It was a Wednesday. May 30, 1431, to be exact. The air in Rouen, Normandy, was probably thick with that damp, salty English Channel mist, but by mid-morning, all anyone could smell was smoke. Imagine being nineteen years old and facing down a pile of wood taller than you are, knowing you're about to be the center of a very public, very painful execution. That’s exactly what happened. When people ask when was joan of arc killed, they’re usually looking for a date to plug into a history quiz, but the "when" is so much more than a timestamp on a calendar. It was the climax of a messy, politically charged circus that still makes modern lawyers cringe.

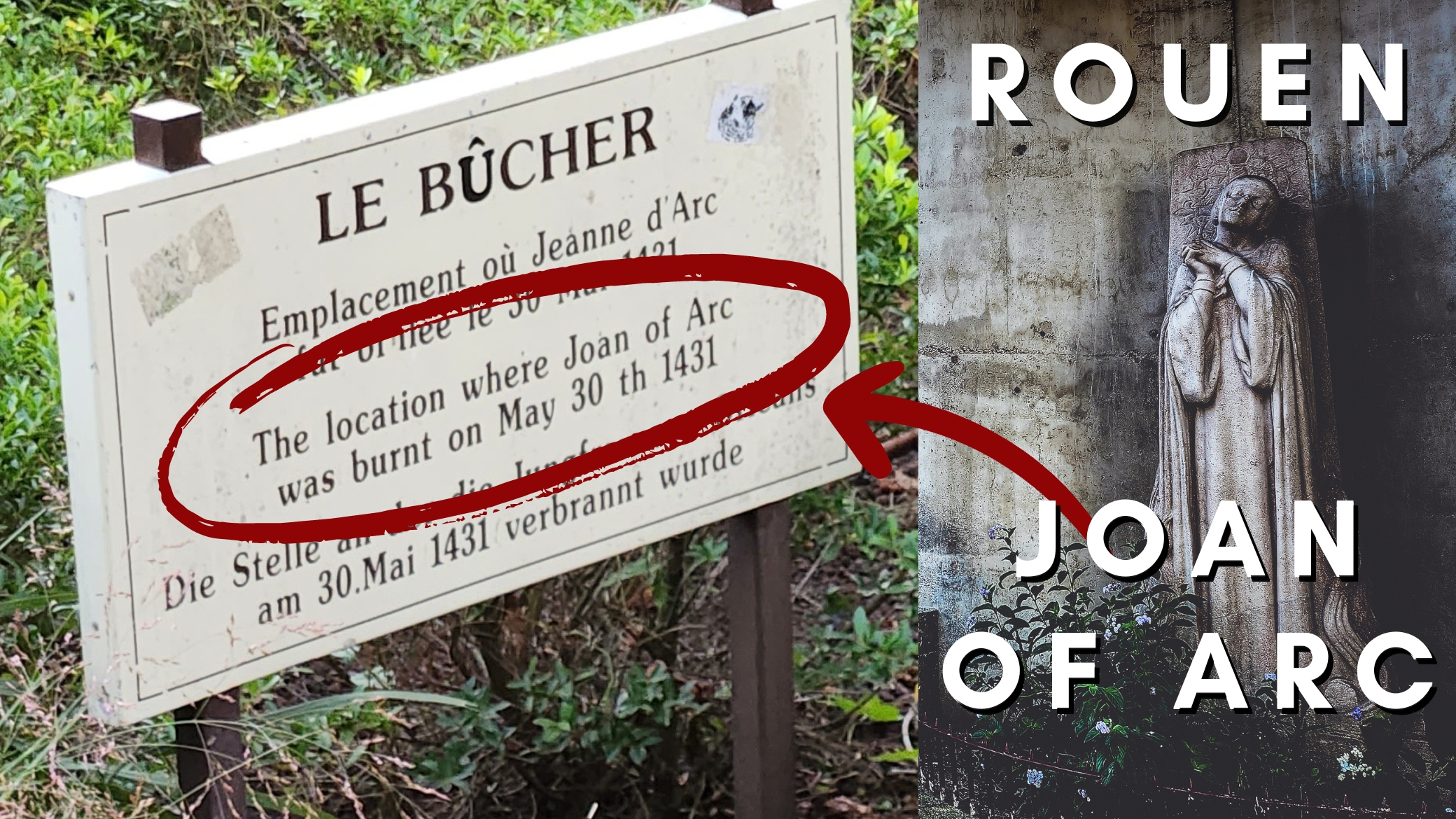

She died in the Old Market Square.

Rouen wasn't just some random village. It was the seat of English power in France at the time. If you’ve ever been there, you know the spot is now marked by a surprisingly modern, almost space-age church, but back then? It was a theater of cruelty. Joan was led out at about 9:00 AM. She wore a long shift. They put a paper cap on her head—a "mitre"—that labeled her with words like "heretic," "relapsed," and "idolater." It was psychological warfare.

The Logistics of a 15th-Century Execution

The execution wasn't a quick affair. It was a spectacle. The English were terrified of her, honestly. They didn't just want her dead; they needed her erased. They needed to prove she wasn't sent by God, because if she was, then the English King was fighting against Heaven itself. That’s a bad look for a monarch.

Geoffroy Thérage was the executioner that day. Records suggest he was actually pretty shaken by the whole thing. He had to build the pyre unusually high. Why? Because the English wanted everyone in the crowd—and there were thousands—to see her face as the flames rose. They didn't want any "she escaped" rumors starting up later. But this backfired. Because the pyre was so high, the executioner couldn't reach her to perform a "mercy kill" or use any tricks to speed up the process. She felt everything.

She asked for a cross. An English soldier, moved by the sight of a teenager shaking in fear, tied two sticks together and gave them to her. She tucked them into her dress. Then, a friar named Isambart de la Pierre ran to a nearby church to get a real processional crucifix. He held it up high so she could see it through the smoke.

Why the Timing of May 1431 Matters

You have to look at the Hundred Years' War context to understand why when was joan of arc killed is such a pivotal question. The year 1431 was a desperate time for the English. They had just lost Orléans. They had seen the "Dauphin" crowned as Charles VII in Reims. Their grip on France was slipping like wet soap.

👉 See also: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

If Joan had been captured and killed in 1428, she would have been a footnote. If she had survived until 1450, she might have been a retired general. But dying in 1431 made her a permanent martyr at the exact moment the French national identity was being born.

The Trial That Wasn't Really a Trial

The "when" is also tied to the "how long." She was in a cage for months before the fire. From her capture at Compiègne in May 1430 to her death a year later, she was subjected to constant interrogation. This wasn't a fair fight. Pierre Cauchon, the Bishop of Beauvais, was the guy running the show. He was firmly in the English pocket.

They tried to trap her with theological questions that would trip up a PhD student today.

- They asked if she was in a "state of grace."

- If she said yes, she was being arrogant (a sin).

- If she said no, she was admitting she was a fraud.

- Her answer? "If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me."

Basically, she outsmarted a room full of bitter old men. That’s part of why they killed her. She was making them look incompetent.

What Actually Happened in the Old Market Square?

When the fire started, she didn't scream for revenge. She didn't curse the English. She shouted "Jesus" over and over. It was so intense that some of the English soldiers reportedly started crying. One secretary to the English King, Jean de Tressart, supposedly walked away saying, "We are lost, for we have burned a saint."

He wasn't wrong.

✨ Don't miss: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

But the English were thorough. After she died from smoke inhalation and the flames, they actually paused the fire. They pulled back the wood to show the crowd her charred body so no one could claim she had magically flown away. Then, they burned the remains twice more. They wanted nothing left. No bones for relics. No hair. No clothes. They gathered up her ashes and dumped them into the Seine River from the Mathilda Bridge.

Misconceptions About the Date and Manner of Death

A lot of people think she was burned for witchcraft. Technically? No. The official charge was "relapsed heresy."

Here is the weird part: The main evidence they used to "prove" she had relapsed was that she put her male clothes back on in prison. She had promised to wear women's dresses, but in a cell full of aggressive male guards, she went back to her soldier's tunic and hosen for protection. The judges called this a "relapse" into heretical behavior. It was a legal loophole used to justify a political execution.

Also, let's talk about the "voices." People today love to diagnose her with everything from schizophrenia to bovine tuberculosis. But in 1431, the timing of her death was based on the belief that those voices were demonic. Whether you believe she heard saints or just had a very active imagination, the result was the same. The "when" was determined by when the English finally felt they had enough "legal" cover to light the match.

The Long Road to Rehabilitation

If you think 1431 was the end of the story, you're missing the best part. About twenty years later, the war was basically over, and the French had won. Charles VII, the guy Joan helped crown, realized it looked kind of bad that a "heretic" had put the crown on his head. He ordered a retrial.

In 1456, the Pope's commission looked at the 1431 proceedings and basically said, "Yeah, this was garbage." They overturned the verdict. They declared her a martyr. But it took until 1920—nearly 500 years after she was killed—for the Catholic Church to actually canonize her as a saint. Talk about a slow bureaucracy.

🔗 Read more: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

Why We Still Care

Honestly, the story of when was joan of arc killed resonates because it's the ultimate "power vs. truth" narrative. You have a peasant girl with no education who changed the map of Europe. She was killed because she was inconvenient to the status quo.

When you look at the timeline, it's a reminder of how quickly "justice" can be weaponized. The trial started in February. She was dead by May. In the Middle Ages, that was a lightning-fast legal process.

Tangible Ways to Connect with this History

If you're a history buff or just someone who likes a good underdog story, you don't have to just read about it.

- Visit Rouen: The Historial Jeanne d’Arc is an immersive museum built into the old archbishop’s palace where part of her trial actually happened. It’s not your dusty, old-school museum; it uses digital projections to walk you through the trial.

- Read the Trial Transcripts: You can find translated versions of the actual questions and her actual answers. Seeing her wit on paper makes her feel like a real person, not a stained-glass window.

- Check out the Cinema: From the 1928 silent masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc (which focuses almost entirely on the day she was killed) to more modern takes, the "when" of her death has been visualized a hundred different ways. The 1928 version is particularly haunting because it uses actual records from the trial for the dialogue.

The death of Joan of Arc wasn't just an execution; it was a failure of the legal system and a turning point for France. She was killed on May 30, 1431, but in a weird way, that was the day she became immortal. If you ever find yourself in Rouen, go to the market square. Look at the giant cross they have there now. It’s exactly where the pyre stood. It’s a quiet spot now, mostly surrounded by cafes and shops, but if you stand there long enough, you can almost hear the echoes of 1431.

To truly understand this event, you should look into the "Nullification Trial" of 1456. It provides the counter-testimony from her childhood friends and the soldiers who served with her, offering a much more human side to the girl who died in the flames. You can also research the "Cross of Rouen," which marks the site of the execution and serves as a somber reminder of the events of that May morning.