You’ve probably stepped over a million of them without a second thought. Ants are everywhere. But if you actually stop and look at the body of an ant, you’re looking at one of the most successful engineering projects in the history of the planet. It’s a tank. It’s a chemical factory. It’s a heavy-lift crane. All stuffed into a package that weighs less than a grain of salt.

Honestly, we underestimate them.

Think about it. An ant can fall from a skyscraper and walk away like nothing happened. They don’t have lungs, yet they breathe. They don’t have ears, yet they "hear" everything. Evolution didn't just make them small; it made them optimized.

The Hard Shell Strategy: Living Inside an Exoskeleton

Humans are built around a central stick of bone. Ants? They flipped the script. The body of an ant is encased in a chitinous exoskeleton. This isn't just a skin; it's a structural masterpiece made of a tough, nitrogen-rich polysaccharide. It acts as armor, a waterproof seal, and a mounting point for muscles all at once.

Because the muscles are attached to the inner walls of this "armor," they get incredible leverage. This is why an ant can lift 50 times its own body weight. Imagine picking up a literal truck with your teeth. That's the daily reality for a common pavement ant (Tetramorium caespitum).

But there’s a catch.

Exoskeletons don’t grow. This means ants have to molt during their larval stages, but once they reach adulthood, that’s it. They are locked into that size. This rigid shell also limits how big they can get. If an ant were the size of a Golden Retriever, its legs would likely snap under the pressure of its own armor, or it would simply suffocate.

Anatomy of the Three Segments

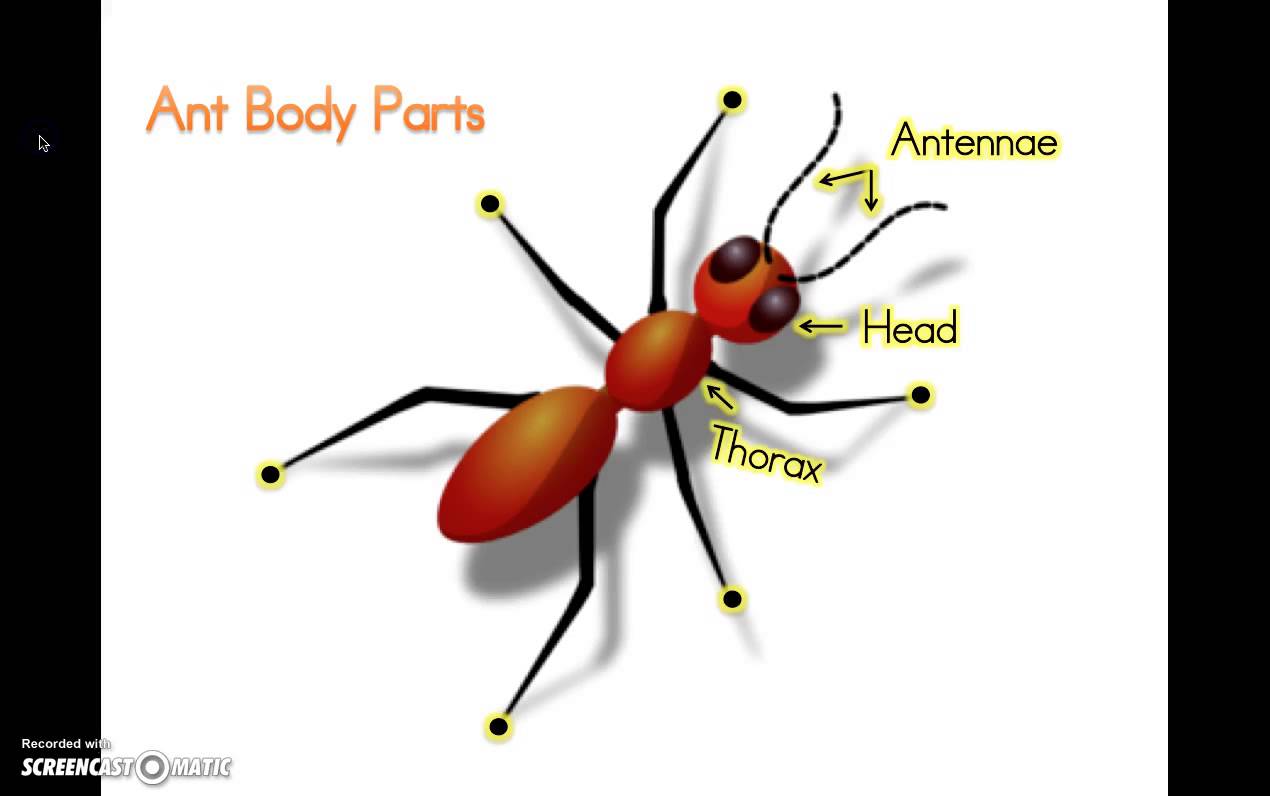

The body of an ant is divided into three distinct parts: the head, the mesosoma (the chest or thorax), and the metasoma (the abdomen or gaster).

The Control Center: The Head

The head is where the magic happens. You’ll notice two massive mandibles. These aren't just for eating. They are pliers, scissors, and weapons. In some species, like the trap-jaw ant (Odontomachus), these jaws can snap shut at speeds of 145 miles per hour. That’s the fastest self-powered strike in the animal kingdom.

Then you have the antennae.

Don't call them feelers. They are way more than that. They are sophisticated chemical sensors. An ant "smells" the world in 3D using these jointed stalks. They pick up pheromone trails left by sisters, identify intruders, and even sense the vibration of the ground.

And the eyes? Most ants have compound eyes made of numerous tiny lenses called ommatidia. They aren't seeing 4K video. It’s more like a grainy, motion-sensitive mosaic. Interestingly, many species also have three tiny "simple" eyes on top of their heads called ocelli, which detect light levels and help with navigation using the sun.

The Engine Room: The Mesosoma

The middle section is basically a box of muscles. This is where the six legs are attached. Each leg has three joints and ends in a tiny claw. These claws, combined with sticky pads called arolia, allow ants to walk upside down on glass or scale a vertical brick wall without breaking a sweat.

If it’s a queen or a male, this is also where the wings attach. But for your average worker, it's just a powerhouse of locomotion.

The Backend: The Gaster

The gaster is the big bulbous part at the end. This is where the vital organs live—the heart (which is really just a long tube that pumps clear hemolymph), the digestive system, and the chemical weapons. Many ants have a stinger back here. Others, like Formica ants, have an acidopore that sprays formic acid.

Ever been "bitten" by a wood ant and felt a sting? They didn't just bite you; they bit you to hold on, then curled their gaster forward to spray acid into the wound. It's brutal.

Breathing Through Their Skin (Sorta)

Ants don't have lungs. They don't have a diaphragm. They don't pant.

Instead, the body of an ant is riddled with tiny holes called spiracles. These are located along the sides of the thorax and abdomen. Oxygen simply drifts into these holes and travels through a network of tiny tubes called tracheae, delivering gas directly to the cells.

It’s efficient, but only at a small scale. This is actually the main reason ants aren't the size of humans. Passive oxygen diffusion only works over very short distances. If an ant were huge, the oxygen would never reach the center of its body. We’d be living in a very different world if ants could breathe like us.

The Social Stomach: Sharing is Caring

One of the weirdest parts of the body of an ant is the crop, often called the "social stomach."

Ants actually have two stomachs. The first is for their own digestion. The second is a storage tank. When an ant finds a sugary snack, she fills up her crop. When she returns to the nest, she can regurgitate that liquid to feed her sisters. This process is called trophallaxis.

It’s not just about food, though. Trophallaxis is a communication network. They pass hormones and chemical signals through this shared liquid. It’s basically a liquid internet that keeps the entire colony on the same page.

Why the Body of an Ant is a Survival Masterpiece

Every single hair (setae) on an ant's body serves a purpose. Some detect wind. Others keep the ant clean. Some species, like the Saharan Silver Ant, have specialized hairs that reflect heat, allowing them to survive in 120-degree deserts that would kill almost anything else.

Their circulatory system is "open." Their "blood" (hemolymph) just sloshes around inside the body cavity, bathing the organs directly. This makes them incredibly resilient to internal pressure changes and physical trauma. You can't really give an ant a "bruise" in the way we think of them.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Observer

If you want to appreciate the body of an ant in the real world, here is how you can actually see these features in action:

- Get a 10x Macro Lens: You don't need a microscope. A cheap clip-on macro lens for your phone will reveal the spiracles and the individual facets of the compound eyes.

- Watch the Antennae: Place a small drop of honey near an ant trail. Watch how the first ant to find it uses its antennae to "tap" the liquid and then frantically taps the ground to lay a pheromone trail back home.

- Identify the "Waste": Look for a "midden" (an ant garbage dump) near a nest. You’ll see discarded exoskeletons of prey, showing how effective their mandibles are at stripping protein.

- Respect the Formic Acid: If you find a large mound of wood ants, hover your hand (don't touch!) a few inches above it. You might smell a sharp, vinegar-like scent. That's the collective chemical output of their gasters.

The body of an ant is a testament to the idea that bigger isn't always better. They have survived for over 140 million years, outlasting the dinosaurs and surviving multiple mass extinctions. They did it by being small, armored, and incredibly specialized. Next time you see one on your kitchen counter, maybe give it a second of respect before you reach for the spray. It's a marvel of biological engineering.