You’ve probably seen the old movies. A tall, impeccably dressed Black man in a crisp white jacket handles heavy luggage with a polite smile, making up berths on a rocking train in the middle of the night. That was the "Pullman Porter." It looks glamorous on film, but the reality was a grueling, often exploitative grind that eventually birthed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first Black-led labor union to actually force a major American corporation to the bargaining table. Honestly, it's a miracle it happened at all.

George Pullman was a genius at marketing but a nightmare of a boss. He specifically hired formerly enslaved men to staff his luxury "palace cars" because he knew they’d be desperate for work and culturally conditioned—at the time—to be subservient. He even forced them all to answer to the name "George," regardless of their real names. Imagine that. You spend 400 hours a month on a train, and you don’t even get to keep your own identity.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters didn't just fight for more cents per hour. They fought for the right to be called by their own names. They fought for the right to sleep more than three hours a night in a cramped "top berth" while the passengers slept in luxury. It was a battle for basic human dignity that lasted over a decade.

The Man Who Couldn't Be Bought: A. Philip Randolph

Most people think of the 1960s when they hear about the Civil Rights Movement. But the seeds were sown in 1925 in a Harlem basement. That’s where A. Philip Randolph, a soft-spoken but iron-willed editor, took the lead of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

He wasn't a porter himself. That was a strategic move.

The Pullman Company had a nasty habit of firing any porter caught talking about a union. Since Randolph didn't work for Pullman, they couldn't fire him. They tried to bribe him instead. They sent him a blank check. Seriously. They told him he could write any number he wanted on it if he’d just walk away. Randolph sent it back.

📖 Related: Kimberly Clark Stock Dividend: What Most People Get Wrong

The union’s struggle was basically a David vs. Goliath story, but David had to wait twelve years to get his slingshot ready. Between 1925 and 1937, the porters faced "company unions"—fake organizations set up by the bosses to trick workers—and brutal intimidation. If a porter was seen carrying a pro-union newspaper like The Messenger, he was out. Gone. No pension, no paycheck, no recourse.

1937: The Year the World Changed for Black Labor

It took twelve years of organizing, but the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters finally won. On August 25, 1937, the Pullman Company signed a contract.

It was massive.

We’re talking about $2 million in total pay increases. The work month was cut from 400 hours to 240. Porters finally got paid for the "preparatory time" they spent setting up the cars before the train even left the station—work they had previously done for free.

But the impact went way beyond the paycheck. This victory proved that Black workers could organize and win against the most powerful industrial titan in the country. It turned the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters into a blueprint for the later Civil Rights Movement. In fact, many of the people who organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott, like E.D. Nixon, were actually Pullman Porters. They were the "traveling ambassadors" of the movement, secretly carrying Black newspapers and civil rights literature from the North to the South on their routes.

👉 See also: Online Associate's Degree in Business: What Most People Get Wrong

The Gritty Details of the Job

To understand why they fought so hard, you have to look at the math. A porter in the 1920s might make $60 a month. That sounds okay for the time until you realize they had to pay for their own uniforms, their own meals, and even the polish they used on the passengers' shoes.

They were essentially independent contractors who were treated like servants.

- They had to stay awake 20 hours a day.

- They were only allowed to sleep in the smoking car if it was empty.

- They had to pay for any missing towels or equipment out of their own pockets.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters ended these "occupational expenses." It made the job a respectable, middle-class career that allowed thousands of Black families to send their kids to college.

Why We Still Talk About Them in 2026

The legacy of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters isn't just a history lesson. It’s the origin story of the modern Black middle class.

If you look at the lineage of many successful African American families today, you’ll find a Pullman Porter in the family tree. They were the ones who saw the whole country, met people from all walks of life, and realized that the status quo wasn't the only option. They used their union wages to buy homes and build communities.

✨ Don't miss: Wegmans Meat Seafood Theft: Why Ribeyes and Lobster Are Disappearing

And let's be real: the tactics they used are still relevant. When you see modern gig workers or service employees organizing today, they’re using the same playbook Randolph and Milton Webster developed. They focused on community support, international pressure, and relentless persistence.

Common Misconceptions

A lot of people think the union was just about "Black rights." It was actually a pivotal moment for all labor. Before the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters succeeded, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) was pretty hesitant to support non-white workers. Randolph’s persistence forced the broader labor movement to realize that you can’t have a strong working class if you exclude a huge chunk of the workforce based on race.

Another myth? That the porters were "lucky" to have the jobs. While it was a "good" job compared to sharecropping, it was still a system built on a foundation of racial hierarchy. The union didn't just want the job to be better; they wanted the system to be different.

Practical Lessons from the Porters' Victory

If you're looking at the history of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and wondering what it means for you, consider these takeaways. Change doesn't happen overnight—it took them twelve years to get that first contract. Twelve years of being fired, blacklisted, and broke.

- Strategic Leadership Matters: Choosing a leader who couldn't be fired by the company (Randolph) was a masterstroke.

- Economic Power is Political Power: The union used their wages to fund the early stages of the Civil Rights Movement.

- Identity is Non-Negotiable: Fighting for the right to use their own names was just as important as the $2 million raise.

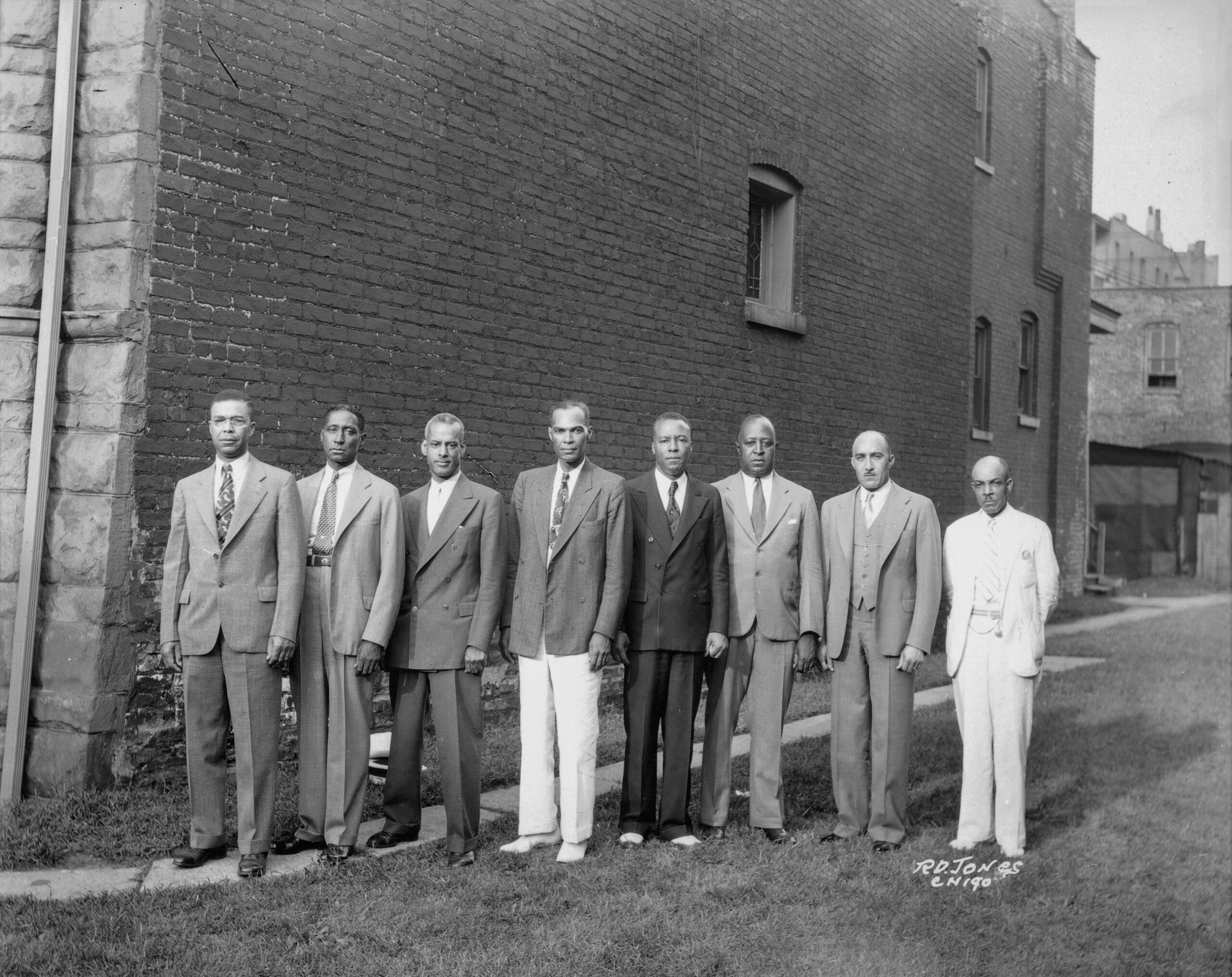

To truly honor this history, it's worth visiting sites like the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum in Chicago. It’s a small place, but it holds the weight of a massive legacy. You can also look into the records of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center, which houses many of the original documents from the union’s early days.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters reminds us that the "American Dream" wasn't just handed out. It was negotiated, protested for, and won in the quiet hours of a swaying train car.

Next Steps for Deeper Research

- Search the National Archives: Look for the records of the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC), which Randolph helped create.

- Read "A. Philip Randolph, Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement" by Paula F. Pfeffer: It gives a nuanced look at how the union’s success led directly to the 1963 March on Washington.

- Support Labor Museums: Many regional museums in railroad hubs like Chicago, Oakland, and St. Louis have specific exhibits on the porter experience that go far beyond the textbooks.

The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters is a testament to the idea that collective action is the only real way to move the needle on justice. It's about more than trains; it's about the dignity of work.