You've probably seen it hanging in a doctor's office or taped to a gym wall—that colorful, blocky grid known as the bmi height and weight chart. It looks official. It feels definitive. But honestly, most people stare at those little squares of green, yellow, and red with a mix of anxiety and total confusion. We’ve been conditioned to think that if our finger lands in the "overweight" box, we’re somehow failing at health.

It’s just math. That’s all BMI is. Specifically, it is your weight in kilograms divided by your height in meters squared.

Invented in the 1830s by a Belgian mathematician named Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet, the formula wasn't even meant for doctors. Quetelet was a social scientist trying to define the "average man" for the sake of government statistics. He explicitly stated it shouldn't be used to judge individual health. Fast forward nearly 200 years, and here we are, using a nineteenth-century math equation to determine if we’re "healthy" or not.

What Your BMI Height and Weight Chart Isn’t Telling You

The biggest flaw in the bmi height and weight chart is that it cannot tell the difference between five pounds of marble-hard muscle and five pounds of jiggly body fat. Muscle is much denser than fat. This is why a professional rugby player or a dedicated bodybuilder might stand 6 feet tall, weigh 230 pounds, and be labeled "obese" by the chart. Their body fat percentage might be in the single digits, but the math doesn't care. The math only sees the scale.

Actually, there's a term for the opposite problem: "Normal Weight Obesity." You might know it as "skinny fat." This happens when someone's BMI falls perfectly within the "healthy" range of 18.5 to 24.9, but they have very little muscle mass and a high percentage of visceral fat—the dangerous stuff that wraps around your organs. For these individuals, the chart provides a false sense of security. They might be at a high risk for Type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular issues, yet the chart gives them a green light.

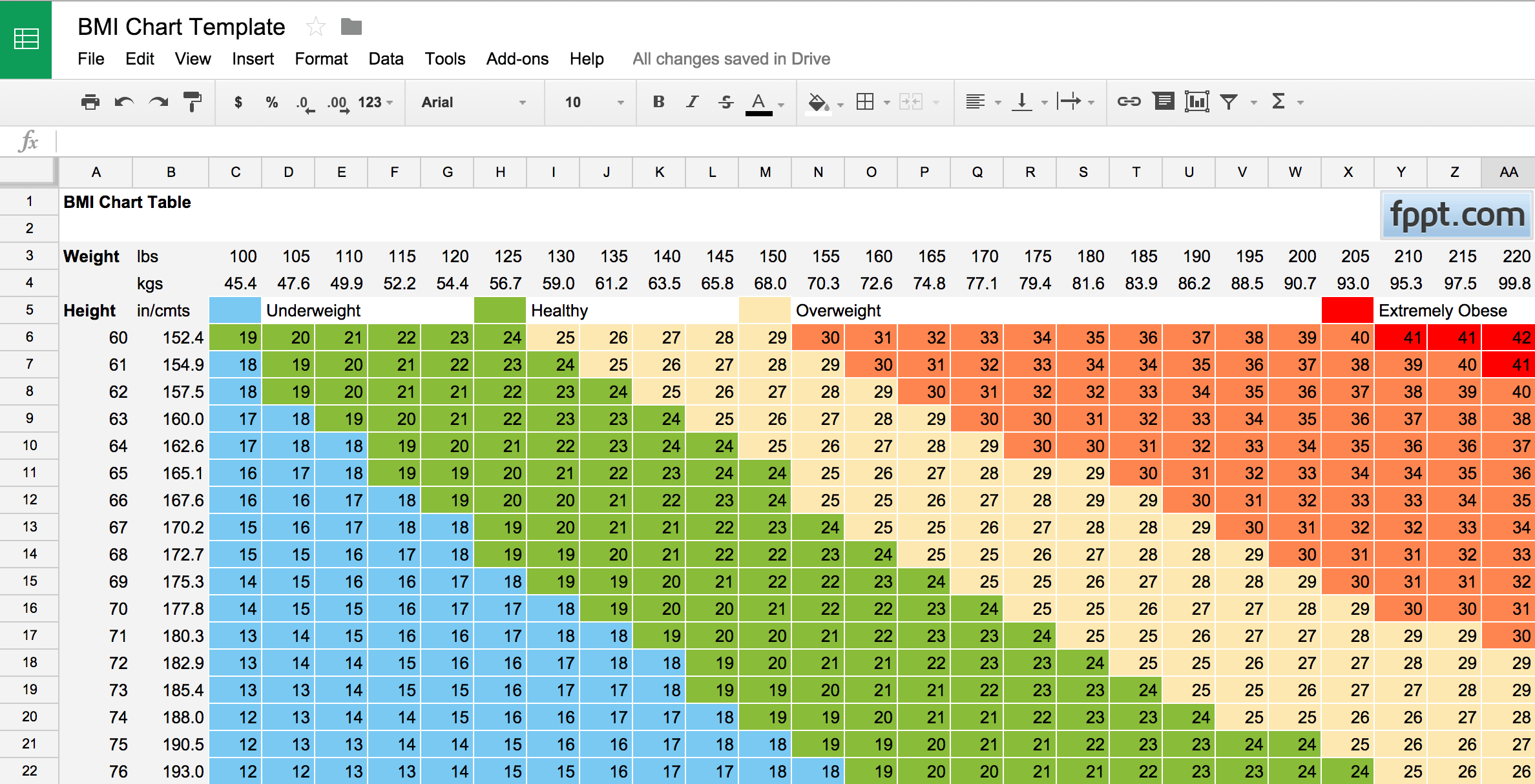

Standard BMI categories generally look like this:

- Under 18.5 is Underweight

- 18.5 to 24.9 is Healthy Weight

- 25.0 to 29.9 is Overweight

- 30.0 and above is Obese

But these numbers are slippery. In 1998, the National Institutes of Health changed the "overweight" threshold from 27 to 25. Overnight, millions of Americans who were considered "normal" suddenly became "overweight" without gaining a single ounce. This shift was controversial, with some experts, including those from the Harvard School of Public Health, noting that while it aligned with World Health Organization standards, it also drastically changed how we perceive public health "epidemics."

Why Bone Density and Ethnicity Change the Math

We aren't all built from the same blueprint. The bmi height and weight chart assumes a Caucasian-centric body type, which creates massive inaccuracies for different ethnic groups. Research has shown that people of Asian descent often have a higher risk of heart disease and diabetes at lower BMI levels. For this reason, many health organizations in Asia use a "healthy" cutoff of 23 instead of 25.

On the flip side, studies on African American populations—particularly women—suggest that the health risks associated with a higher BMI don't always kick in at the same points as they do for white populations. Bone density plays a role here too. Some people simply have a larger frame. If you have "heavy bones," your BMI will naturally be higher, but that doesn't mean you're carrying excess adipose tissue.

The Problem with Age

As we get older, our bodies change. It's called sarcopenia—the natural loss of muscle mass as we age. For seniors, a slightly higher BMI might actually be protective. It’s known as the "obesity paradox." In older adults, having a bit of extra weight can provide a nutritional reserve during illness or a "cushion" in the event of a fall. A 75-year-old with a BMI of 27 might actually be in a better position for longevity than one with a BMI of 20.

Better Ways to Measure Progress

If the bmi height and weight chart is so flawed, why do we still use it? Because it’s cheap. It’s fast. You don’t need a blood test or an MRI to calculate it. But if you really want to know what's going on with your body, you have to look deeper.

✨ Don't miss: Weight Gain with Birth Control: What Most People Get Wrong

Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) is often a much better predictor of health. To do this, you measure the smallest part of your waist and the widest part of your hips. Divide the waist by the hip. For men, a ratio of 0.90 or less is great; for women, 0.85 or less is the target. This matters because it tracks where your fat is stored. "Apple-shaped" people who carry weight in their midsection are at a much higher risk for metabolic syndrome than "pear-shaped" people who carry weight in their hips and thighs.

Then there’s the Waist-to-Height Ratio. This one is even simpler. Your waist circumference should ideally be less than half your height. If you are 70 inches tall, your waist should be 35 inches or less. It’s surprisingly accurate across different ages and ethnicities.

Modern Tech: Beyond the Grid

If you want the gold standard, you’re looking at a DEXA scan. It’s basically a low-level X-ray that maps out exactly where your fat, muscle, and bone are. It’s what pro athletes use. Or, for something more accessible, high-quality "smart scales" use bioelectrical impedance. They send a tiny, unfelt electric pulse through your body. Since water, fat, and muscle conduct electricity differently, the scale can give you a rough estimate of your body fat percentage. It’s not perfect, but it’s a lot more useful than a static height/weight table.

🔗 Read more: Brain fog vitamin deficiency: Why your brain feels like it is buffering

Practical Steps to Use BMI Without Losing Your Mind

Don't throw the bmi height and weight chart in the trash just yet. It’s a tool—a crude one, sure, but a tool nonetheless. It’s a starting point for a conversation with your doctor, not the final word on your health.

- Check your trends, not just the snapshot. If your BMI has jumped from 24 to 28 in a single year, that’s a signal to look at your lifestyle, regardless of whether you "feel" okay.

- Measure your waist. Buy a flexible measuring tape. If your BMI says "overweight" but your waist-to-height ratio is well within the healthy range, you can probably stop stressing about the chart.

- Focus on "Non-Scale Victories." How do your clothes fit? How is your energy? Can you climb a flight of stairs without getting winded? These markers matter infinitely more than a number on a nineteenth-century grid.

- Get a blood panel. A person with an "obese" BMI but perfect blood pressure, low triglycerides, and healthy blood sugar levels is often metabolically healthier than a thin person with "bad" numbers.

Health is a mosaic. The bmi height and weight chart is just one tiny, slightly blurry tile in that picture. If you use it as your only guide, you’re missing the forest for the trees. Look at your sleep, your stress, your movement, and your nutrition. Those are the levers you can actually pull. The chart is just a reference point, and honestly, a pretty outdated one at that.

Next Steps for Your Health Tracking

- Measure your waist-to-height ratio today: Use a simple piece of string to measure your height, then see if that string can go around your waist twice. If it can’t, it’s time to focus on metabolic health.

- Request a metabolic panel: At your next physical, ask your doctor to prioritize your A1C and lipid profile over your BMI reading.

- Audit your muscle mass: Focus on resistance training at least twice a week to ensure that any weight you carry is functional tissue rather than just stored energy.