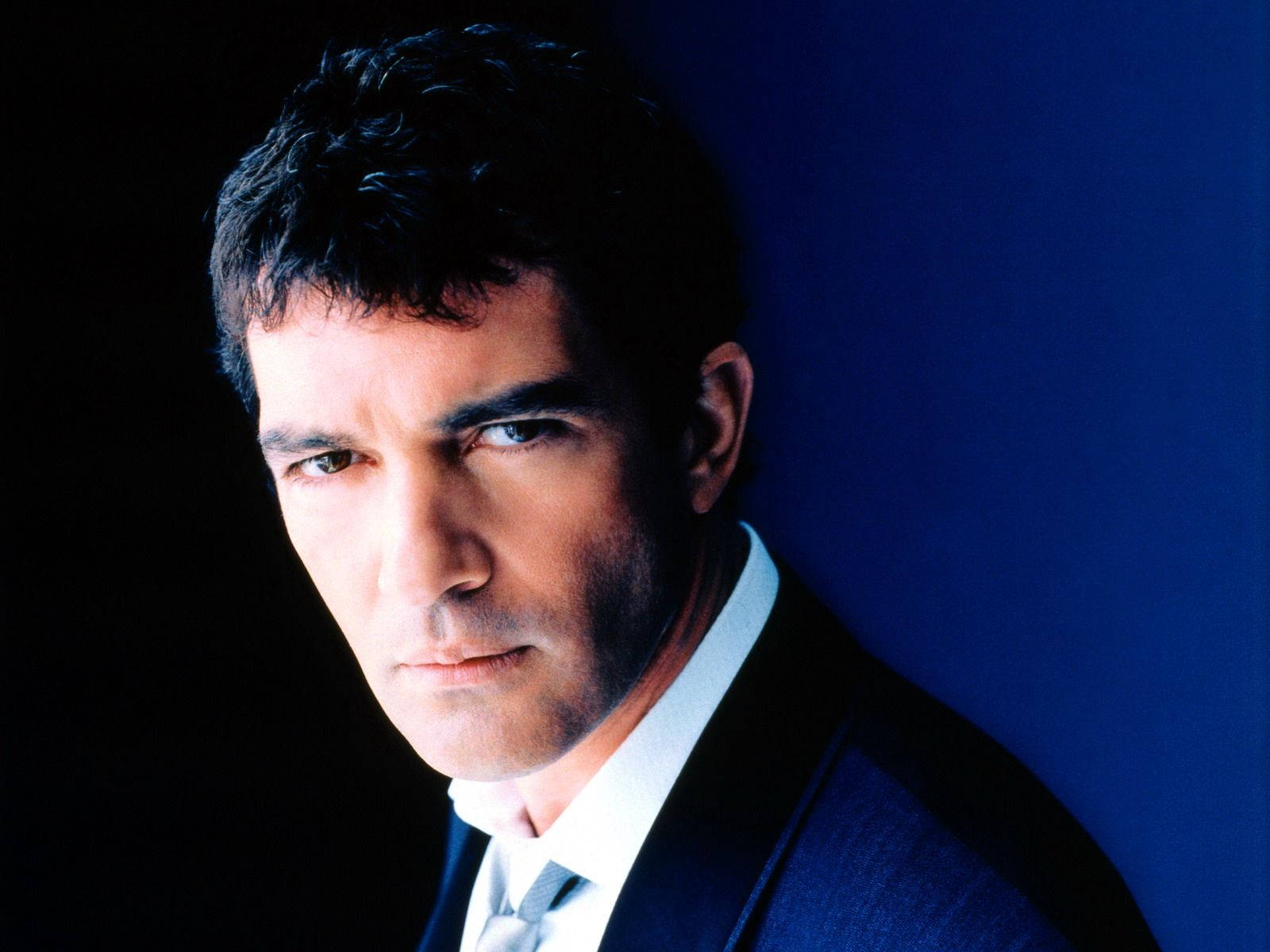

It’s 2001. Antonio Banderas is arguably at the peak of his Hollywood powers, coming off the massive success of The Mask of Zorro and The 13th Warrior. Then he makes a movie about a dead body found in Jerusalem that might—just might—be the remains of Jesus Christ. Honestly, it’s a miracle the film didn't cause a massive international incident at the time. The Body Antonio Banderas movie is one of those weird, forgotten relics of the early 2000s that attempted to blend Indiana Jones-style archaeology with heavy-duty theological questioning.

It didn't exactly set the box office on fire. Critics were, let’s say, less than kind. But if you watch it today, there’s a nuance there that most people missed because they were too busy comparing it to the high-octane blockbusters of the era.

What Actually Happens in The Body?

The plot is basically every Vatican official's worst nightmare. An Israeli archaeologist, played by Olivia Williams, uncovers a skeleton in a tomb that dates back to the first century. It shows signs of crucifixion. There's a clay jar nearby with an inscription that suggests this isn't just any guy; it could be the "King of the Jews."

Banderas plays Father Matt Gutierrez. He’s a Jesuit priest, but he’s also a former intelligence officer. Think of him as a man of God with the tactical skills of a soldier. The Vatican sends him to Jerusalem to investigate, or more accurately, to debunk the find. Because if that skeleton is Jesus, the entire foundation of Christianity—the Resurrection—is a lie.

It’s a heavy premise.

The movie focuses on the friction between Gutierrez’s faith and the cold, hard scientific evidence Williams’ character presents. It’s a slow burn. It isn't an action movie, though the marketing tried to sell it as one. You've got Mossad involved, Palestinian extremist groups, and the shadowy politics of the Catholic Church all colliding in a dusty, tense Jerusalem.

Antonio Banderas and the Jesuit Dilemma

Banderas gives a surprisingly restrained performance here. We’re used to him being the "Latin Lover" or the swashbuckling hero, but in The Body, he’s internalized. He looks tired. He looks like a man who is terrified that his life's work is based on a myth.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

The chemistry between him and Olivia Williams is interesting because it isn't overtly romantic—thankfully. It’s more of an intellectual wrestling match. She represents the "how" and he represents the "why."

- The Scientist: Dr. Sharon Golban (Williams) doesn't care about the religious implications. She cares about the carbon dating and the osteology.

- The Priest: Father Gutierrez (Banderas) is fighting for the survival of a global faith.

Why the Film Failed to Hit Big

Part of the reason The Body faded into obscurity is the timing. It came out just a few years before The Da Vinci Code book became a global phenomenon. In 2001, audiences weren't quite primed for "religious conspiracy thrillers" in the way they would be by 2004.

The pacing is also... deliberate.

Director Jonas McCord, who also wrote the screenplay based on Richard Sapir's novel, spent a lot of time on dialogue. If you’re expecting car chases, you’ll be disappointed. If you want to see two people arguing about the nature of belief in a dark tomb, you're in the right place.

The film also suffered from an identity crisis. Was it a political thriller about the Middle East? A religious drama? A detective story? It tried to be all three and, honestly, kinda stumbled over its own feet. The ending, which I won't spoil here, is actually much more cynical and thought-provoking than your standard Hollywood fare. It doesn't give you a neat little bow.

Real Archaeology vs. Movie Magic

Let’s talk facts. The movie mentions the "shroud" and specific burial customs of the Second Temple period. While the film is fiction, it draws heavily on real archaeological tensions in Jerusalem.

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

In the real world, the "James Ossuary" or the "Talpiot Tomb" are actual discoveries that caused similar media firestorms. When someone finds a box that says "Jesus, son of Joseph," the world stops spinning for a second. The Body captures that specific brand of panic perfectly.

Historians often point out that the Romans crucified thousands of people. Finding a crucified skeleton isn't necessarily a "gotcha" for Christianity. But the film leans into the specific markers—the lack of broken legs, the crown of thorns evidence—to make the stakes feel sky-high.

The Political Backdrop You Might Have Missed

One thing that makes The Body Antonio Banderas movie stand out is how it depicts Jerusalem. It doesn't treat the city like a postcard. It shows the grit, the soldiers, the barbed wire, and the constant, vibrating tension between different factions.

The skeleton becomes a political football.

- The Israeli government wants to use it as leverage.

- Palestinian groups see it as a threat to the status quo.

- The Vatican just wants it to go away.

This is where the film is actually quite smart. It shows that even if you found the "truth," the world might be too broken to handle it.

Why You Should Revisit It

If you can find a copy—it’s often buried on deep-catalog streaming services—it’s worth a watch for the atmosphere alone. The cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond (who did Close Encounters of the Third Kind) is gorgeous. He makes the limestone of Jerusalem look both holy and suffocating.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

It’s also a great look at Banderas during his transition from "action star" to "prestige actor." He was trying to do something different here. He wasn't just leaning on his charisma; he was trying to play a man whose soul was cracking open.

Actionable Takeaways for Movie Buffs

If you’re planning to track down The Body, keep these things in mind to get the most out of the experience:

- Read up on the Talpiot Tomb: Knowing the real-life controversies surrounding "Jesus’s family tomb" makes the stakes in the movie feel much more grounded in reality.

- Watch for the symbolism: The film uses light and shadow specifically to denote Gutierrez’s state of mind. When he’s in the dark tombs, he’s often the most "enlightened" about the truth.

- Contrast it with The Da Vinci Code: It’s fascinating to see how The Body handles similar themes with a much more somber, less "escapist" tone than Dan Brown’s work.

- Check out the book: The novel by Richard Sapir is actually a bit more of a thriller than the movie. If the film feels too slow for you, the source material might be your speed.

Ultimately, The Body is a film about the danger of certainty. Whether you’re a person of faith or a person of science, the movie suggests that the truth is usually a lot messier than we want it to be. It’s not a masterpiece, but it’s an ambitious, intellectual experiment that deserves more than being a footnote in Antonio Banderas’s IMDb page.

Check the "available to rent" sections of your favorite streamers. Often, these mid-budget thrillers from the early 2000s are the perfect Friday night find when you’re tired of the latest CGI-heavy superhero flick. Go in with an open mind and don't expect a chase scene every ten minutes. You might find that the questions it asks stick with you much longer than the plot itself.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

To get the full context of this era of religious thrillers, watch The Body back-to-back with the 1999 film Stigmata. While The Body focuses on the archaeological and political side of religious crisis, Stigmata handles the supernatural and conspiratorial aspects of the Vatican. Together, they provide a perfect snapshot of the pre-9/11 anxiety regarding ancient secrets and the authority of the Church. You should also look into the career of director Jonas McCord, who has often focused on projects that bridge the gap between historical fact and dramatic fiction. Reading the original 1983 novel by Richard Sapir can also clarify several of the more complex theological arguments that were trimmed for the film's runtime.