Lee Strobel was a man who lived by the facts. As the legal editor for the Chicago Tribune, his world was built on a foundation of evidence, cross-examination, and the cold, hard logic of a courtroom. He was an atheist. A committed one. So, when his wife, Leslie, announced she had become a Christian in 1979, Strobel didn't just get annoyed. He got clinical. He decided to use his journalistic chops to debunk the entire foundation of the Christian faith. He wanted his wife back, and he figured the best way to do that was to prove that the Resurrection was a fairy tale.

The result of that two-year obsession was The Case for Christ book, first published in 1998. It didn't just sell; it became a cultural phenomenon that essentially defined a specific genre of modern Christian apologetics.

What Actually Happens in The Case for Christ Book?

Strobel approaches the project like a beat reporter. He doesn't just sit in a library reading dusty commentaries. Instead, he travels across the country to interview thirteen different scholars. These aren't just local pastors; they are people with PhDs from places like Cambridge, Princeton, and Brandeis.

He structures the book into three main "files": the Record, the Profile, and the Evidence.

In the first section, he digs into the reliability of the New Testament. He talks to Dr. Craig Blomberg about whether the biographies of Jesus can actually be trusted. They discuss things like the "Q" document and the dates the Gospels were written. Strobel asks the "gotcha" questions you'd expect from a skeptical journalist. Are the copies we have accurate? Did the writers have a bias that clouded their reporting?

Then, he moves into the psychological and medical side of things. One of the most famous chapters involves an interview with Dr. Alexander Metherell. They go into gruesome, clinical detail about the crucifixion. The goal here is to debunk the "Swoon Theory"—the idea that Jesus didn't actually die on the cross but just fainted and woke up later in the cool air of the tomb. Metherell’s medical breakdown of hypovolemic shock and asphyxiation is, honestly, hard to read if you have a weak stomach.

Finally, he tackles the "Smoking Gun"—the empty tomb. He interviews Dr. William Lane Craig, a heavyweight in philosophy and theology. They walk through the historical "facts" that even many secular scholars agree on, like the discovery of the tomb by women and the sudden transformation of the disciples from cowards into martyrs.

👉 See also: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Why People Are Still Talking About It Decades Later

You might think a book from the late 90s would be irrelevant by now. It’s not. The Case for Christ book continues to be a massive gateway for people questioning their faith or looking for intellectual grounding.

Part of the appeal is the narrative. It’s a detective story. Strobel plays the role of the cynical investigator, which makes the reader feel like they are part of the process. He isn't preaching at you; he's inviting you to look at the "exhibits" with him.

However, the book isn't without its critics. A lot of them.

Secular skeptics and even some liberal Christian scholars point out that Strobel only interviewed people who already agreed with his eventual conclusion. He didn't sit down with Bart Ehrman or other prominent critics of the New Testament’s reliability. Critics argue that while the scholars he interviewed are highly credentialed, the book represents a "one-sided trial." It’s like a prosecutor presenting a case without a defense attorney in the room.

Strobel’s defense to this has usually been that he was a skeptic himself, and he was asking the questions that skeptics ask. But in the world of academic history, the "Case" he builds is seen by some as a curated selection of evidence rather than an exhaustive look at all perspectives.

The Scientific and Historical Friction

One of the big sticking points in the The Case for Christ book is the handling of the "shroud of Turin" or the specific timing of the census of Quirinius. These are areas where historical data is messy.

✨ Don't miss: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Take the "Circumstantial Evidence" chapter. Strobel talks about the "shroud of witnesses." He pushes on the idea that 500 people seeing a risen Jesus at once couldn't have been a mass hallucination. Skeptics like Richard Carrier have written extensively countering these points, suggesting that the "500" mentioned in 1 Corinthians 15 might be a theological claim rather than a verifiable historical report.

Yet, for many readers, the sheer volume of "concessions" from the secular world that Strobel highlights—like the fact that the tomb was indeed empty—is enough to shift the needle. It's about the cumulative weight of the evidence rather than any one single piece.

It’s Kinda More Than Just a Book Now

The impact of the book was so large it spawned a whole "Case for..." franchise. There’s The Case for Faith, The Case for a Creator, and even The Case for Christmas.

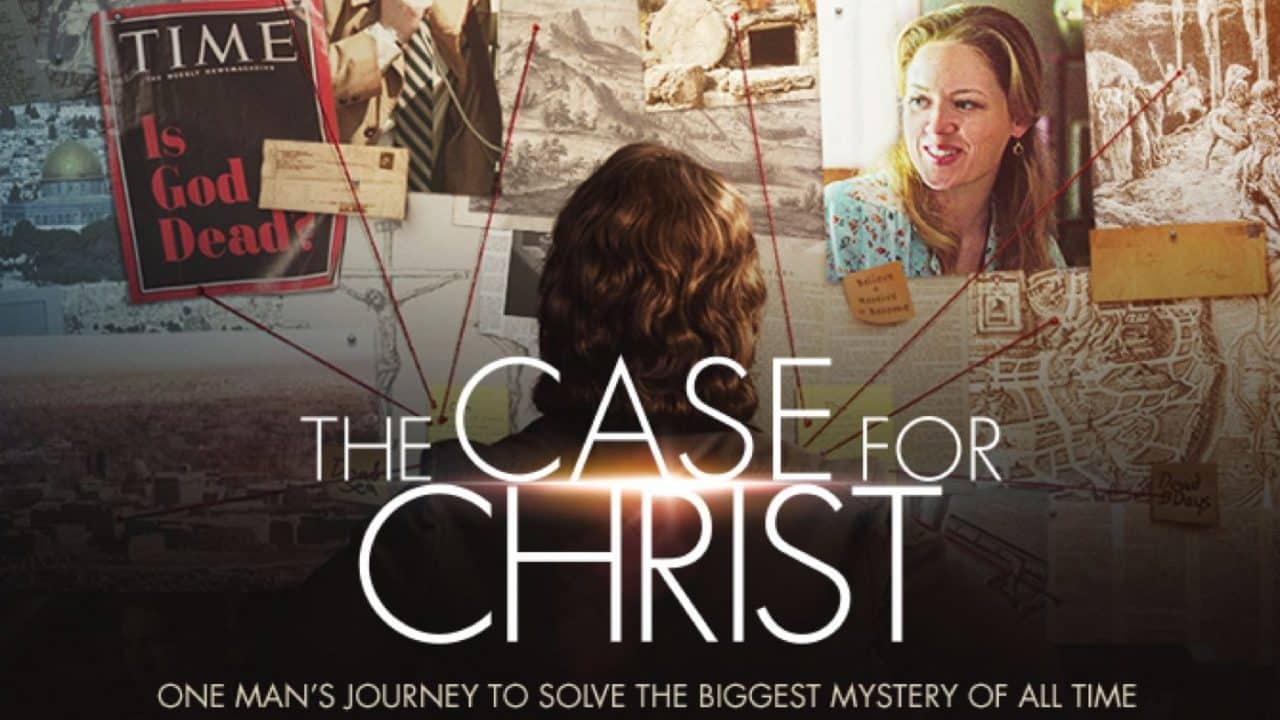

In 2017, they turned it into a major motion picture. It was a decent hit, especially in the faith-based film market. Seeing Mike Vogel play a 1980s Lee Strobel with a massive mustache really drove home the personal stakes of the story. It wasn't just a theological debate; it was a marriage on the brink of collapse because of a fundamental disagreement about reality.

The Nuance of the "Journalistic" Approach

Is Strobel really being objective? Probably not in the way a modern scientist would define it. He’s writing from the perspective of a convert. He already knows how the story ends. But his background at the Tribune gives the writing a crispness that you don't often find in religious literature. He knows how to pace a story. He knows how to explain complex Greek linguistic concepts without making your eyes glaze over.

He deals with the "Criteria of Embarrassment"—the idea that if you were making up a story to start a religion, you wouldn't make your main hero get executed as a criminal or have women (whose testimony wasn't legally valid at the time) be the first witnesses to the resurrection. These are the "oddities" of history that Strobel leans into.

🔗 Read more: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Does the Evidence Actually Hold Up?

If you pick up The Case for Christ book today, you have to realize that scholarship has moved forward. Since 1998, we’ve seen the rise of the "New Atheism" movement and its subsequent decline. We’ve had massive discoveries in archaeology and more nuanced debates about the "Historical Jesus."

Some of the arguments Strobel uses are "minimal facts" arguments. This is a strategy popularized by Gary Habermas (who is interviewed in the book). The idea is to only use facts that are granted by the vast majority of scholars, including the skeptical ones.

- Jesus died by crucifixion.

- The disciples believed they saw him alive.

- The skeptic James (Jesus’ brother) was converted.

- The persecutor Paul was converted.

Strobel argues that the best explanation for these "facts" is a literal resurrection. Others argue for a legendary development or a subjective visionary experience. The book doesn't necessarily "solve" the debate, but it draws the battle lines very clearly.

What You Should Do If You're Planning to Read It

If you are curious about the historical claims of Christianity, this is basically required reading, whether you end up agreeing with it or not. It’s a cultural touchstone.

Don't just read it in a vacuum. If you really want to test the "Case," read it alongside a critic. See how the arguments hold up when you look at the counter-points. Strobel’s writing is persuasive because it’s clear and punchy, but the topics he covers—manuscript evidence, ancient historiography, and the psychology of belief—are incredibly deep.

Practical Steps for Engaging with the Text:

- Check the sources. When Strobel cites a scholar like Bruce Metzger or Edwin Yamauchi, look up their actual academic work. The book is a "best of" summary; the real meat is in the textbooks those guys wrote.

- Focus on the "Why." Notice how Strobel focuses on the implications of the evidence. He’s not just interested in whether a guy named Jesus lived; he’s interested in whether that guy is who he said he was.

- Compare versions. There are updated editions of the book that address some of the newer archaeological finds. If you're buying a copy, get the one with the added "updates" to see how the arguments have evolved.

- Watch for the bias. Every writer has one. Strobel is open about his conversion, but watch how he frames the questions. Is he looking for the truth, or is he looking for a "win"? Deciding that for yourself is part of the reading experience.

The The Case for Christ book remains a powerhouse because it tackles the most important question in Western history with the urgency of a front-page deadline. It's a mix of memoir, investigative journalism, and legal brief. Whether it’s a "closed case" is up to you, but it’s a case that isn’t going away anytime soon.

To get the most out of the book, start with the chapters on "The Medical Evidence" and "The Fingerprint Evidence." These are usually the ones that stay with people the longest because they bridge the gap between abstract theology and physical, historical reality. From there, you can branch out into his more philosophical follow-ups or look into the critical responses from the secular community to get a full 360-degree view of the debate.