It starts with a scream. Honestly, if you’ve ever stood in the athlete’s village in Hopkinton on a Monday morning in April, you know that sound. It’s a mix of nervous energy, the smell of Tiger Balm, and the realization that you’re about to run through eight different towns just to get to a finish line in a city you can't even see yet. Everyone looks at the Boston Marathon course map and thinks they have it figured out. You see a line that mostly goes down. You think, "Hey, gravity is my friend."

But the map is a liar. Or, at the very least, it's a massive oversimplification of a 26.2-mile psychological war.

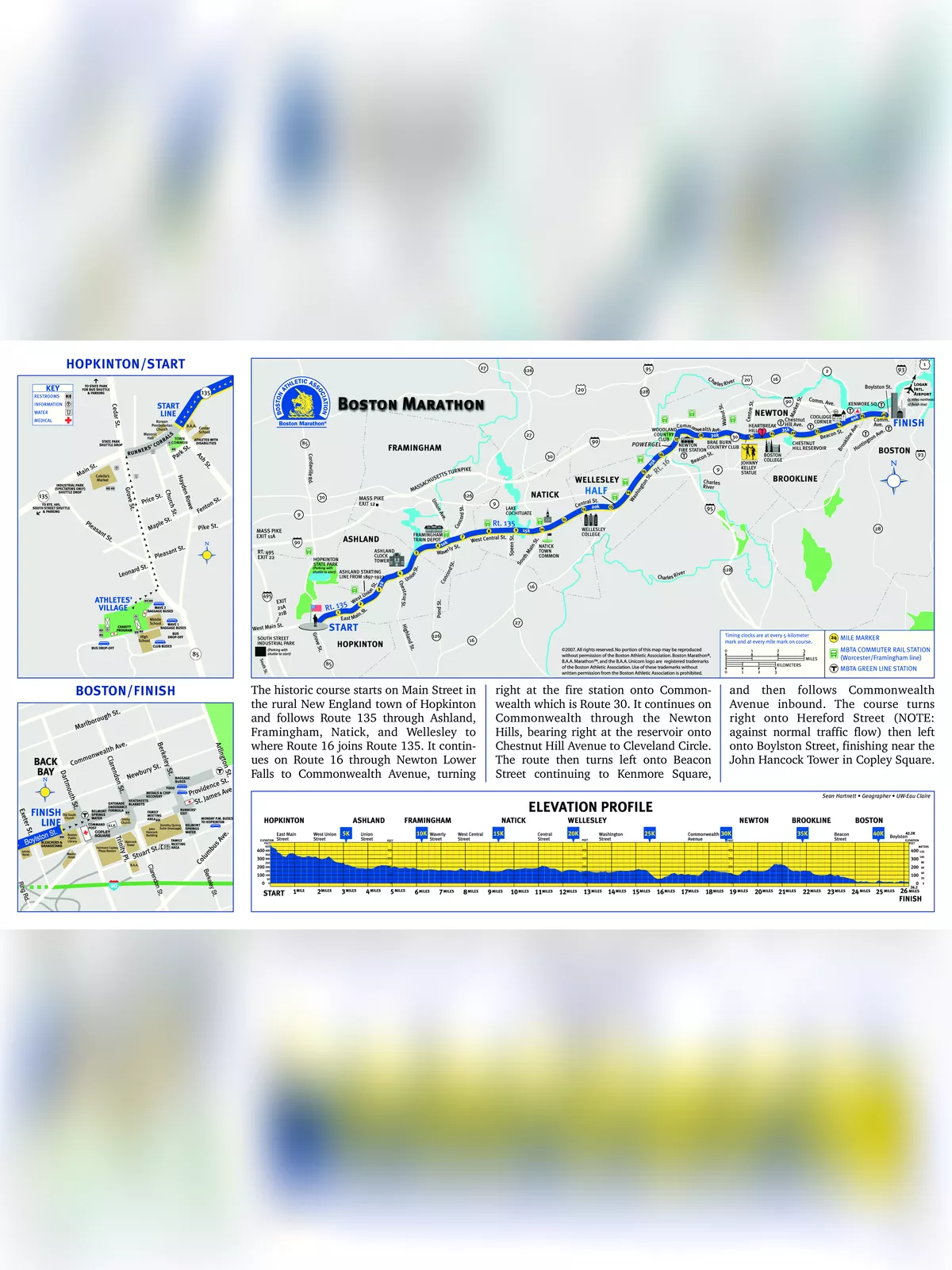

The Boston Marathon isn't a loop. It’s a point-to-point trek from the rural, quiet outskirts of Hopkinton to the skyscraper-shadowed pavement of Copley Square. Because it’s a net downhill, it doesn’t technically qualify for world records, but ask any elite runner if they’d rather run a flat Berlin loop or the jagged teeth of the Newton Hills. They’ll choose Berlin every time. Boston is about survival.

The Deceptive Start: Hopkinton and Ashland

The first few miles of the Boston Marathon course map are basically a trap. You leave the start line on Main Street and immediately plummet. It’s a steep drop. Your legs feel amazing because you’ve spent months tapering and you’re riding a wave of adrenaline. You want to fly. Don't.

If you blow your quads in the first four miles of Ashland, you’re done. You just don't know it yet. The road is narrow here. It feels intimate, almost like a local 5k, passing by colonial-style homes and small-town gas stations. You’ll hit the 5k mark and realize your pace is twenty seconds faster than your goal. That’s not because you’re a superhero; it’s because the geography is doing the work for you. Veteran coaches like Jack Fultz, who won the "Run for the Hoses" in 1976, always warn about this specific section. You have to hold back. You have to fight the urge to race.

Framingham and Natick: The Long Middle

By the time you hit Framingham (Mile 6), the crowd starts to thicken. The course flattens out a bit, but it’s never truly flat. It’s "rolling." That’s the word runners use to describe terrain that slowly saps your energy without you noticing.

Natick is where the race settles into a rhythm. You pass through the town green around Mile 10. The energy is high, but the scenery is repetitive. If you look at the Boston Marathon course map, this is the straightest, most predictable part of the journey. It’s also where the mental fatigue kicks in. You’ve been running for nearly an hour, and you aren’t even halfway. This is where you see the "Wall of Sound" approaching—the Wellesley Scream Tunnel.

📖 Related: How to watch vikings game online free without the usual headache

The Scream Tunnel and the Halfway Point

You hear Wellesley College before you see it. Literally.

The students there have a tradition of lining the right side of the road around Mile 12.5. It is a literal wall of noise. It’s iconic. It’s legendary. It’s also incredibly distracting. You’ll find yourself speeding up just because the energy is so infectious. But right after that, you hit the 13.1-mile mark. You’re halfway to Boston. This is the moment of truth. If your breathing is heavy here, the next thirteen miles are going to be a nightmare.

The Newton Hills: Where Dreams Go to Die

Most people focus on Heartbreak Hill. It’s the one everyone talks about. But on the Boston Marathon course map, the "Newton Hills" are actually a series of four distinct climbs starting after you cross the Route 128 overpass at Mile 16.

- The Fire Station Turn: You turn right onto Commonwealth Avenue. It’s a sharp turn, and suddenly, you’re looking up. This first hill is a gut punch because it comes right when your glycogen stores are hitting zero.

- The Intermediate Rises: The second and third hills aren't as famous, but they’re relentless. They break your rhythm. You go up, you get a tiny bit of downhill to tease you, and then you go back up.

- Heartbreak Hill: This is the big one. It’s about half a mile long, rising between Miles 20 and 21. It’s not the steepest hill in the world—if you ran it on a Sunday training run, you’d barely notice it. But at Mile 20? It’s a mountain.

The nickname "Heartbreak Hill" actually comes from the 1936 race. Ellison "Tarzan" Brown was leading, and defending champ Johnny Kelley caught up to him. Kelley gave Brown a friendly pat on the back as he passed. That gesture ignited something in Brown, who surged ahead and won, "breaking Kelley’s heart." It’s been a site of carnage ever since.

The Descent Into Boston

If you make it to the top of Heartbreak, you see the Citgo sign. Well, sort of. You see it in the distance. It looks like it’s a mile away. It’s actually five miles away.

The Boston Marathon course map shows a significant drop from Mile 21 to Mile 25. This is where the quad damage you did in Hopkinton comes back to haunt you. Running downhill when your legs are shredded is arguably more painful than running uphill. You’re passing through Brookline now, through Cleveland Circle and along Beacon Street. The crowds are ten deep. The noise is constant.

👉 See also: Liechtenstein National Football Team: Why Their Struggles are Different Than You Think

You pass Fenway Park. You see the Citgo sign looming larger and larger. You go under the Massachusetts Avenue overpass—a tiny, dark dip that feels like a canyon—and then you’re almost there.

Right on Hereford, Left on Boylston

This is the most famous sequence in road racing.

You take a short, sharp right onto Hereford Street. It’s a bit of a climb. Then, you take a wide left onto Boylston Street. The finish line is visible. It’s about 600 yards away. This stretch feels like it takes an eternity. The flags are flying, the grandstands are screaming, and the blue and yellow finish line is finally under your feet.

You’re in the heart of the Back Bay. You’ve just completed a course that has stayed essentially the same since 1924 (when the start was moved from Ashland to Hopkinton to comply with the official Olympic distance).

Technical Realities of the Course

Understanding the Boston Marathon course map requires looking at the elevation profile. The start is at about 490 feet above sea level. The finish is barely 10 feet above sea level.

- Net Drop: Roughly 450 feet.

- The Problem: Because it's a point-to-point course running west to east, a tailwind can lead to blistering times (like Mutai’s 2:03:02 in 2011), but a headwind coming off the Atlantic can turn the race into a slow-motion slog (like the 2018 "monsoon" year won by Des Linden).

- Camber: The roads are old. New England winters do a number on the asphalt. The "crown" of the road can be tough on your ankles and hips if you stay on one side too long.

The B.A.A. (Boston Athletic Association) doesn't change the route for fun. It’s a historical landmark in itself. Every crack in the pavement near Boston College, every dip in the road in Wellesley, it’s all part of the lore.

✨ Don't miss: Cómo entender la tabla de Copa Oro y por qué los puntos no siempre cuentan la historia completa

Actionable Strategy for Navigating the Map

If you’re planning to run or even just spectate, don't just look at a 2D image of the route.

First, study the Newton section specifically. If you're a runner, train on "rolling" hills, not just long inclines. You need to teach your legs how to transition from climbing back to descending without seizing up.

Second, for spectators, the Boston Marathon course map is a logistical puzzle. Don't try to see your runner in more than two spots unless you're an expert with the MBTA "T" system. The best move is often catching them in a quiet spot like Natick and then taking the Commuter Rail or Green Line to the final mile.

Third, acknowledge the weather. The map faces east. If the sun is out, you’re staring at it for a large chunk of the morning. If the wind is blowing from the east, you’re fighting it the whole way.

Finally, remember that the finish line isn't just a mark on the ground. It’s a high-security zone. If you’re meeting someone, pick a spot several blocks away, like the Public Garden or a specific hotel lobby. The area around the finish line on Boylston is strictly controlled and incredibly crowded.

The course is a beast. It’s unfair, it’s hilly in the wrong places, and it’s often cold and wet. But that’s why the medal means what it does. You didn't just run 26.2 miles; you conquered the road from Hopkinton to Boston.

Next Steps for Success:

- Download the official B.A.A. app to track athletes in real-time, as the "map" is much more useful when it has live data points moving across it.

- Review the hydration station locations. They are roughly every mile on both sides of the road starting at Mile 2, which is unique to Boston and helps prevent the cross-traffic chaos seen in other majors.

- Check the MBTA schedule changes for Marathon Monday. Several stations near the finish line, like Copley, are closed entirely on race day for safety and crowd control.