You see a brown spider in your bathtub. Your heart does a little skip. Immediately, your brain screams "brown recluse!" and you’re suddenly considering burning the whole house down. But here is the thing: unless you live in a very specific slice of the United States, that spider is almost certainly something else. People are terrified of these things. It’s a bit of a national obsession, honestly. But if you actually look at a verified brown recluse range map, you’ll realize that the vast majority of "recluse sightings" in places like California, Florida, or Maine are just cases of mistaken identity.

The fear is real, but the geography is often wrong.

Expert arachnologists like Rick Vetter from the University of California, Riverside, have spent decades trying to calm people down about this. He’s basically the leading authority on why everyone thinks they’ve found a recluse when they haven’t. Vetter once ran a study where he asked people to send him spiders they thought were recluses. Out of nearly 1,800 spiders sent from across the country, hundreds of them—from areas outside the spider's native range—were actually just harmless cellar spiders, wolf spiders, or even common house spiders. Only a tiny fraction were actually Loxosceles reclusa.

Where the Brown Recluse Actually Lives

Geography matters. If you aren't in the "fiddle-back" zone, you can probably breathe a sigh of relief.

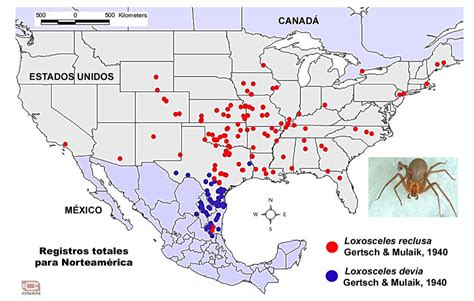

The brown recluse range map is surprisingly fixed. We aren't seeing some massive migration due to climate change or hitchhiking in boxes, at least not in numbers that create new populations. The core territory is shaped like a giant, slightly lopsided blob in the central and southeastern U.S. Think Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, and parts of Tennessee and Kentucky. It also reaches into southern Illinois, Indiana, and a sliver of Georgia and Ohio.

If you’re in Seattle? No.

Miami? Nope.

Los Angeles? Definitely not.

There are "cousins," sure. In the Southwest, you might find the desert recluse (Loxosceles deserta). It looks similar, behaves similarly, but it stays in the desert. It isn't the infamous brown recluse that makes the news. The actual Loxosceles reclusa is a homebody. They don't want to travel. They like their specific humidity and temperature.

Reading the Map Like a Pro

When you look at a brown recluse range map, you'll notice the borders are pretty sharp. They don't just "kind of" live in South Carolina; they are mostly absent from the Atlantic coast. It’s a midcontinental species.

Why does this matter? Because of the "diagnosis by distance" rule.

Doctors in areas where the spider doesn't exist often diagnose "spider bites" based on a nasty-looking skin lesion. But here is a wild fact: MRSA (a staph infection) looks almost exactly like a recluse bite. In places like Colorado or New York, where recluses don't live, medical professionals still tell patients they were bitten by one. It’s a bit of a medical myth that won't die. If you see a map that shows recluses all over the West Coast, that map is lying to you.

📖 Related: Birth Chart Analysis Vedic Astrology: Why Your Western Sign Is Probably Wrong

The "Hitchhiker" Myth

You've probably heard that they travel in bananas or shipping boxes. While a single spider can end up in a box and travel to Vermont, it doesn't mean Vermont now has a brown recluse problem. One spider does not an infestation make. They need a mate, the right climate, and a lack of competition. Most of the time, a "hitchhiking" recluse dies before it ever finds a partner.

Identifying the Real Deal (It’s Not Just the Violin)

Everyone tells you to look for the violin shape on the head. "Fiddle-back spiders," they call them. But honestly? That is terrible advice for a novice. Plenty of spiders have dark marks on their cephalothorax.

If you want to be a nerd about it, you have to look at the eyes. Most spiders have eight eyes in two rows. The brown recluse is a weirdo—it only has six eyes. They are arranged in three pairs (dyads). There’s one pair in the front and one pair on each side. It’s very distinct if you have a magnifying glass or a high-res camera.

Also, look at the legs.

- No spines.

- Uniform color (no stripes, no spots).

- Fine hairs that give them a velvety look.

If the spider has big "spikes" on its legs or striped "socks," it is 100% not a brown recluse. It’s probably a wolf spider or a grass spider. Those guys are the good guys; they eat the bugs you actually hate.

🔗 Read more: Why CeraVe Moisturizing Cream with Hyaluronic Acid is Still a Skincare Essential

Living in the Red Zone

What if the brown recluse range map shows you’re right in the thick of it? What if you live in St. Louis or Little Rock?

First off, don't panic. People in these areas live with recluses for decades and never get bitten. There’s a famous case of a family in Kansas who collected over 2,000 brown recluses in their home over six months. They lived there for years. Total number of bites? Zero.

They are called "recluse" for a reason. They aren't aggressive. They don't hunt humans. They want to sit in a dark, dry corner behind your water heater and eat dead crickets. Most bites happen when someone puts on a shoe that’s been in the closet for six months or grabs a box in the attic without looking. The spider gets squished against skin, panics, and bites defensively.

How to Recluse-Proof Your Life

If you are within the range, you just need to change your habits slightly.

- Stop using bed skirts. They provide a literal ladder for spiders to climb from the floor to your sheets.

- Move the bed. Keep it a few inches away from the wall.

- Shake everything. Before you put on boots, gloves, or a jacket that’s been sitting out, give it a vigorous shake.

- Plastic bins are your friend. Cardboard boxes are like luxury hotels for recluses. They love the ripples in the cardboard. Switch to sealed plastic bins for storage.

The Bite: Fact vs. Fiction

We’ve all seen the "necrosis" photos on the internet. They are terrifying. But here is the nuance: about 90% of brown recluse bites heal just fine without any major medical intervention. They might just look like a red mark or a small blister.

Only a small percentage (around 10%) result in significant tissue damage or "loxoscelism." This is where the venom causes the skin to die. Even then, it’s rarely fatal. Usually, it's just a slow-healing wound. The real danger is if you have a systemic reaction—fever, chills, rash—which is much rarer but definitely requires a trip to the ER.

If you think you've been bitten, and you're in the area shown on the brown recluse range map, try to catch the spider. Even a smashed spider can be identified by an expert. It helps the doctors rule out other things like Lyme disease, fungal infections, or bacterial issues that look like bites.

Why the Map Changes (Or Doesn't)

You might see articles claiming recluses are moving north. Is it true? Not really. While some species shift ranges as the world warms, the brown recluse is remarkably stubborn. They are poor dispersers. They don't "balloon" like other spiders (where babies fly on strands of silk). They have to walk or be carried by humans.

Because they are so dependent on human structures in the northern parts of their range, they stay isolated. You might find a colony in a specific warehouse in Ohio, but they won't necessarily spread to the woods or the houses next door. The "range" is more about where they can survive and thrive outdoors and in unheated buildings.

Actionable Steps for Homeowners

If you’re staring at a brown recluse range map and realize you're in the "danger zone," don't go buying every bug spray at the hardware store. General pesticides often don't work well on recluses because they have long legs that keep their bodies off the ground, so they don't pick up the poison.

Instead, focus on these moves:

👉 See also: 20 C to Fahrenheit: Why This Specific Temperature is the Secret to Comfort

- Deploy Sticky Traps: Put them along baseboards and behind furniture. This is the single most effective way to reduce the population. It also helps you monitor how many you actually have.

- Seal the Gaps: Use caulk to close up spaces around plumbing, electrical outlets, and baseboards.

- Clear the Perimeter: Move woodpiles, heavy brush, and debris away from the foundation of your house.

- Verify the Species: Before you spend $500 on an exterminator, take a photo and send it to your local university extension office or use a reputable ID group online. Most of the time, your "recluse" is just a harmless neighbor.

Understanding the map is about reclaiming your peace of mind. If you are in New England or the Pacific Northwest, you can stop worrying about this particular spider. If you are in the Midwest or South, a little bit of caution and some plastic storage bins are all you really need to coexist safely.

Immediate Next Steps

- Check your location: Compare your town to the official USGS or Rick Vetter range maps. If you are outside the shaded area, any brown spider you see is almost certainly a nursery web spider, wolf spider, or house spider.

- Set out traps: If you are in the range, place 3-5 sticky monitors in dark corners. Check them in a week to see what's actually crawling around.

- Inspect storage: Move any cardboard boxes away from walls and consider swapping them for plastic containers to eliminate the spiders' favorite hiding spots.