You’ve probably seen the instructions on the back of a cake mix box. There is always that little section for "high altitude" baking. Most people ignore it. But if you’ve ever tried to boil an egg in a cabin at 10,000 feet, you know something feels... off. The water is bubbling furiously, yet the egg stays runny for way longer than it should. It’s annoying. It’s also physics.

The boiling point of water at various pressures isn't just a classroom trivia fact; it's a fundamental rule of thermodynamics that dictates how we cook, how power plants generate electricity, and how we stay alive in extreme environments. We are taught in grade school that water boils at 212°F (100°C). That is a lie—or at least, a very narrow truth. It only boils at that temperature if you are standing at sea level, like on a beach in Miami or San Diego. Move even a few hundred feet up or down, and the rules change instantly.

The Push and Pull of Vapor Pressure

To understand why this happens, you have to think about what boiling actually is. It isn't just "getting water hot." Boiling is a literal battle between internal energy and external weight.

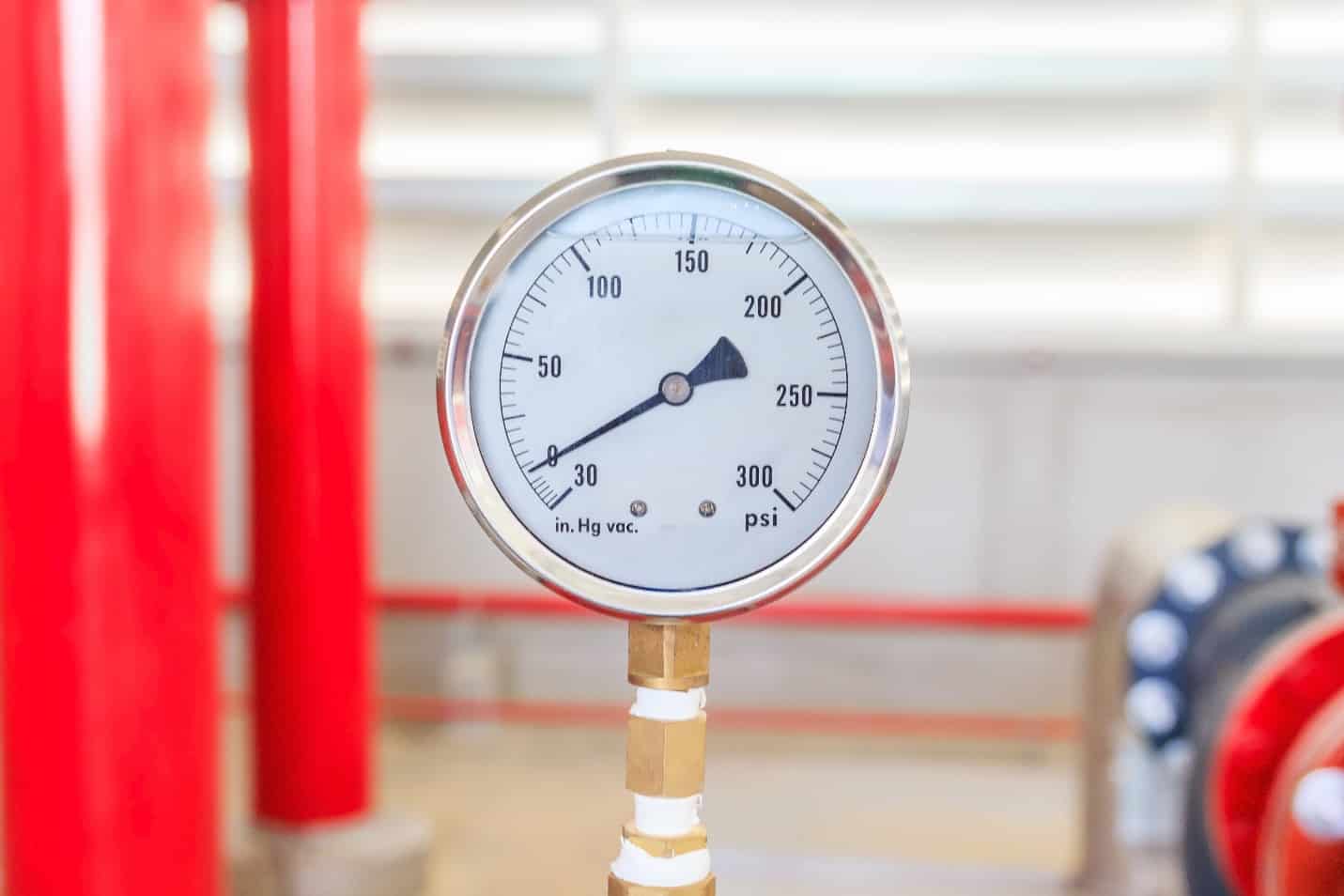

Think of the air around you as a heavy blanket. Even though we don't feel it, the atmosphere is heavy. It's pressing down on every square inch of your body—and your pot of water—with about 14.7 pounds of force per square inch (psi) at sea level. This is what we call 1 atmosphere (atm). Inside the water, molecules are buzzing around. As you add heat, they buzz faster. Eventually, they want to break free and turn into gas. But they can’t. The weight of the air is literally holding them down in liquid form.

Boiling only happens when the "vapor pressure" of the water (the outward push of the molecules) equals the "atmospheric pressure" (the inward push of the air). If you lower the air pressure, the water doesn't need as much heat to win the fight. It can break free into steam at a much lower temperature.

Life at the Extremes: Everest vs. The Deep Sea

Let's look at some real-world numbers because the scale of this is actually wild. If you were standing on the summit of Mount Everest, the atmospheric pressure is roughly one-third of what it is at sea level. Because there is so much less "blanket" pushing down on the water, the boiling point of water at various pressures drops significantly. Up there, water boils at about 160°F (71°C).

That sounds fine until you try to make tea. 160°F isn't hot enough to properly extract flavors from tea leaves, and it’s certainly not hot enough to kill certain bacteria quickly. You could have a pot of "boiling" water on Everest that you could almost stick your hand in without getting a third-degree burn (though I wouldn't recommend it).

Now, flip the script.

👉 See also: Dave's Hot Chicken Waco: Why Everyone is Obsessing Over This Specific Spot

If you go to the bottom of the ocean, near hydrothermal vents, the pressure is staggering. At these depths, the pressure can be hundreds of times higher than at the surface. Down there, water can reach temperatures of 700°F (370°C) without ever turning into steam. It stays liquid because the sheer weight of the ocean prevents the molecules from flying apart. This is "superheated" water, and it’s the reason why unique ecosystems can thrive in the pitch black of the abyss.

The Science of the Pressure Cooker

You might have a pressure cooker or an Instant Pot in your kitchen. These devices are basically "sea level simulators" on steroids. By trapping steam inside a sealed pot, the device artificially increases the pressure.

As the water heats up and turns to steam, the steam has nowhere to go. This builds up the internal pressure to about 15 psi above atmospheric pressure. In this high-pressure environment, the boiling point of water jumps to about 250°F (121°C).

This is the secret.

Food cooks faster not because of the pressure itself, but because the water (and steam) is significantly hotter than it could ever be in an open pot. You're basically hacking physics to force heat into a pot of beans or a tough cut of meat at temperatures that would be impossible on a standard stovetop.

Predicting the Change: The Clausius-Clapeyron Equation

For the nerds in the room, we don't just guess these numbers. Scientists use something called the Clausius-Clapeyron relation. It's a formula that characterizes the phase transition between a liquid and a gas.

Essentially, it looks like this:

$$\ln\left(\frac{P_2}{P_1}\right) = \frac{-\Delta H_{vap}}{R} \left(\frac{1}{T_2} - \frac{1}{T_1}\right)$$

✨ Don't miss: Dating for 5 Years: Why the Five-Year Itch is Real (and How to Fix It)

In this equation:

- $P$ represents pressure.

- $T$ represents temperature in Kelvin.

- $\Delta H_{vap}$ is the enthalpy of vaporization (the energy needed to turn the liquid to gas).

- $R$ is the ideal gas constant.

While you don't need to do the math to boil pasta, this equation is the backbone of chemical engineering. It's how we design steam turbines for power plants and how we ensure that airplane engines don't fail when the pressure drops at 35,000 feet.

Why Altitude Sickness and Cooking Go Hand in Hand

If you live in Denver (the Mile High City), you’re at about 5,280 feet. At this elevation, water boils at roughly 202°F (94°C). This 10-degree difference might not seem like much, but it changes the chemistry of baking.

Leavening gases (like the air bubbles produced by baking powder) expand more quickly because there is less pressure holding them back. If you don't adjust your recipe, your cake will rise too fast, the bubbles will pop, and the whole thing will collapse into a dense, sad mess. Most high-altitude bakers add a bit more water—because it evaporates faster—and slightly increase the oven temperature to "set" the structure of the bread or cake before the low pressure ruins it.

The Vacuum Effect: Boiling Without Heat

Here is the weirdest part: you can make water boil without heating it up at all.

If you place a glass of room-temperature water inside a vacuum chamber and start sucking the air out, you are lowering the atmospheric pressure. Eventually, the pressure drops so low that it matches the vapor pressure of the room-temperature water.

Suddenly, the water starts bubbling violently. It looks like it’s hot, but it’s actually still 70°F. If you kept the vacuum running, the boiling would actually cause the water to lose energy (evaporative cooling), and the water would eventually freeze while it’s still "boiling." Physics is trippy like that.

🔗 Read more: Creative and Meaningful Will You Be My Maid of Honour Ideas That Actually Feel Personal

Real-World Applications You Probably Missed

We see the boiling point of water at various pressures at work in industries you’d never expect.

- Autoclaves: Hospitals use these to sterilize surgical tools. By cranking the pressure up, they get water hot enough to kill even the most heat-resistant bacterial spores.

- Freeze-Drying: Your camping food or "space ice cream" is made by freezing food and then lowering the pressure so much that the ice turns directly into gas (sublimation), skipping the liquid phase entirely.

- Power Generation: Nuclear and coal plants use high-pressure steam to spin turbines. The higher the pressure, the more energy the steam carries, making the plant more efficient.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

So, how does this actually help you in the real world?

First, if you’re moving to a higher elevation, buy a thermometer. Don't trust the "boiling" bubbles; check the actual temperature. If your water is only hitting 200°F, you need to simmer your pasta for an extra minute or two.

Second, if you’re using a pressure cooker, remember that the "natural release" method is essentially a slow descent in pressure. If you "quick release," you’re causing a sudden drop in pressure, which makes the liquid inside boil violently. This can toughen up meat or spray starchy water all over your kitchen.

Lastly, respect the steam. Steam at 250°F from a pressure cooker carries significantly more latent heat than steam at 212°F. It will cause a much more severe burn in a shorter amount of time.

Understanding the relationship between pressure and temperature makes you a better cook and a more informed inhabitant of this pressurized rock we call Earth. Whether you're at the beach or in the Rockies, the laws of thermodynamics are always in the pot with you.

Next Steps for Mastering Thermal Dynamics:

To get the most out of this knowledge, start by calibrating your kitchen. Use a digital thermometer to find the exact boiling point in your home. Once you have that baseline, compare it to a standard altitude chart to see exactly how your local atmospheric pressure deviates from the "standard" sea-level model. If you're a baker, begin adjusting your hydration levels by 5-10% to account for the faster evaporation rates found at even moderate altitudes.