use the official tool to get a baseline, but then take that data to a pediatrician. Don't try to "diet" a child without medical supervision, as it can interfere with necessary growth spurts and bone density development.

The data is clear, even if the solution is hard. We have to change the world around the child, because the child is just responding to the world we built.