It started with a flash. On September 1, 1859, Richard Carrington, a wealthy brewery owner who spent his free time staring at the Sun through a telescope, saw something impossible. Two beads of white light suddenly intensified over a cluster of sunspots. They were so bright he thought his equipment was broken or a stray ray of light had leaked into his darkroom. It lasted five minutes.

That was the "white-light flare." It was the first time a human had ever witnessed a solar flare.

About 17 hours later—way faster than the usual three-to-four-day journey—the planet got hit. Hard. We call it the solar storm of 1859, or more commonly, the Carrington Event. Honestly, if it happened today, you wouldn't be reading this on your phone. You’d probably be looking for a flashlight and wondering why the grocery store's credit card reader just melted.

When the sky caught fire

The sheer scale of this thing is hard to wrap your head around. People in the Caribbean and Hawaii saw the Aurora Borealis. Think about that for a second. The Northern Lights, which usually require a trip to Iceland or Fairbanks, were visible from the tropics. In the Rocky Mountains, the light was so intense that gold miners woke up at 1:00 AM, thinking it was morning. They started making coffee and frying bacon.

The color wasn't just that eerie green we see in travel photos. It was blood red. Deep crimson. It pulsed.

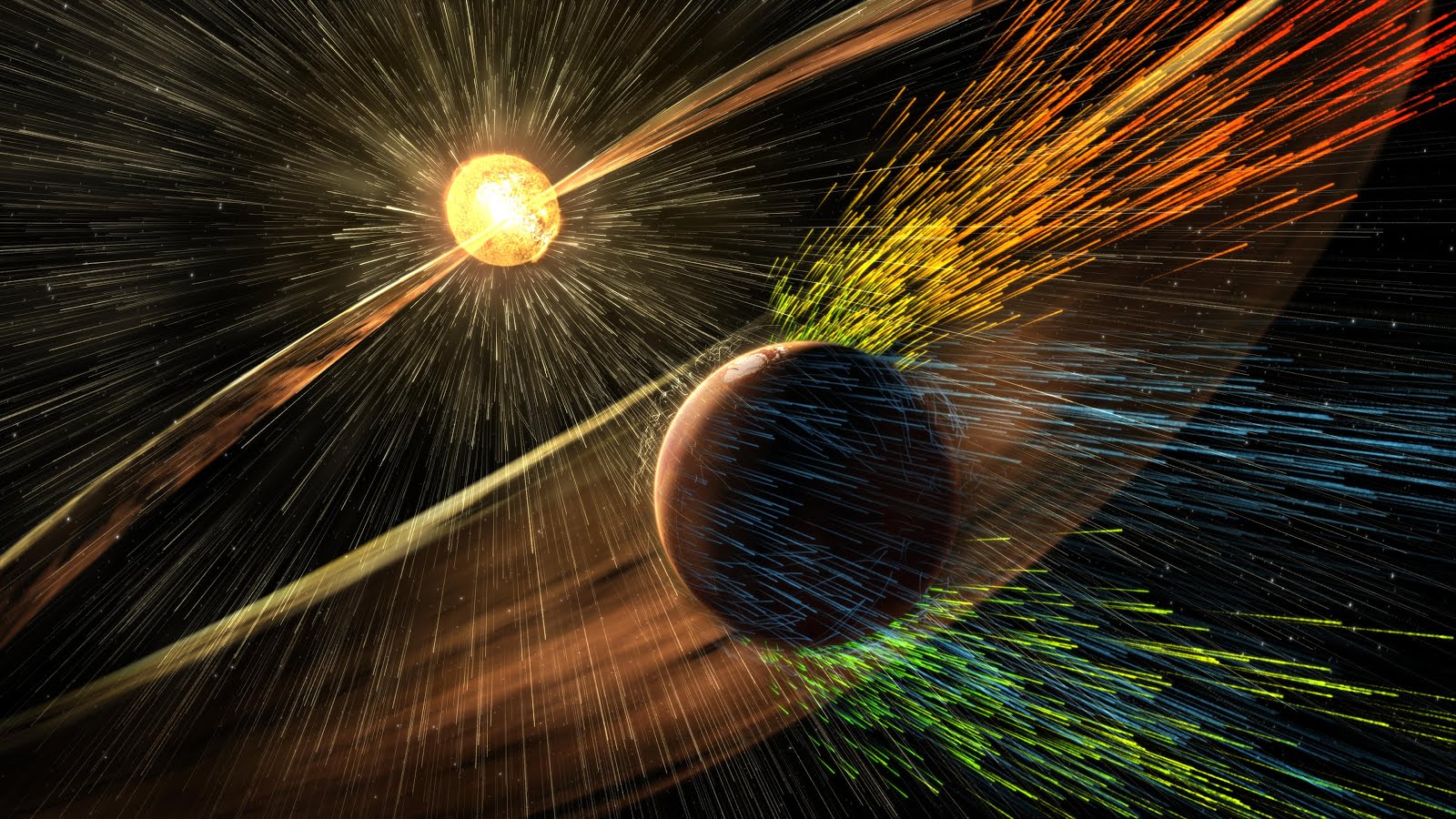

It wasn't just a light show, though. It was a massive injection of plasma and magnetic energy—a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME)—slamming into Earth's magnetosphere at millions of miles per hour. This created a geomagnetic storm of such magnitude that it remains the benchmark for "worst-case scenarios" in heliophysics today.

The Victorian Internet went into meltdown

In 1859, the only "high-tech" infrastructure we had was the telegraph. It was the Victorian internet. Miles and miles of copper wire stretched across continents.

When the solar storm of 1859 peaked, these wires turned into giant antennas. They sucked up the electrical energy from the atmosphere. Telegraph operators across Europe and North America reported sparks flying from their equipment. Some machines literally caught fire. Papers on the desks ignited.

💡 You might also like: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

The most famous story involves two operators: one in Boston and one in Portland, Maine. They realized the "natural" electricity in the lines was so strong they didn't even need their batteries. They disconnected their power sources and chatted for two hours using nothing but the energy provided by the solar storm. It sounds cool, but it was actually a terrifying sign of how vulnerable our technology had become.

Why this storm was "different"

Most solar storms are like a gentle breeze against a house. This one was a category five hurricane. The magnetic field of the CME was oriented "southward," which is basically the worst-case alignment. It meant the storm's magnetic field could easily merge with Earth's, pouring trillions of watts of power into our upper atmosphere.

Bruce Tsurutani, a retired plasma physicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, has spent decades analyzing the data we have from that era. While we didn't have satellites, we did have ground-based magnetometers. They went off the charts. Literally. The needles on the recording devices at the Greenwich Observatory in London swung so violently they broke or jumped off the paper.

Could our modern grid survive another 1859?

Probably not. At least, not without a lot of warning.

Basically, we have built a giant spiderweb of conductive metal over the entire planet since 1859. Our power grids, fiber optic cables, and satellite networks are all sitting ducks for a storm of this magnitude. In 1989, a much smaller storm knocked out the entire power grid in Quebec in 90 seconds. Six million people were in the dark for nine hours.

If the solar storm of 1859 hit today, the damage could be in the trillions of dollars. Lloyds of London estimated that a Carrington-class event could cost the U.S. alone up to $2.6 trillion.

The main problem isn't just the power going out. It's the transformers. These are the house-sized blocks of metal you see at substations. If a solar storm induces "geomagnetically induced currents" (GICs) into the grid, these transformers can melt. You can't just go to Home Depot and buy a replacement. They take years to build and require specialized transport. A multi-state blackout could last months, not days.

📖 Related: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

The Satellite Problem

We also have thousands of satellites now. In 1859, the sky was empty. Today, a Carrington-level event would likely fry the electronics on hundreds of communications and GPS satellites. Your phone's GPS wouldn't just be "glitchy"—it would be gone. This would ground flights, stop shipping, and mess with the timing of global financial transactions, which rely on GPS atomic clocks.

Misconceptions about solar flares

People often mix up solar flares and CMEs. They aren't the same thing.

A flare is a burst of light and X-rays. It reaches Earth in eight minutes. It messes with radio signals, but it doesn't cause the massive ground-level electrical surges. The CME is the physical cloud of plasma. That’s the "cannonball" that takes a day or two to arrive.

The solar storm of 1859 was a double-whammy because the flare was followed by an exceptionally fast CME. Most CMEs take 72 hours to reach us. This one arrived in 17.6 hours. That’s a speed of over 5 million miles per hour. We would have almost no time to react.

How we are preparing (or trying to)

Space weather is now a serious part of national security. Organizations like the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) in Colorado monitor the Sun 24/7. They look for "Active Regions"—sunspot groups that look like they're about to pop.

We have a few satellites, like the DSCOVR (Deep Space Climate Observatory), sitting at the L1 Lagrange point between the Earth and the Sun. It acts as a buoy. When a storm hits DSCOVR, we get about 15 to 60 minutes of "final warning" before the storm hits Earth.

It’s not much time.

👉 See also: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

Utility companies are starting to install "blocking devices" to prevent GICs from entering the grid, and they have protocols to "shed load" or take certain lines offline if a big one is coming. But honestly? It's a gamble. The grid is interconnected in ways we still don't fully control.

Future Outlook

The Sun goes through an 11-year cycle of activity. We are currently approaching "Solar Maximum" in the mid-2020s. This means more sunspots, more flares, and a higher chance of a big CME. Is another 1859 coming this year? Nobody knows. It’s like predicting when a massive earthquake will hit San Francisco. We know it will happen; we just don't know when.

Some researchers, like Dr. Pete Riley of Predictive Science Inc., have estimated the probability of another Carrington Event occurring within a decade at around 12%. That sounds low until you realize it’s basically a roll of an eight-sided die.

Actionable steps for the "Big One"

You don't need to be a doomsday prepper to be ready for space weather. Since the main risk is a long-term power outage, the advice is pretty much the same as preparing for a major hurricane or earthquake.

- Have a 72-hour kit: Water, non-perishable food, and a manual can opener. If the grid goes, the pumps that bring water to your house might stop too.

- Keep a physical radio: A battery-powered or hand-crank weather radio is vital. If the internet and cell towers go down, terrestrial radio might be the only way to get updates.

- Paper maps and cash: If GPS is down and digital payments are offline, you'll want a way to navigate and a way to buy supplies.

- Understand the "All Clear": Just because the sky looks normal doesn't mean the storm is over. Solar storms often come in "trains"—multiple CMEs hitting one after another.

The solar storm of 1859 was a reminder that we live in the atmosphere of a star. We are connected to it. We usually think of the Sun as a static, yellow ball that gives us light, but it’s a violent, magnetic beast. Our modern world is built on the assumption that this beast will stay quiet. History suggests otherwise.

Monitor current space weather conditions at the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center to see if any flares are currently heading our way. If you see a "G4" or "G5" alert, it's time to make sure your flashlights have fresh batteries.