He’s a phoney. You’re a phoney. Everything is just one big, depressing mess of phoneiness.

If those words don't immediately conjure up the image of a slouching teenager in a red hunting hat, you probably skipped high school English. Or maybe you just have a better social life than the rest of us. Published in 1951, The Catcher in the Rye remains one of the most polarizing artifacts in American literature. Some people find Holden Caulfield to be a relatable icon of teenage angst. Others think he’s a whiny, privileged brat who needs a job and a reality check. Honestly? Both sides are right.

J.D. Salinger didn't set out to write a "Young Adult" novel. The term barely existed back then. He wrote a story about a kid suffering from what we would now likely diagnose as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and clinical depression. But because it’s told through the voice of a cynical sixteen-year-old, it’s often dismissed as a "phase." It isn't just a phase. It's a brutal, honest look at what happens when a person realizes that growing up means losing your innocence.

The Catcher in the Rye and the Myth of the "Whiny Teenager"

Why do people hate Holden?

Seriously, if you look at Goodreads reviews or TikTok book discussions, the vitriol is intense. People call him "insufferable." They hate that he’s wealthy but miserable. They hate that he flunks out of Pencey Prep. But here is the thing: Holden is grieving. Most people forget that the entire backbone of The Catcher in the Rye is the death of Holden’s younger brother, Allie.

Allie died of leukemia. Holden broke his hand punching out the windows of the garage because he didn't know how to handle the rage. He’s physically and mentally scarred. When he wanders around New York City for three days, he isn't just "playing hooky." He’s having a nervous breakdown.

The title itself comes from a mistake Holden makes. He hears a kid singing a poem by Robert Burns, Comin' Thro' the Rye. He misinterprets the lyrics. He imagines a field of rye where thousands of little kids are playing, and he’s standing on the edge of a "crazy cliff." His only job is to catch any kid who gets too close to the edge. He wants to save them from falling into the "adult" world. He wants to stop time.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

It’s a beautiful, desperate, and completely impossible goal.

Salinger’s Own Trauma

You can’t talk about this book without talking about Jerome David Salinger. He was a veteran. He landed on Utah Beach on D-Day. He carried the first six chapters of The Catcher in the Rye with him during the war. Think about that for a second. While he was literally dodging bullets and witnessing the horrors of the Holocaust (he was among the first soldiers to enter a liberated concentration camp), he was writing about Holden Caulfield.

Salinger’s daughter, Margaret, once wrote about how her father couldn't handle loud noises or sudden movements. He lived his life in a sort of self-imposed exile in Cornish, New Hampshire. When you read the book through the lens of Salinger’s own war trauma, Holden’s obsession with "phonies" feels less like teenage rebellion and more like a rejection of a society that can pretend everything is "grand" while the world burns.

Why It Was Banned (And Why That’s Kind of Silly Now)

For decades, this was the most frequently banned book in U.S. schools. Why?

- The Language: Holden says "goddam" and "hell" a lot.

- The Prostitution Scene: The awkward encounter with Sunny the prostitute and Maurice the pimp.

- The "Negative" Influence: Parents feared kids would emulate Holden’s rebellion.

By 2026 standards, the "scandalous" parts of the book feel almost quaint. We have HBO shows that make Holden’s weekend in New York look like a trip to Disneyland. But the bans kept the book alive. Nothing makes a teenager want to read a book more than a school board saying they aren't allowed to.

The Mark David Chapman Connection

We have to address the elephant in the room. This book has a dark association with real-world violence. Mark David Chapman was carrying a copy of The Catcher in the Rye when he murdered John Lennon in 1980. He even wrote "This is my statement" inside the cover and signed it "Holden Caulfield."

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

John Hinckley Jr., who tried to assassinate Ronald Reagan, also had the book in his hotel room.

This led to a weird urban legend that the book was some kind of "trigger" for "lone wolf" killers. In reality, these were deeply disturbed individuals who projected their own fixations onto a character who felt isolated. Holden himself is actually very non-violent. He talks a big game, but he’s terrified of confrontation. He’s a pacifist who can’t even win a fight with his own roommate.

The Misconception of "The Phoney"

Holden calls everyone a phoney. His brother D.B. is a phoney for writing for Hollywood. Sally Hayes is a phoney for liking the theater.

But if you read closely, Holden is the biggest phoney of them all. He lies constantly. He gives fake names to people on the train. He pretends to be older than he is so he can order drinks. This is the nuance people miss. Salinger isn't saying Holden is "right" and the world is "wrong." He’s showing a kid who is so terrified of being vulnerable that he uses "phoniness" as a shield to keep people at a distance.

If he hates everyone, then it doesn't hurt so much when they leave him.

The Ending: What Actually Happens?

The book ends in a sanitarium—or at least, some kind of psychiatric facility in California. Holden is "taking it easy" and talking to a doctor. He’s not cured. He’s just... there.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

The final scene with his sister Phoebe on the carousel is the only moment of pure joy in the book. He watches her reach for the "gold ring." He realizes that you have to let kids reach for it, even if they might fall. You can't be the catcher in the rye. It’s a moment of surrender.

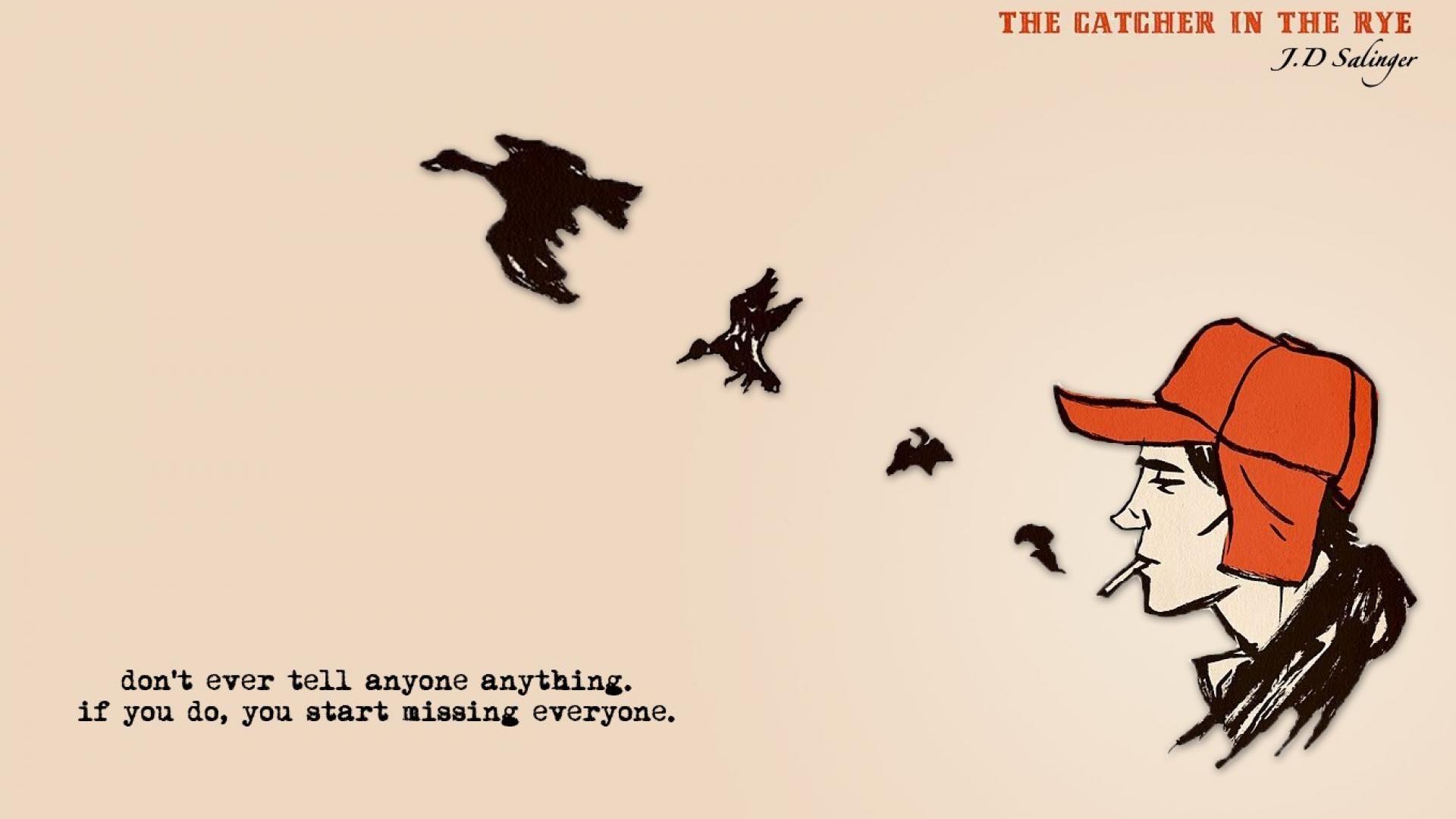

He ends the book by saying, "Don't ever tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody."

It’s one of the loneliest lines in literature.

How to Re-Read Catcher in the Rye Today

If it’s been ten years since you read it, or if you only read it because you had to pass a quiz, try it again with these perspectives:

- Look for the Allie references. Every time Holden gets depressed, Allie is nearby in his thoughts. The book isn't about school; it's about grief.

- Ignore the slang. Yes, the "kills me" and "and all" can be annoying. Read past it. Focus on the rhythm of his anxiety.

- Watch the adults. Most of the adults in the book actually try to help him. Mr. Spencer, the nuns at the diner, even Mr. Antolini (despite the ambiguous "creepy" scene). Holden rejects them because he’s not ready to be helped.

- Identify the "Museum of Natural History" moments. Holden loves the museum because nothing ever changes there. In a world where people die and friends grow up, the glass cases are the only things he can trust.

Practical Insight: If you're struggling with feelings of isolation or the "phoniness" of modern social media culture, The Catcher in the Rye is actually a great companion. It reminds us that the feeling of "not fitting in" isn't a modern invention—it’s a fundamental part of being human.

Instead of looking at Holden as a character to emulate, look at him as a cautionary tale about what happens when you refuse to let go of the past. To move forward, you have to stop trying to catch everyone in the rye and start figuring out how to walk through it yourself.

Pick up a physical copy. Avoid the e-book if you can. Salinger famously hated the idea of his work being digitized or having cover art (which is why most copies are just plain white or maroon). Experience the story the way he intended—just you and the voice of a kid who just wanted someone to listen.