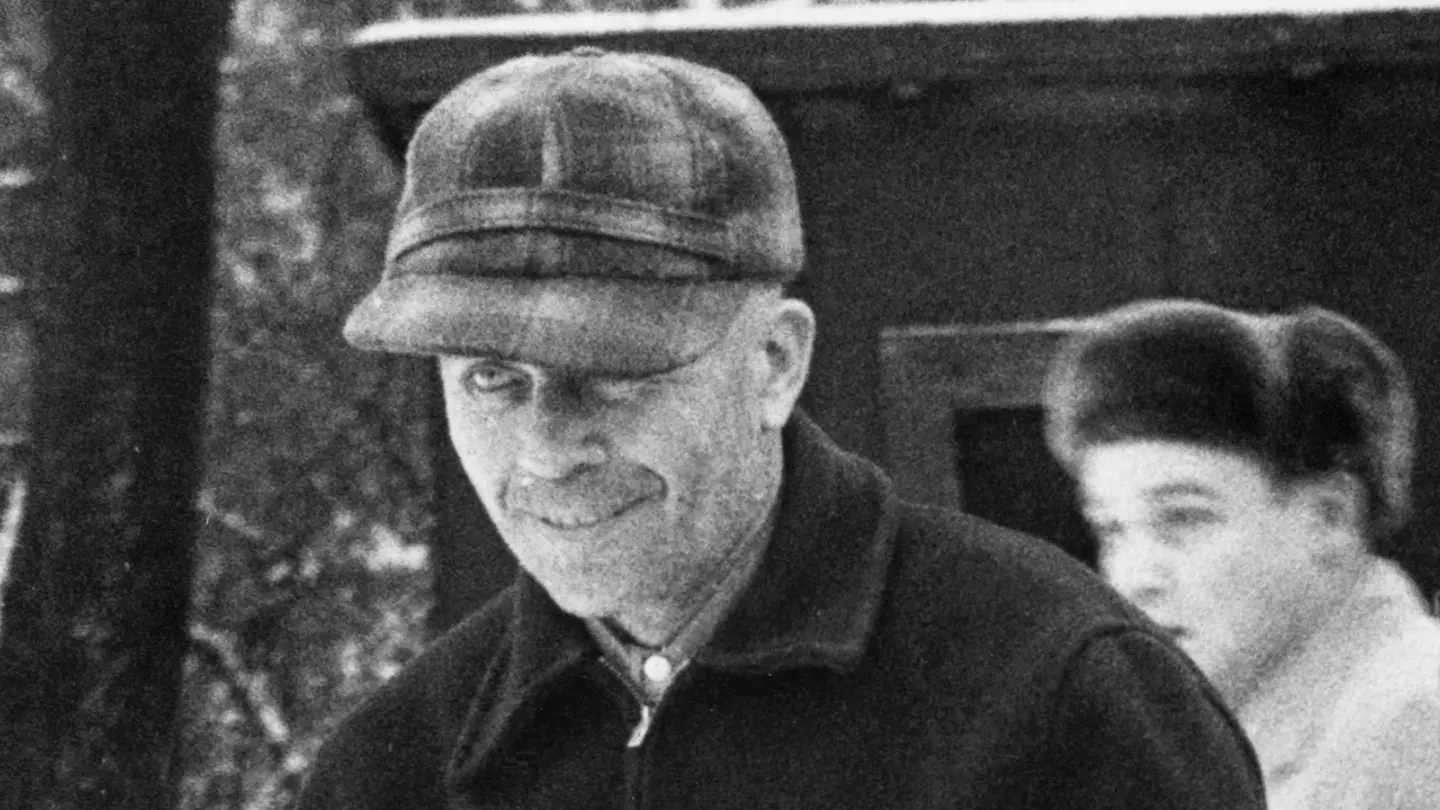

Plainfield, Wisconsin, used to be just another quiet spot on the map. Then 1957 happened. When police walked into the farmhouse of Edward Theodore Gein, they weren't looking for a museum of horrors; they were looking for a missing hardware store owner named Bernice Worden. What they found instead changed the American psyche forever. Among the masks made of skin and chairs upholstered with human remains, the discovery of Ed Gein’s preserved vulvas remains one of the most jarring, clinical examples of his specific psychosis.

He was a quiet man. Odd, sure. But nobody thought he was a monster.

The items found in that house weren't just trophies of a killer. They were the physical manifestations of a man trying to literally crawl inside the identity of his deceased mother, Augusta. Gein didn't just kill; he curated. He was a grave robber who became a seamstress of the macabre. The sheer volume of biological material recovered—including a box containing nine salted, dried vulvas—points to a fixation that goes far beyond simple murder. It’s about the total erasure of the self and the desperate, failed attempt to become someone else through biology.

Why the Plainfield Ghoul Collected These Remains

Gein’s pathology is a messy, dark web of grief and repression. After his mother died in 1945, his world basically ended. He was alone in a house that felt like a tomb, so he decided to make it one. He started visiting local cemeteries. He wasn't looking for jewelry or valuables. He was looking for bodies that resembled his mother.

The collection of Ed Gein’s preserved vulvas was part of what he called his "woman suit." He told investigators he wanted to create a complete costume made of human skin so he could step into it and, in a way, bring his mother back to life. It sounds like something out of a low-budget slasher flick, but for Gein, it was a practical solution to an unbearable loneliness.

He didn't just hack things apart. He used salt to preserve the tissue, a technique he likely picked up from his years of hunting and dressing deer. Some of the remains were kept in a shoebox, while others were part of larger "garments." When you look at the forensic reports from the Wisconsin State Crime Lab, the level of detachment Gein showed is terrifying. He treated human anatomy like fabric. He was a craftsman of the dead.

💡 You might also like: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

The Psychological Profile of a Grave Robber

Most people assume Gein was a prolific serial killer. He wasn't. He only officially killed two people: Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden. The rest of his "materials" came from the ground. He admitted to making dozens of late-night trips to three different Plainfield cemeteries. He’d dig up the bodies of middle-aged women, haul them back to his kitchen, and get to work.

The presence of the Ed Gein preserved vulvas specifically highlights his gender dysphoria and extreme maternal fixation. Psychologists like Dr. George Arndt, who interviewed Gein, noted that he wasn't necessarily a "sexual" killer in the traditional sense. He didn't rape his victims. He wanted to be them. The preservation of the female genitalia was a key component of this transformation. He wanted the physical markers of womanhood to be part of his own body.

Imagine the scene. A cold, cluttered farmhouse. No electricity in most of the rooms. And Gein, sitting there by the light of a lamp, meticulously salting human skin. It’s a level of depravity that defies easy explanation. Honestly, it’s why he remains the primary inspiration for characters like Norman Bates, Leatherface, and Buffalo Bill. He provided the blueprint for the cinematic "weirdo" killer, but the reality was much more pathetic and tragic than the movies suggest.

The Forensic Reality of the 1957 Search

When Sheriff Art Schley entered the Gein house, the smell must have been unbelievable. It wasn't just the smell of death; it was the smell of a house that hadn't been cleaned in a decade. They found a wastebasket made of human skin. They found skulls on his bedposts. But the small, preserved pieces of anatomy were what truly shocked the veteran officers.

The Ed Gein preserved vulvas were found alongside other "apparel" items, including a belt made of nipples and a pair of leggings made from the skin of human legs. The police inventory is a long, nauseating list of household items turned into biological nightmares. Gein was surprisingly cooperative during questioning. He didn't scream or deny it. He just explained, in his soft, high-pitched voice, how he did it. He spoke about his "shrine" to his mother—the rooms he had boarded up to keep them exactly as they were when she was alive.

📖 Related: What Category Was Harvey? The Surprising Truth Behind the Number

It’s important to realize that Gein didn't see himself as a villain. He saw himself as a man with a hobby. That’s the scariest part. He was a "handyman" who applied his skills to the only thing he had left—the dead.

Impact on Modern Criminology and Pop Culture

We are still obsessed with this case for a reason. Gein is the "OG" of true crime. Before him, the public didn't really grasp that a person could look totally normal while keeping a box of Ed Gein’s preserved vulvas in their pantry. He shattered the illusion of small-town safety.

His case led to massive shifts in how we handle the "criminally insane." Gein was eventually found unfit to stand trial and spent the rest of his life in state hospitals, mostly at the Mendota Mental Health Institute. He was described as a model patient. He was gentle, helpful, and never caused trouble. This contrast—the "mild-mannered" man versus the "ghoul of Plainfield"—is exactly what makes him so enduringly creepy.

The forensic evidence gathered from his home also pushed the field of criminal profiling forward. Robert Ressler and other early FBI profilers looked back at Gein as a foundational case for understanding "disorganized" offenders. They saw how his environment, his isolation, and his overbearing mother created a perfect storm of psychosis.

What We Get Wrong About Gein

- He wasn't a cannibal. Despite rumors, there was no evidence Gein ate his victims. He was a collector, not a consumer.

- The house didn't survive. After he was arrested, the house "mysteriously" burned to the ground. Most people think the locals did it to prevent the town from becoming a macabre tourist attraction.

- He didn't have a "kill room." He did his work in the kitchen and the shed. It wasn't a high-tech operation; it was a cluttered, rural mess.

Navigating the Legacy of Plainfield

If you're looking into the Gein case today, you have to sift through a lot of sensationalism. Many "true crime" books exaggerate the details to sell copies. However, the official police reports and the testimony from the 1957 and 1968 hearings confirm the most grisly details, including the preservation of specific body parts.

👉 See also: When Does Joe Biden's Term End: What Actually Happened

The reality of Ed Gein’s preserved vulvas and his other "trophies" serves as a reminder of how unchecked mental illness and total social isolation can warp a human mind. Gein lived in a vacuum. Without a community to tether him to reality, he created his own—a reality where the dead were his only friends and their skin was his only comfort.

For those interested in the historical and psychological aspects of the case, the best resources are the original trial transcripts and Harold Schechter’s book Deviant. These sources avoid the "slasher" tropes and focus on the grim, lonely facts of Gein's life.

To truly understand the impact of this case, one should look at how it changed Wisconsin's legal system and the way we view the "quiet neighbor." The lesson of Ed Gein isn't just about the horror he created; it's about the silence that allowed it to happen.

If you want to explore this further, start by looking at the archival photography from the Wisconsin Historical Society. They maintain a record of the investigation that provides a sobering look at the actual site, far removed from the Hollywood glitz. Understanding the geography of Plainfield—the vast, empty spaces between farms—helps explain how a man could spend a decade digging up graves without anyone noticing. Take a look at the psychological evaluations from Mendota if you can find them; they offer a window into a mind that truly didn't understand why the rest of the world was so horrified.