You’ve seen them in textbooks. Maybe you saw them in a museum exhibit or a quick Google search that felt a bit too heavy for a Tuesday afternoon. Most people think they know what pictures of the atlantic slave trade look like, but there is a massive gap between what we see and what actually happened. It’s uncomfortable. It’s messy. Honestly, looking at these images is one of the few ways to actually wrap your head around the scale of a system that treated human beings like line items in a ledger.

The first thing you have to realize is that "pictures" is a tricky word here. Cameras weren't around for most of this. We are talking about 400 years of history. Photography didn’t even show up until the 1830s, and by then, the British had already "officially" banned the trade, though it definitely didn’t stop overnight. So, when we talk about images from this era, we’re looking at a mix of hand-drawn sketches by ship surgeons, propaganda posters from abolitionists, and those haunting, late-era daguerreotypes of survivors.

It wasn't just art. It was evidence.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Visual Record

There’s this common misconception that the people drawing these images were trying to be objective. They weren't. Not even close. If you look at the famous 1788 diagram of the Brooks slave ship—you know the one, with the bodies packed like sardines in a tin—that wasn’t drawn by a slave trader to show off his efficiency. It was created by the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the African Slave Trade. They wanted to shock people. They wanted to make the average person in London or Philadelphia feel sick to their stomach. It worked.

But here’s the kicker: because these were often created by abolitionists, they sometimes simplified the reality. They wanted to show "the victim." What they often missed, or chose not to draw, was the resistance. You rarely see pictures of the atlantic slave trade that capture the shipboard revolts, the poisonings, or the sheer defiance that happened every single day on the water. We see the shackled; we rarely see the fighters.

The Architecture of the Middle Passage

When you start digging into the archives, like the ones held at the National Museum of African American History and Culture or the digital collections at SlaveVoyages.org, the technical drawings are what really get you.

💡 You might also like: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

These weren't just messy boats. They were "floating dungeons." Architects literally sat down and drafted blueprints to maximize "cargo" space. Think about that for a second. Someone used a ruler and a compass to figure out how to fit 450 people into a space meant for 200.

- The Deck Plans: These show the "spooning" position. Men were chained in pairs, right leg to left leg, usually with less than 18 inches of headroom. You couldn't even sit up.

- The Ironmongery: Sketches of the "speculum oris" are particularly haunting. It was a scissor-shaped device used to pry open the mouths of those who went on hunger strikes.

- The Branding: We have drawings and actual artifacts of the irons used to mark human skin with the initials of the Dutch West India Company or the Royal African Company.

It was industrial. That’s the word that keeps coming up. It wasn't just cruelty; it was a highly organized, bureaucratic, and profitable industry.

The Shift to Photography: 1840 and Beyond

As photography emerged, the visual record changed. We stopped seeing sketches and started seeing faces. This is where it gets incredibly heavy. One of the most famous pictures of the atlantic slave trade era is the 1863 photo of "Whipped Peter" (Gordon). His back is a literal map of scars.

While that photo was taken in the U.S. during the Civil War, it represents the tail end of the Atlantic system's legacy. But there are even rarer photos. There are images from the 1860s showing "liberated Africans" on the decks of British Royal Navy cruisers like the HMS Daphne. These photos are jarring because the people in them look... dazed. They are caught in this weird limbo between a life stolen and a future that was completely uncertain.

The camera didn't lie, but it was often used by colonial powers to say, "Look, we are the ones saving them now." It's a complicated layer of "saviors" documenting their own "benevolence" while ignoring the centuries of profit their countries had already raked in.

📖 Related: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

Why We Still Need to Look

It’s easy to say we should look away. Some people think it’s "trauma porn" or just too depressing. But historians like Dr. Marcus Rediker, who wrote The Slave Ship, argue that these visuals are necessary to counteract the sanitized version of history we often get in school.

If you don't see the shackles, you can pretend it was just a "tough migration." If you don't see the diagrams of the Brooks, you can convince yourself that the traders cared about the "health" of their "investment."

The truth is found in the margins of these pictures. Look at the corners. Look at the sailors in the background. Often, you’ll see the sheer mundane nature of it all—men eating lunch or smoking pipes while feet away, human beings are dying of dysentery and grief. That contrast is where the real horror lives. It was just another day at the office for the crew.

The Global Scale You See in the Maps

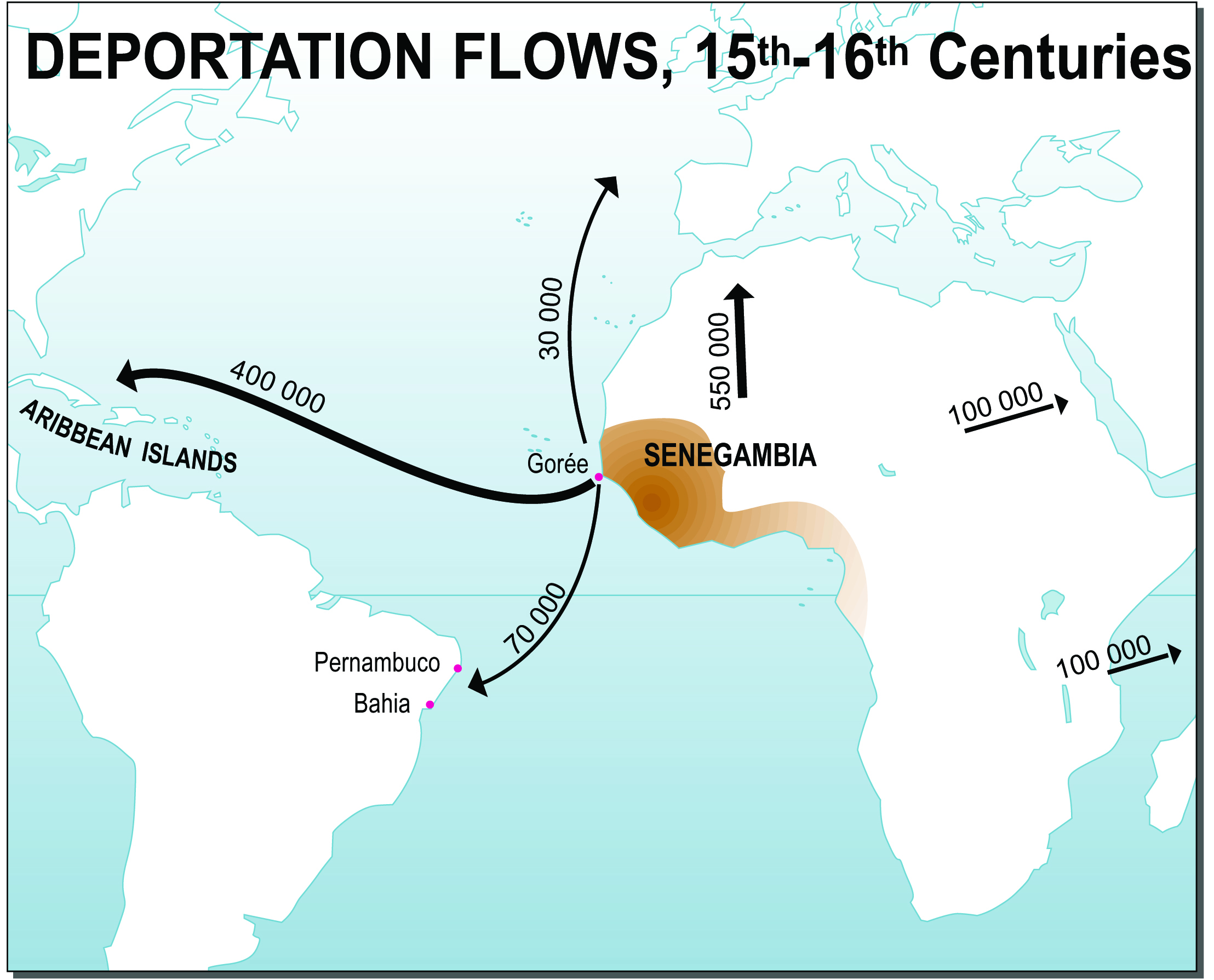

If you move away from portraits and look at the cartography—the maps of the trade—the scale is mind-bending. Most people think the majority of ships went to North America. The maps tell a different story.

Basically, the vast majority of those 12.5 million people were sent to Brazil and the Caribbean. North America was a relatively small percentage. When you look at the maps showing the "Triangular Trade," you see how sugar, tobacco, and cotton in the Americas were inextricably linked to manufactured goods in Europe and human beings in West Africa.

👉 See also: When is the Next Hurricane Coming 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

It was a global machine.

How to Engage with These Images Ethically

If you’re researching this or teaching it, you can’t just throw these images up on a screen without context. It’s too much.

First off, check the source. Is this an 18th-century engraving or a 20th-century "re-imagining"? There’s a lot of "historical" art out there that was actually painted in the 1900s and is full of inaccuracies. Stick to primary sources. The British Library and the Library of Congress have massive digital archives that are free to access.

Secondly, look for agency. Don't just focus on the suffering. Look for the images of the Maroons in Jamaica or the revolutionary leaders in Haiti. The Atlantic slave trade wasn't just a story of people being moved; it was a story of people fighting back against being moved.

Lastly, acknowledge the silence. For every one picture we have, there are a million moments that were never captured. There are no photos of the millions who died in the Middle Passage and were thrown overboard. The Atlantic Ocean is a graveyard that doesn't have a gallery.

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

Don't just stop at a Google Image search. If you want to actually understand the visual history of this era, here is what you do:

- Visit Digital Archives Directly: Skip the general search engines. Go to SlaveVoyages.org. They have a "Gallery" section that is peer-reviewed and incredibly detailed. It’s the gold standard for this data.

- Read the Narratives: Images are better when paired with words. Read The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. He describes the scenes that the artists were trying to draw. It gives the pictures a voice.

- Trace the Money: Look at the "pictures" of the wealth generated. Look at the architecture of the "Great Houses" in England and the plantations in Louisiana. Those buildings are just as much "pictures of the slave trade" as a drawing of a ship is. They are the physical manifestation of the profit.

- Support Modern Preservation: Many of the physical sites where these "pictures" took place—like the slave castles in Ghana (Elmina and Cape Coast)—are under threat from coastal erosion. Understanding the history means supporting the preservation of the real places.

The images are hard to look at, but they are a primary witness. They don't let us forget. In a world where history is often softened for comfort, these visuals stand as a blunt, unyielding reminder of what actually happened on those ships. They aren't just art; they are a reckoning.