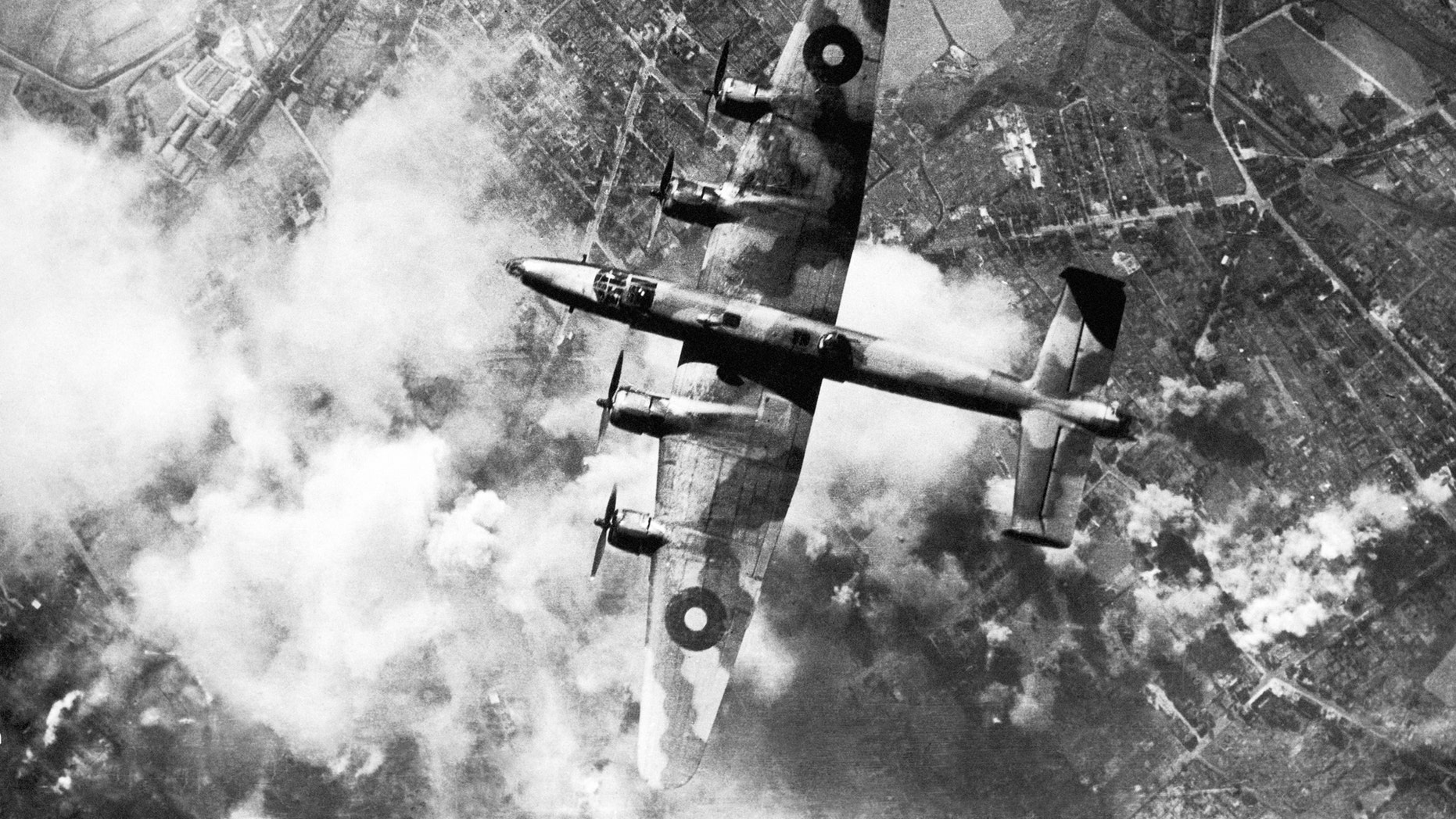

September 7, 1940, started out like a dream. It was one of those late summer days where the sun just hangs there, golden and still, over the Thames. Then the sirens started. Most Londoners didn’t run—not at first. They’d heard the "moaning Minnie" so many times during the Phoney War that it had become background noise. But this was different. Within minutes, nearly 350 German bombers and 600 fighters turned the sky over the East End into a bruised purple haze of smoke and oil. This was the start of the bombing of London WWII, an event we now call the Blitz, but back then, it just felt like the end of the world.

History books make it sound like a tidy strategic campaign. It wasn't. It was 57 consecutive nights of terror that redefined what a city could actually survive.

The Myth of the "Blitz Spirit"

We love the image of the stoic Londoner sipping tea in a ruined kitchen. It makes for a great postcard. But if you talk to the historians who have actually combed through the Mass-Observation diaries from 1940, like the legendary Angus Calder, you get a much messier picture. People weren't just "keeping calm and carrying on." They were exhausted. They were often terrified. There was a massive spike in psychiatric admissions, though the government tried to keep those numbers quiet.

Looting was rampant. That's the part people hate to talk about. When a house was blown open, it wasn't always neighbors helping neighbors; sometimes it was people helping themselves to the silver before the dust had even settled. Crime didn't stop because the Luftwaffe was overhead. If anything, the blackout was a predator's paradise.

Honestly, the "Blitz Spirit" was partly a very clever, very necessary propaganda tool cooked up by the Ministry of Information. They needed the Americans to see a defiant Britain so they’d send help. It worked. But the reality was a mix of incredible bravery and total, grinding desperation.

The Night the City Almost Melted

December 29, 1940. It’s often called the Second Great Fire of London. This wasn't just a high-explosive raid; it was an incendiary attack designed to create a firestorm. Over 100,000 firebombs fell on the square mile of the City of London.

👉 See also: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

The water pressure failed. The tide was out on the Thames, so the fireboats couldn't get a good suction. Think about that for a second. You have the most iconic skyline in the world turning into a literal furnace because the moon moved the water away at the wrong time.

St. Paul’s Cathedral stood in the middle of it all. Prime Minister Winston Churchill famously sent a message saying "St. Paul’s must be saved at all costs." Why? Because if that dome fell, the morale of the country would have fallen with it. Volunteer firewatchers, some of them barely out of their teens, crawled across the roof of the cathedral to kick incendiary bombs off the lead before they could burn through. It stayed up. Everything around it burned, but the dome remained.

Where People Actually Slept

The government actually banned people from using the Underground stations as shelters at first. Can you believe that? They were worried about "deep shelter mentality"—the idea that if people went down there, they’d never come out to go to work.

The public basically staged a sit-in. They bought tickets, went down to the platforms, and just stayed there. Eventually, the authorities gave up and started installing bunks and chemical toilets. By 1941, about 150,000 people were sleeping on the tracks every night.

- It was loud.

- The smell was a mix of sweat, damp wool, and disinfectant.

- Rats were a constant.

- You’d have a wealthy banker sleeping three feet away from a dockworker’s family.

Outside of the "Tube," you had the Anderson shelters. These were basically corrugated steel holes in the backyard. They were cold. They flooded constantly. If you lived in an apartment—or a "flat"—you were basically out of luck unless you went to a communal brick shelter, which were notorious for being death traps if they took a direct hit.

✨ Don't miss: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

The Science of the "Scream"

The Germans used the Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers during parts of the bombing of London WWII, which were fitted with "Jericho Trumpets." These were propellers that made a terrifying wailing sound as the plane dove. It served no tactical purpose other than to scare the living daylights out of people on the ground. It was psychological warfare in its purest form.

Later in the war, the terror evolved. By 1944, Londoners faced the V-1 "Doodlebug." This was an early cruise missile. It had a pulsejet engine that made a very specific chug-chug-chug sound. The terrifying part wasn't the noise, though. It was the silence. When the engine cut out, you had about 12 seconds before it hit the ground. People would freeze, staring at the sky, just praying they weren't the ones under it when the sound stopped.

The Economic Scars

We talk about the lives lost—roughly 43,000 civilians in the Blitz alone—but the physical destruction changed the DNA of London forever. Over a million houses were damaged or destroyed.

This is why London looks the way it does today. You’ll be walking down a street of beautiful 19th-century Victorian terraces and suddenly, there’s a block of 1960s concrete apartments. That’s a "bomb gap." That’s where a 500kg Luftwaffe bomb landed in 1940. The city is a patchwork quilt of survival.

The cost was astronomical. Britain was basically bankrupt by the end of it. The rubble from the London docks was actually shipped across the Atlantic as "ballast" in empty supply ships and ended up being used as landfill in New York City. There’s a section of Manhattan’s FDR Drive built on the remains of Bristol and London.

🔗 Read more: Typhoon Tip and the Largest Hurricane on Record: Why Size Actually Matters

Why the Bombing of London WWII Still Matters

It’s easy to look back at 80-year-old black-and-white photos and feel detached. But the bombing of London WWII was the first time a modern, global city was systematically dismantled from the air. It set the precedent for everything that came after, from Dresden to the Blitz on Tokyo.

It also changed the social fabric of the UK. When the wealthy were bombed out of their mansions and forced to share shelters with the poor, the class barriers started to crack. It led directly to the creation of the National Health Service (NHS) and the modern welfare state. People decided that if they could die together in the streets, they should be able to live together with a basic level of dignity.

Essential Resources for Further Research

If you want to move beyond the textbook version of these events, these are the gold standards for historical accuracy:

- The Imperial War Museum (IWM) London: They hold the original sound recordings of the air raid sirens and the most extensive collection of civilian gas masks and shelter equipment.

- The National Archives at Kew: This is where the "Bomb Census" maps are kept. You can actually see exactly where every single bomb fell on your specific street.

- "The Blitz: The British Under-Fire" by Juliet Gardiner: This is widely considered the most human-centric history of the period, using thousands of first-hand accounts.

- The Museum of London Docklands: Essential for understanding why the East End took the brunt of the damage (it was the heart of the shipping industry).

Practical Steps for History Buffs

If you’re visiting London or researching the era, don't just go to the big monuments.

- Look for the "Shrapnel Scars": Walk past the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. The walls are still pockmarked with holes from a 1940 blast. They left them there on purpose.

- Visit the Churchill War Rooms: It’s expensive, but seeing the actual map room where they tracked the incoming raids is a surreal experience.

- Check "Bombsight": There is an online project called Bomb Sight that mapped every bomb dropped during the Blitz between Oct 1940 and June 1941. You can type in an address and see the destruction.

- St. Clement Danes: This is the "Central Church of the Royal Air Force." It was gutted by fire in 1941 and rebuilt. The floor is made of slate from various RAF stations, and it serves as a living memorial.

The bombing of London wasn't just a military campaign. It was a 2,000-year-old city being forced to reinvent itself in real-time. The scars are still there if you know where to look.