Wichita is a quiet place. It’s the kind of city where people used to leave their back doors unlocked while they ran to the grocery store. But for thirty years, a shadow hung over the neighborhood of Park City and the surrounding suburbs. Everyone knew the name BTK. They knew what it stood for: Bind, Torture, Kill. For decades, the Wichita Kansas serial killer wasn't just a news headline; he was a ghost that lived in the periphery of every PTA meeting and church social.

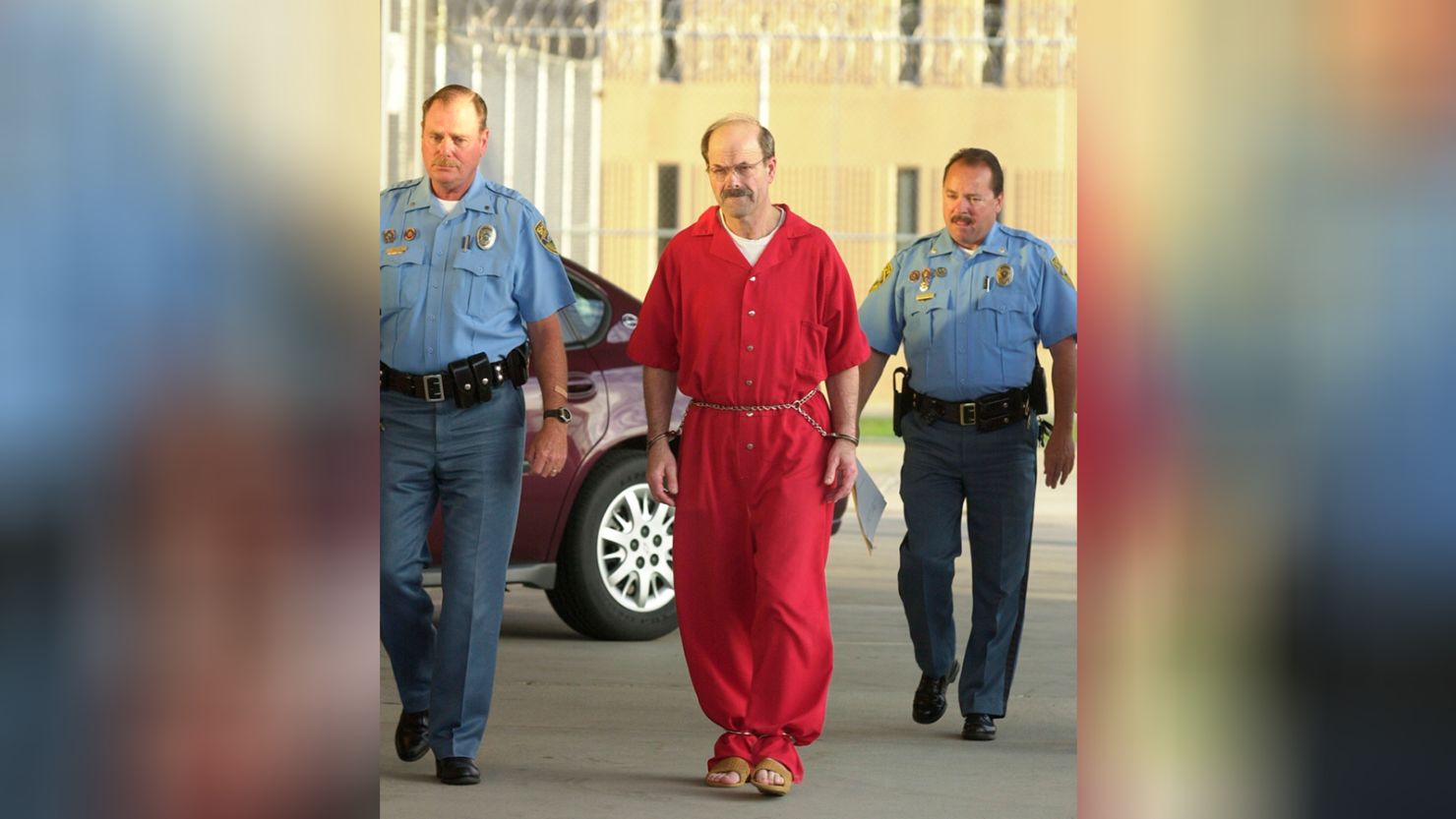

It’s honestly hard to describe the sheer level of paranoia that gripped the city in the 1970s. People weren't just scared. They were looking at their neighbors sideways. When Dennis Rader was finally arrested in 2005, the shock wasn't just that he had been caught. It was that he was a compliance officer. A Boy Scout leader. A president of his church council. He was exactly the person you’d trust to watch your house while you were on vacation.

The Otero Family and the Birth of a Nightmare

The horror began on January 15, 1974. Most people in Wichita can tell you exactly where they were when they heard about the Otero family. Joseph and Julie Otero, along with two of their children, were found murdered in their home. It was brutal. It was calculated.

This wasn't a crime of passion.

Rader later admitted he "targeted" them. He watched. He planned. He cut the phone lines. That’s a detail that still sends chills down the spines of true crime researchers—the cold, mechanical way he approached human life. He didn't just want to kill; he wanted the city to know he was doing it. He wanted the credit.

Shortly after the Otero murders, he left a letter in a book at the Wichita Public Library. This is where he gave himself the moniker. He literally wrote, "I will be called... B.T.K." He was his own publicist. It’s a classic trait of a narcissistic psychopath, but back then, the term "serial killer" wasn't even common parlance. The FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit was still in its infancy. Wichita was essentially the testing ground for modern criminal profiling.

A Decades-Long Game of Cat and Mouse

After the initial burst of violence in the 70s, which included the murders of Kathryn Bright, Shirley Vian, and Nancy Fox, the killer seemed to vanish. Or so people thought.

💡 You might also like: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

He didn't stop. He just got quieter.

He killed Marine Hedge in 1985 and Vicki Wegerle in 1986. Then, in 1991, he murdered Dolores Davis. But the communication stopped for a long time. By the late 90s, the Wichita Kansas serial killer was becoming a local legend—a "cold case" that younger generations only heard about in hushed tones. The fear had scabbed over.

Then came 2004.

The Wichita Eagle published a story on the 30th anniversary of the Otero murders. Rader, sitting in his office or his living room, couldn't handle being forgotten. He started sending letters again. He sent packages with trophies from his victims. He sent word puzzles. He was arrogant. Honestly, it was his own ego that eventually put the handcuffs on him.

The Floppy Disk That Ended It All

If you want to talk about the most famous blunder in criminal history, you have to talk about the purple 1.44MB floppy disk.

Rader was getting bold. He asked the police in a letter if he could communicate via floppy disk without being traced. He literally asked them for technical advice. The police, being smart, lied. They told him it would be fine. They said, "No, we can't trace that."

📖 Related: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

He believed them.

In February 2005, Rader sent a disk to KSAS-TV in Wichita. Within hours, forensic experts found a deleted file on the disk. The metadata pointed to "Christ Lutheran Church" and the last user was listed as "Dennis." A quick Google search (which was much simpler back then) showed that Dennis Rader was the president of the church council.

The police went to the church. They took his DNA from a pap smear his daughter had at a clinic—a controversial move at the time that stood up in court—and it was a match. The "ghost" of Wichita was a boring, middle-aged man who liked to power-trip over overgrown lawns and barking dogs.

Why the Case Remains Culturally Significant

You can't talk about Kansas history without this case. It changed the way the state views security and community. But it also changed how we understand the "mask of sanity."

Experts like Dr. Katherine Ramsland, who spent years interviewing Rader, point out that he was a "contained" killer. He didn't have a messy life. He was organized. This goes against the common misconception that serial killers are all "loners" living in basements. Rader was a family man. His wife and children had no idea. Imagine sitting down to dinner with a man who had spent his afternoon stalking a woman through a park. That’s the reality Wichita lived with.

Another thing people get wrong is the idea that he stopped because he "lost the urge."

👉 See also: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

He didn't.

Rader had "projects" lined up. He had a 10th victim in mind. He was active in his head every single day. The only thing that changed was his physical ability and his focus on his "legacy." He wanted to be in the history books alongside Ted Bundy and Jack the Ripper.

Practical Steps for Understanding the Legacy

If you’re researching the Wichita Kansas serial killer for historical or criminology purposes, you shouldn't just look at the gore. Look at the systemic failures and the eventual wins.

- Visit the Wichita Public Library archives. They hold the original clippings from the 70s. You can see the shift in the city's tone from "unfortunate tragedy" to "all-encompassing terror."

- Study the Forensic Science. The Rader case is a masterclass in digital forensics. Understanding how metadata works today starts with understanding how a deleted Word file on a floppy disk caught a killer in 2005.

- Read "Confession of a Serial Killer" by Katherine Ramsland. It’s the most authoritative look into his psyche, though it’s a tough read. It’s based on direct correspondence with Rader.

- Evaluate the ethics of DNA collection. The use of a relative's medical records to catch Rader set a massive legal precedent. Research the "familial DNA" debates that continue today with cases like the Golden State Killer.

The BTK case isn't just a "true crime" story. It’s a case study in how a community survives a predator in its midst. It reminds us that evil doesn't always look like a monster. Sometimes, it looks like the man checking your fence height or the guy sitting in the pew behind you, singing the loudest.

Wichita is safer now, but the scars are permanent. The city no longer leaves its back doors unlocked. That’s the lasting footprint Dennis Rader left on the plains. It’s a heavy lesson in vigilance and the reality that some secrets can be kept for a lifetime, but eventually, the metadata always tells the truth.