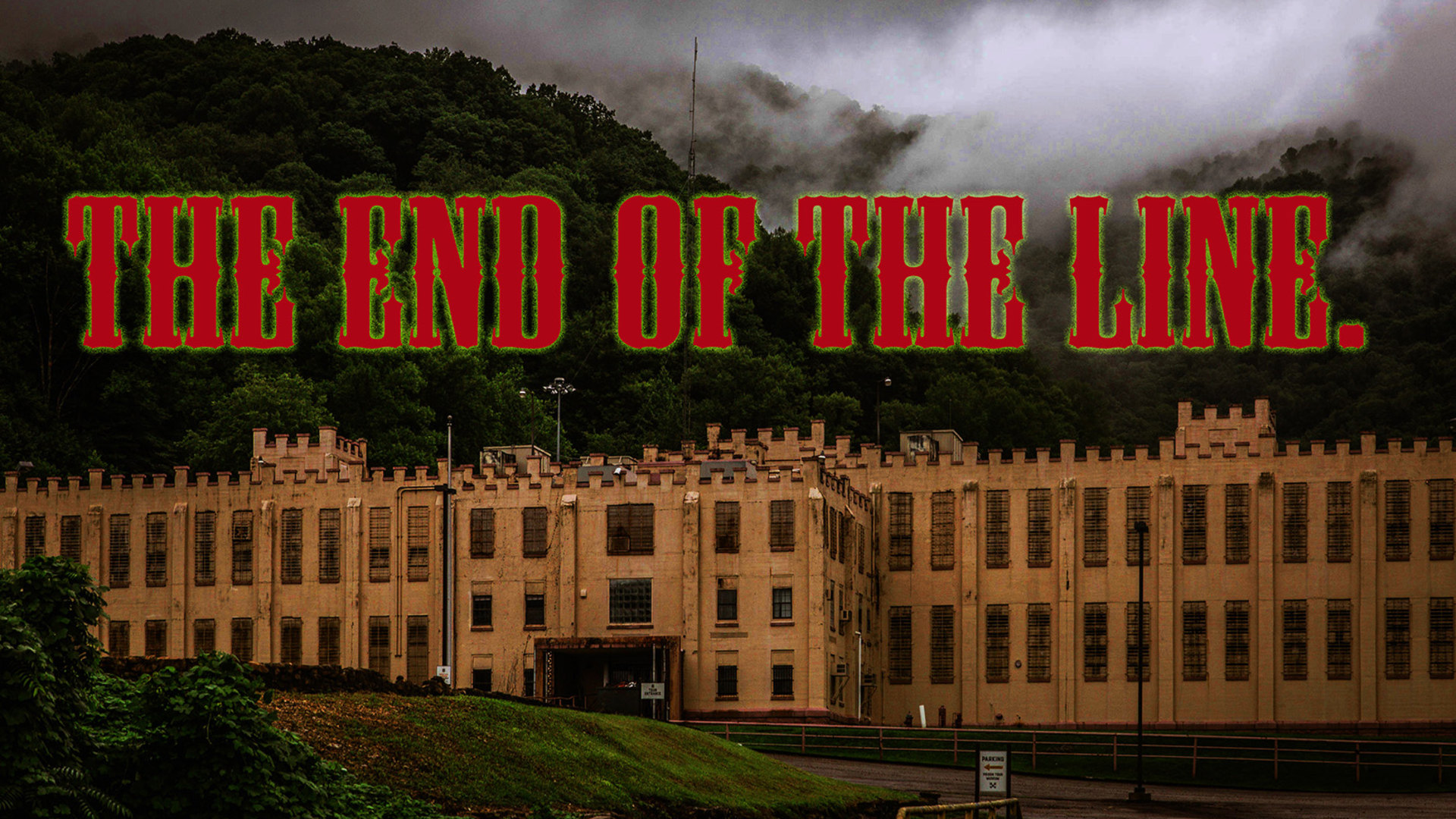

It is quiet. Really quiet. If you stand on the slope overlooking the brushy mountain state penitentiary cemetery, the first thing you notice isn't the history or the ghost stories people love to whisper about. It’s the silence of the Cumberland Mountains. Most people come to Petros, Tennessee, to see the "End of the Line"—that imposing, castle-like stone fortress that housed James Earl Ray and some of the most violent men in American history. They walk through the cell blocks, touch the cold steel, and buy a t-shirt in the gift shop. But if you keep driving past the main gates, up a narrow, winding road that feels like it’s being swallowed by the forest, you find something much more sobering.

It’s a field of forgotten names.

Actually, many of them never had names to begin with. Just numbers. The Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary cemetery is a stark, physical record of a time when the justice system was less about "corrections" and more about back-breaking labor and a permanent erasure from society. This isn't a manicured memorial. It’s a graveyard of convenience.

The Reality of the "End of the Line"

The prison opened in 1896, and honestly, it was born out of conflict. The state of Tennessee was embroiled in the Coal Creek War, a series of uprisings by free miners who were sick of the convict-leasing system. The state built Brushy Mountain to house prisoners who would work the nearby coal mines. It was a brutal existence. If a man died in the mines or succumbed to tuberculosis in the damp, cramped cells, and if his family couldn't or wouldn't pay to bring the body home, he ended up on the hillside.

You’ve got to understand the geography to understand the isolation. Brushy Mountain is surrounded by steep ridges on three sides. It’s a natural bowl. Escape was nearly impossible because the mountains themselves were the walls. That same isolation applied to the dead.

The brushy mountain state penitentiary cemetery isn't just one site. There are actually two primary burial areas. The older one is almost entirely reclaimed by the woods now. You can walk right past a grave and think it’s just a lichen-covered rock. Because, well, that’s exactly what it is. In the early days, the prison didn't spring for engraved granite. They used fieldstones. Maybe a number was scratched into it. Maybe not. Over a century of Tennessee rain and shifting soil has softened those edges until they look like any other mountain stone.

Numbers Instead of Names

Walking through the newer section of the cemetery—which is still decades old—you see the small, white concrete markers. They look like teeth pushing up through the sod.

📖 Related: Ilum Experience Home: What Most People Get Wrong About Staying in Palermo Hollywood

No birth dates.

No epitaphs about being a "beloved son."

Just a prisoner ID number.

This is where the weight of the place hits you. In the eyes of the state at the time, these men were assets that had depreciated to zero. When they died, they were processed. There are roughly 100 to 200 burials depending on which historical survey you trust, but the records from the early 20th century are, frankly, a mess. Fires, poor record-keeping, and the general chaos of the convict-leasing era mean we may never truly know everyone buried there.

The "New" cemetery (locally known as the Joe Davis Cemetery area) is where most visitors stop. It’s haunting because of the uniformity. It reflects the prison’s philosophy: once you entered those gates, your identity was stripped. Even in death, you didn't get it back.

Why the families didn't come

People often ask why families didn't claim the bodies. You have to remember the context of the early 1900s. Poverty in Appalachia and the deep South was crushing. If a man was sent to Brushy from 300 miles away, the cost of transporting a pine box via rail was often more than a year’s wages for a sharecropping family.

Shame played a part, too.

In some cases, the family simply didn't know. Communication was spotty. A letter might get lost. Or perhaps the prisoner had severed all ties years before. So, they stayed in the dirt of Morgan County.

👉 See also: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

The Haunting and the History

Let’s talk about the ghost stories, because if you search for the brushy mountain state penitentiary cemetery, you're going to find "paranormal investigators" claiming it’s the most haunted spot in the South.

Is it?

Locals in Petros have stories that go back generations. They talk about "The Man in the Woods" or weird lights on the ridges. But the real horror isn't a jump-scare. It’s the factual history of the place. We’re talking about men who worked in 48-inch coal seams, crawling on their bellies for 12 hours a day, only to die of exhaustion or a rock fall.

When you stand in the cemetery, the atmosphere is heavy. It's not necessarily "evil," but it is heavy. It’s the accumulation of a thousand unsaid goodbyes. The prison itself, which is now a tourist attraction with a distillery and a restaurant, can feel a bit like a theme park during the day. But the cemetery? The cemetery remains untouched by the commercialization. It’s still raw.

How to Visit Respectfully

If you’re planning a trip to the Historic Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary, you shouldn't skip the cemetery, but you need to be prepared.

- The Drive: The road is steep. If there’s been heavy rain or snow, be careful. It’s a one-lane-ish vibe in places.

- The Terrain: It’s not flat. Wear actual shoes, not flip-flops. The ground is uneven, and the brush can be thick.

- The Ethics: Don't be that person. Don't do "grave rubbing" on the markers. Don't leave trash. Don't try to dig. It sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised.

The cemetery is technically on state-owned land or managed by the historic site, so check in at the main gate before you head up. Sometimes they have specific hours or restrictions based on maintenance.

✨ Don't miss: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

The Legacy of the Stones

What can we learn from a patch of dirt filled with numbered stones?

The brushy mountain state penitentiary cemetery is a mirror. It shows us what happens when a society decides that some people are disposable. In the 1970s and 80s, the prison moved toward a more modern "correctional" model, and the burials on the hill stopped as better systems for handling indigent remains were put in place.

But those markers remain.

They are a permanent part of the Tennessee landscape now. They’ve survived the closing of the mines. They’ve survived the closing of the prison in 2009. They’ll likely be there long after the prison museum’s paint starts to peel.

For those interested in genealogy, there have been recent efforts by local historians to map these numbers back to the original intake ledgers. It’s slow, painstaking work. Sometimes the ledger says "John Doe." Sometimes it just says "Colored Male, age 24." But every now and then, a researcher connects a number to a name, and a family tree finally gets a closing date for a long-lost uncle or grandfather.

Practical Steps for Your Visit

- Book the Warden’s Tour: If you want the real dirt, the tours led by former inmates or guards provide the best context, though they focus more on the prison than the graveyard.

- Check the Weather: Petros is in the mountains. If it's raining in Knoxville, it's pouring at Brushy. The fog in the cemetery can be so thick you can't see your own feet—which, honestly, adds to the vibe, but makes walking dangerous.

- Research the Ledgers: Before you go, look at the Tennessee State Library and Archives. They have digitized some of the early Brushy Mountain inmate records. Having a few names in your head makes the numbered stones feel much more human.

The brushy mountain state penitentiary cemetery isn't just a side-trip. It's the final sentence of the prison's story. It’s a place that demands a moment of silence. You don't have to be religious or superstitious to feel the weight of those Cumberland stones. You just have to be human.

When you leave, drive slowly back down into Petros. Look at the mountains. They’re beautiful, but for the men under those numbered markers, they were the last thing they ever saw—and the only walls they couldn't climb.

To truly grasp the scale of the history here, start your research by cross-referencing the Tennessee Department of Correction's historical inmate indices with the Morgan County burial records. This will give you a list of names that were never carved into the concrete, allowing you to pay respects to the individuals behind the numbers during your visit. Pack a pair of rugged boots, a physical map of the Petros area (cell service is notoriously spotty in the "bowl"), and allow yourself at least two hours of daylight to explore the grounds without rushing.