January 15, 1947. Los Angeles was cold. Betty Bersinger was walking with her three-year-old daughter when she saw something in a vacant lot on Norton Avenue. She thought it was a discarded store mannequin. It wasn't. What she actually found was the bisected, drained, and posed body of Elizabeth Short. That moment sparked a media circus that hasn't stopped for nearly eighty years. When people search for a black dahlia murder picture, they're usually looking for the grainy, black-and-white crime scene photos that defined an era of noir horror. But these images aren't just morbid curiosities. They are forensic puzzles that have stumped the LAPD for generations.

The case is messy. Honestly, it’s a miracle any evidence survived the initial "investigative" phase.

The disturbing reality of the black dahlia murder picture

If you’ve seen the famous black dahlia murder picture from the vacant lot, you know it’s uncanny. The body was severed perfectly at the waist. This is known as a hemicorporectomy. It wasn't a hack job; it was surgical. This specific detail led investigators to believe the killer had medical training. Maybe a surgeon. Maybe a butcher. The precision is what makes the photos so chilling. You see the "Glasgow Smile"—incisions carved from the corners of the mouth to the ears. It's a haunting image of 1940s brutality that feels like it belongs in a fictional thriller, yet the bloodless white skin of Elizabeth Short proves it was very real.

Reporters actually beat the police to the scene. Think about that.

Before the detectives could even rope off the area, photographers from the Los Angeles Examiner were snapping shots. They even rearranged things for "better" angles. This is why some versions of the crime scene photos look slightly different—the press was literally moving evidence to get a more dramatic front-page spread. It’s gross. It’s unethical. But it’s the reality of 1940s tabloid journalism.

Why the photos look "clean"

One thing that confuses people looking at a black dahlia murder picture is the lack of blood. There’s almost none. The killer washed the body. They drained it of blood elsewhere and then transported it to the lot. This suggests the "crime scene" wasn't where the murder happened; it was just a stage. The way the arms were tucked and the legs were splayed—it was a performance.

✨ Don't miss: Chase From Paw Patrol: Why This German Shepherd Is Actually a Big Deal

The suspects hiding in the shadows

Over the years, names like George Hodel and William Heirens have been tossed around. George Hodel is the big one. His own son, Steve Hodel, a former LAPD detective, has spent years trying to prove his father did it. Steve points to specific photos found in his father's personal collection as proof. These photos show a woman who looks remarkably like Elizabeth Short. Are they the "missing" links? Maybe. But "looking like" someone isn't a DNA match.

The LAPD had over 150 suspects. Some were doctors. Some were creeps who just liked to confess to things they didn't do.

The sheer volume of people who claimed they killed her is staggering. It’s a phenomenon called "pathological confession." When a case gets this much press, people crawl out of the woodwork. They want the fame, even if it comes with a death sentence. It makes sorting through the actual evidence—the fingerprints, the letters sent to the press, the blurred faces in the background of a black dahlia murder picture—nearly impossible.

The "Black Dahlia" nickname

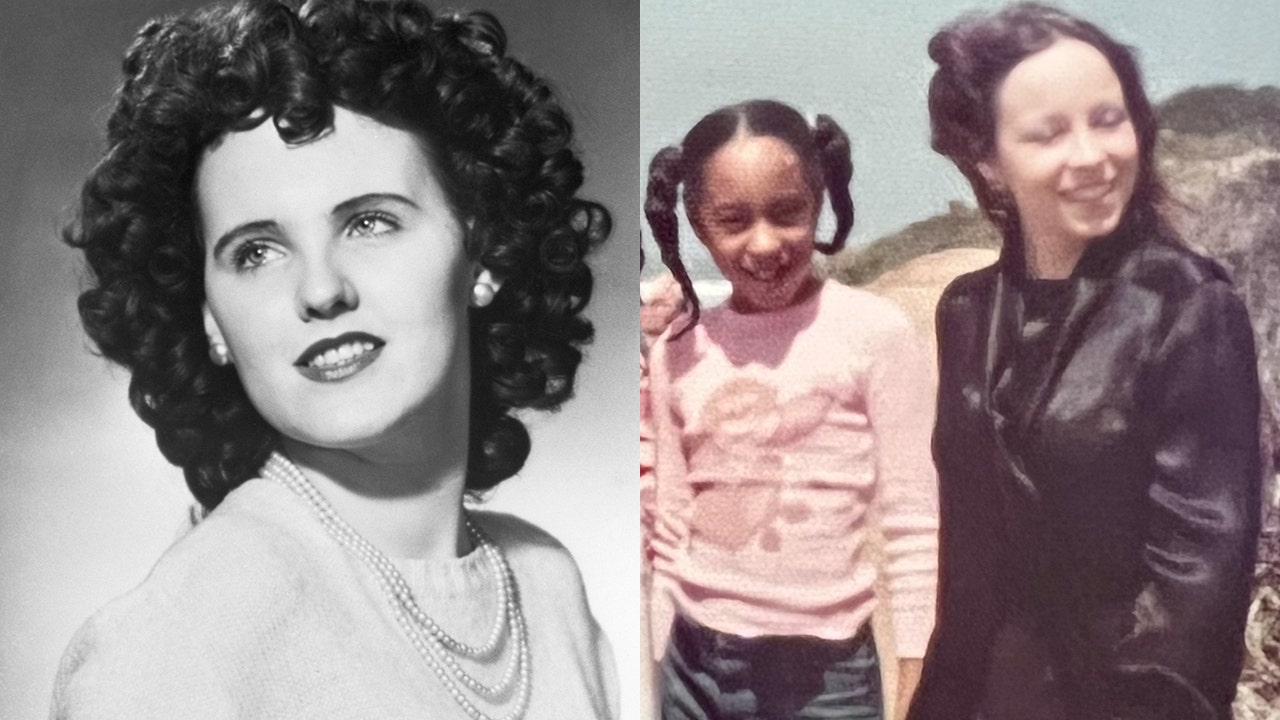

Elizabeth Short wasn't called the Black Dahlia while she was alive. That’s a myth. The name was a play on the movie The Blue Dahlia, which was out at the time. The press loved a good nickname. It sold papers. It turned a victim into a character. If you look at candid photos of Elizabeth before the murder, she’s just a young woman trying to make it in Hollywood. She was 22. She had bad teeth and liked to wear black. She wasn't a "femme fatale" from a movie; she was a girl from Massachusetts who ran out of luck in a town that eats people alive.

The forensic limitations of 1947

We didn't have DNA testing. We didn't have digital databases. We had fingerprints and blood typing.

🔗 Read more: Charlize Theron Sweet November: Why This Panned Rom-Com Became a Cult Favorite

- Fingerprints were lifted from the letters the killer sent to the Examiner.

- The letters were "cleaned" with gasoline, which destroyed most of the skin oils.

- The handwriting was disguised using cut-out newspaper clippings.

If this happened today, the killer would have been caught in 48 hours. Between CCTV, cell tower pings, and touch DNA, the "surgical" killer wouldn't have stood a chance. But in 1947? You could disappear into the fog of a smoggy LA morning and never be seen again. The black dahlia murder picture is a window into a time when the law was always three steps behind the criminal.

The role of the media

The Los Angeles Examiner didn't just report the news; they manipulated it. They called Elizabeth’s mother, Phoebe Short, and told her Elizabeth had won a beauty contest just to get information out of her. Once they had the "scoop," they told her the truth: her daughter was dead. That kind of cruelty is what fueled the frenzy. Every black dahlia murder picture published was a way to keep the public buying the next edition. They even published her autopsy details, which by today's standards would be a massive legal violation.

Modern interpretations and digital archives

Today, you can find the black dahlia murder picture in various archives, but many are censored or cropped. The original, unedited photos are kept in the LAPD's cold case files. There’s something deeply unsettling about seeing the high-resolution versions. You see the grass. You see the dirt under her fingernails. You see the sheer coldness of the act. It’s a reminder that beneath the "noir" aesthetic of 1940s Los Angeles, there was a very real, very violent underbelly.

Some researchers have used modern digital enhancement on the background of these photos. They look for cars in the distance or onlookers who might be the killer returning to the scene. It’s a common trope—killers love to watch the police work. But so far, no "smoking gun" has appeared in the grain of the film.

What we get wrong about Elizabeth Short

She wasn't a prostitute. This is a common lie that gets repeated. The 1947 LAPD, frustrated by their lack of progress, tried to smear her character. They wanted to make it seem like she "asked for it" by living a certain lifestyle. The truth is she was often homeless, hopping from one hotel to another, relying on the kindness of strangers. She was vulnerable.

💡 You might also like: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

When you look at a black dahlia murder picture, don't see a "case." See a person.

- She loved the movies.

- She had a fiancé who died in the war.

- She was struggling with a medical condition (infantilism) that made her private life much more complicated than the tabloids suggested.

The legacy of the Norton Avenue vacant lot

The lot isn't vacant anymore. It’s a residential neighborhood. People live there. They walk their dogs where Elizabeth Short’s body was found. There’s no plaque. There’s no memorial. There’s just the quiet of a suburban street that once held the most famous crime scene in American history.

The fascination persists because of the lack of closure. We hate an unfinished story. Every time a new "tell-all" book comes out claiming to solve the case, it’s just another layer of paint on a canvas that’s already too crowded. Whether it was George Hodel, a rogue doctor, or a nameless drifter, the answer is likely buried in a cemetery alongside the suspects.

Actionable insights for true crime researchers

If you are researching this case or looking for the black dahlia murder picture for historical purposes, keep these points in mind:

- Verify your sources. Many "crime scene" photos online are actually from movie sets (like the 2006 Josh Hartnett film). Real crime scene photos are always in black and white and usually have a specific "LAPD" watermark or evidence tag.

- Cross-reference the "missing" diary. Much has been made of Elizabeth’s missing address book. If you find "quotes" from it online, be skeptical. Most of the original pages were destroyed or lost by the Examiner reporters before the police could catalog them.

- Study the "Cleveland Torso Murders." Many experts, including FBI profilers, have looked for links between the Dahlia case and the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run. The MOs (method of operations) are eerily similar—bisected bodies and surgical precision.

- Visit the Los Angeles Police Museum. They occasionally have exhibits on the Black Dahlia. It’s the best place to see authentic evidence without the internet's filter of sensationalism.

The story of the Black Dahlia isn't just about a murder. It's about the birth of the modern media obsession with true crime. It's about how a single black dahlia murder picture can freeze a moment in time and turn a tragedy into a permanent mystery. Elizabeth Short deserved better than to be a "picture" on a screen, but eighty years later, that picture is all we have left of her.

To truly understand the case, you have to look past the gore. Look at the logistics. Look at the city of Los Angeles in 1947—a place of post-war boom, secret shadows, and a police department that was in over its head. The answer isn't in a grainy photo; it's in the gaps between the facts.

Next time you see that famous image, remember the girl from Medford who just wanted to be someone. She became the most famous woman in the world, just not for the reason she wanted.