You’re sitting in a quiet room, surrounded by piles of books written by the smartest men in history. You pick one up, hoping for a bit of wisdom, but instead, you find page after page calling you—and every other woman—a "vessel of vice," "intellectually stunted," or basically just a mistake of nature.

That was the vibe in 1405 for The Book of the City of Ladies Christine de Pizan.

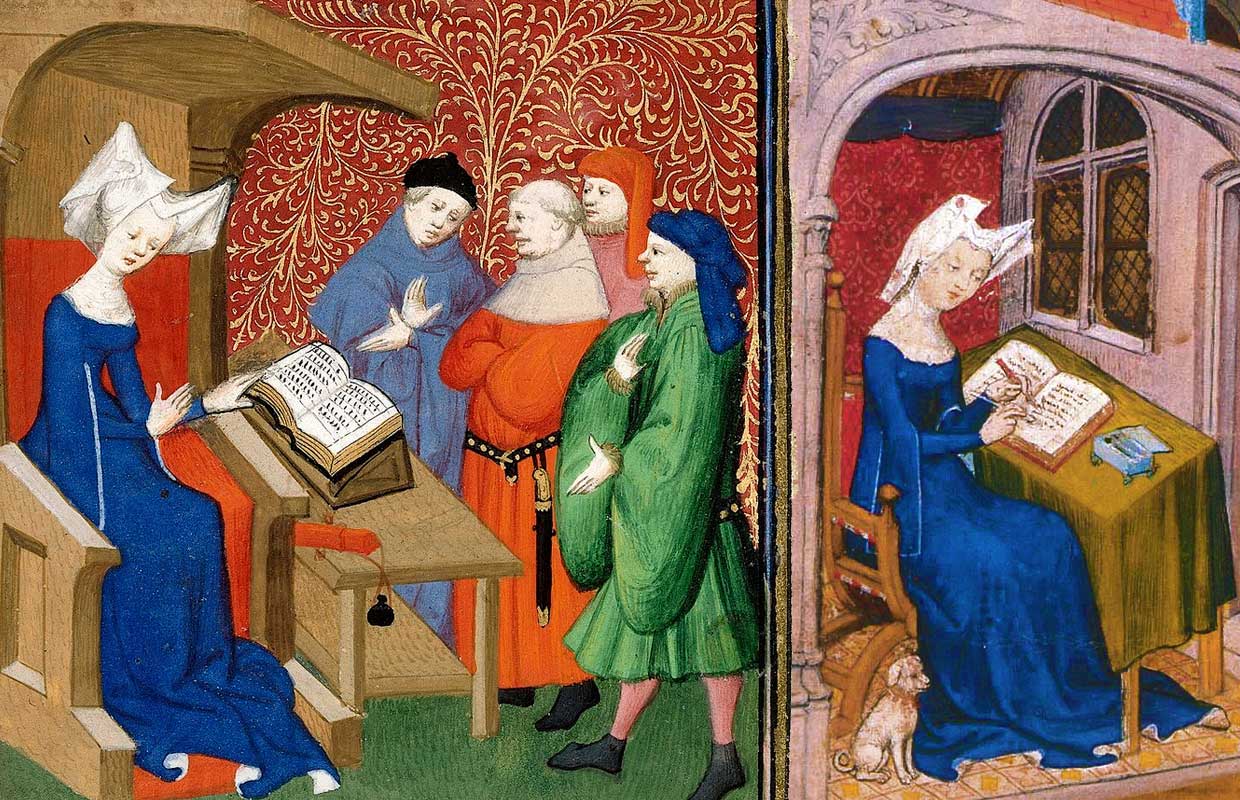

Imagine the sheer guts it took to look at the entire Western canon, roll your eyes, and decide to rewrite history from your desk in medieval Paris. Honestly, it’s kinda wild that we don’t talk about Christine more. She wasn’t just a "lady who wrote"; she was the first woman in Europe to make a professional living by her pen. After her husband, Estienne de Castel, died of the plague, she didn’t just shrivel up. She fought for her kids, her mother, and her niece by becoming a literary powerhouse.

The Day Christine de Pizan Flipped the Script

The book starts with Christine—the character—feeling absolutely miserable. She’s reading a book by a guy named Matheolus (whose Lamentations were basically a medieval Reddit rant against wives), and it gets to her. She starts wondering if maybe the guys are right. Maybe women are just inherently flawed?

Then, three "celestial ladies" show up in her room: Lady Reason, Lady Rectitude, and Lady Justice.

They don't just give her a pep talk. They tell her to pick up her trowel and start building. They aren't building a physical city with bricks, but a "City of Ladies" made of stories—real and mythological—that prove women aren't just equal to men, but often lead the way.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Building the Foundation with Lady Reason

Lady Reason doesn't play around. She helps Christine clear out the "rubbish" of misogyny. Every time a male writer says women aren't capable of learning, Reason drops a name. She brings up Sempronia, who had a memory like a steel trap and could persuade anyone of anything. She talks about the Amazons and how they built a whole society while the men were... well, not being helpful.

The coolest part? Christine isn't just reciting facts. She’s engaging in a dialogue. She’s asking the questions we’d ask: "If women are so smart, why don't they go to school?" And Reason basically says, "Because nobody lets them, girl."

Laying the Streets with Lady Rectitude

Once the walls are up, Lady Rectitude steps in to populate the city. This is where things get personal. She talks about the emotional and moral strength of women. She mentions Sappho (though, heads up, medieval Christine notably skips the part about Sappho’s sexuality to keep things "virtuous") and various queens who ruled better than the kings who preceded them.

She's basically creating a "Who's Who" of powerful women to show that virtue isn't gendered. It’s about character.

Why We Still Get Her Wrong

A lot of people today try to slap a modern "feminist" label on her and call it a day. But that’s a bit of a stretch. Christine was a product of her time. She believed in the social hierarchy. She wasn’t out there demanding the right to vote or smashing the patriarchy in the streets.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

She was doing something much more subtle and, in some ways, more radical for 1405.

She was arguing for intellectual agency.

She believed that if women were educated, they would be just as virtuous and capable as men. But she also believed that women should use that education to be better wives, mothers, and citizens within the existing system. It’s a bit of a "conservative feminism" if you want to use modern terms, but even that doesn't quite fit.

The Myth of the "Silent" Medieval Woman

People think medieval women were just sitting in towers waiting to be rescued. Christine de Pizan proves they were running households, managing estates, and, in her case, running a full-blown scriptorium. She oversaw the production of her own manuscripts. She was an entrepreneur.

She didn't just write the book; she branded it.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

The Weird Side of the City

Honestly, some parts of The Book of the City of Ladies Christine de Pizan are just plain weird by today’s standards. Christine had a thing for blonde hair. Almost every "ideal" woman in her book is described as blonde. She also had a habit of "Christianizing" everyone.

- Medusa? Just a really beautiful girl with great hair. No snakes.

- Minerva? An exceptionally smart human girl who people mistook for a goddess.

- Ceres? Just a wise woman who happened to invent agriculture.

She was stripping away the magic to show that these women were real, human examples of what a woman’s mind could achieve. She wanted to prove that greatness was in the "nature" of women, not just some divine accident.

The Actionable Legacy of Christine de Pizan

So, what do we actually do with this? Reading Christine isn't just a history lesson. It’s a blueprint for how to handle a world that tells you you’re "less than."

- Audit your inputs. Christine was depressed because she was reading trash books that hated women. Look at what you're consuming. If the content you're watching or reading makes you feel inherently flawed, throw it in the "rubbish pile" like Lady Reason did.

- Build your own "City." Who are the women (or people) in your life who inspire you? Create your own mental "City of Ladies." When you feel like you can't do something, call on their stories.

- Control your narrative. Christine didn't wait for a man to write her biography. She wrote her own story into her books. She made herself the protagonist. Don't let someone else define your history or your potential.

If you want to dive deeper, don't just read a summary. Pick up a translation by Rosalind Brown-Grant. She captures the Latinate, sophisticated flow of Christine’s prose without making it feel like a dusty textbook.

The City of Ladies is still standing. You just have to walk through the gates.

To better understand the historical context of Christine's work, you should research the "Querelle des Femmes"—the centuries-long literary debate about the nature of women that Christine essentially kicked into high gear. This will help you see how her arguments were used by later writers like Agrippa von Nettesheim or even Mary Wollstonecraft centuries later. Additionally, look for digitized versions of the original illuminated manuscripts from the British Library to see how she visually represented the construction of her allegorical city.