You’ve probably heard people say that time heals all wounds. It’s a nice sentiment, honestly, but it’s biologically incomplete. When we talk about the biology of trauma, we aren't just talking about memories or "feeling sad" about something that happened five years ago. We are talking about a physical structural shift in how your brain processes reality. It’s a literal rewiring.

The body keeps a record.

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk basically turned the psychology world upside down with that concept, but the hard science behind it is even more fascinating—and a bit daunting. When you experience a terrifying event, your brain's "smoke detector" goes off. Usually, once the threat passes, the smoke detector turns off. But with trauma? The alarm gets stuck in the "on" position. You aren't just remembering the past; your body is convinced the past is still happening right now.

What's Actually Happening Inside Your Head?

The biology of trauma is mostly a story about three specific players: the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex.

Think of the amygdala as your internal security guard. It’s tiny, almond-shaped, and incredibly fast. Its only job is to spot danger. When you’re traumatized, the amygdala becomes hyper-responsive. It starts screaming "FIRE!" at things that aren't actually fire—like a car backfiring or a partner’s specific tone of voice.

Then you have the hippocampus. This is your librarian. It’s supposed to take your experiences, date-stamp them, and file them away in the "past" folder. But during a traumatic event, high levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) can actually suppress the hippocampus. The librarian trips and drops the books. Because the memory doesn't get a proper date-stamp, the brain treats the trauma as an evergreen, ongoing event.

This is why flashbacks feel so vivid. Your brain literally doesn't know it's 2026. It thinks it's still back in that room, or that car, or 그 relationship.

Then there’s the prefrontal cortex. That’s the "adult" in the room. It’s the part of the brain responsible for logic, planning, and impulse control. In a healthy brain, the prefrontal cortex can tell the amygdala, "Hey, calm down, it’s just a loud noise, we’re safe." But research shows that in people with PTSD or chronic developmental trauma, the connection between the logical brain and the emotional brain weakens. The "top-down" control fails. You can’t "think" your way out of a panic attack because the part of your brain that does the thinking has been sidelined by the part that does the surviving.

💡 You might also like: Mayo Clinic: What Most People Get Wrong About the Best Hospital in the World

The Vagus Nerve and the Body’s "Brake" System

It isn't just a brain thing.

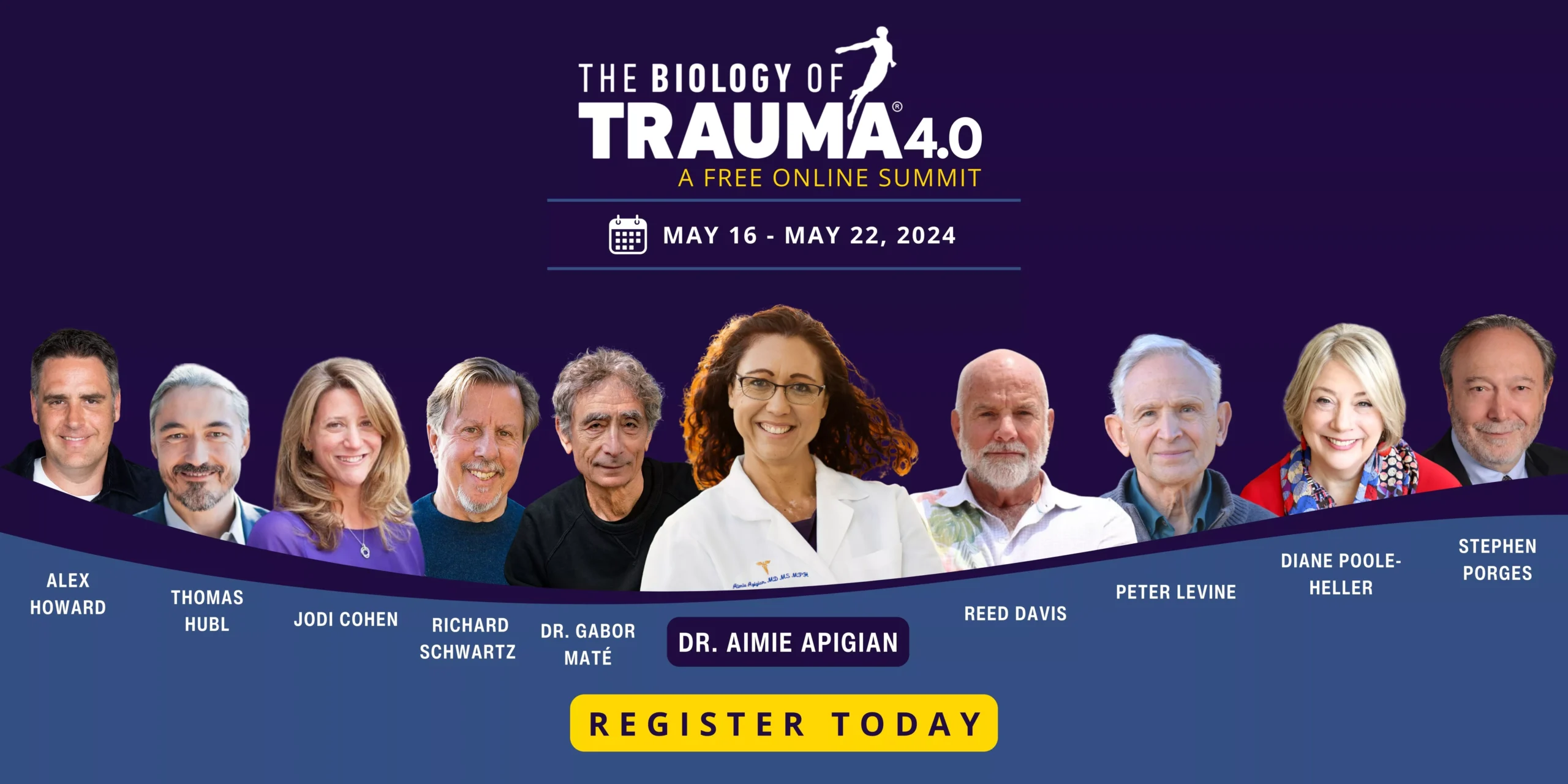

The biology of trauma lives in your chest, your gut, and your muscles. This is where the Vagus Nerve comes in. It's the longest cranial nerve in your body, acting like a superhighway between your brain and your vital organs. Dr. Stephen Porges developed something called Polyvagal Theory to explain this, and it’s a game-changer for understanding why people "freeze" instead of fighting back.

Most of us know about Fight or Flight. That’s the sympathetic nervous system kicking into high gear. Adrenaline spikes. Heart rate soars. You’re ready to move.

But there’s a third option: Dorsal Vagal Shutdown.

This is the "play dead" response. When a threat is too big to fight or run from, the body shuts down to preserve life. Heart rate drops. You might feel numb, cold, or disconnected from your body (dissociation). For many people, the biology of trauma means they get stuck in this "low power mode" long after the danger is gone. They feel lazy, unmotivated, or "foggy," but it’s actually their nervous system trying to protect them by staying invisible.

Why "Just Talking About It" Often Fails

Standard talk therapy is great for a lot of things. But if we’re looking at the biology of trauma, we have to admit its limitations. If the prefrontal cortex (the talking part) is offline, talking won't fix the problem. You can't talk a smoke detector into silence while it’s detecting smoke.

This is why "bottom-up" interventions are becoming the gold standard.

📖 Related: Jackson General Hospital of Jackson TN: The Truth About Navigating West Tennessee’s Medical Hub

Instead of starting with the mind, you start with the body. You’re trying to convince the nervous system it’s safe through physical signals. This is why things like EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) work for so many people. By using bilateral stimulation—moving your eyes back and forth—you’re helping the brain "reprocess" those date-stamps the hippocampus dropped earlier. It’s like finally filing those loose papers in the library.

Other methods include:

- Somatic Experiencing: Focusing on physical sensations to "discharge" stored tension.

- Neurofeedback: Training the brain to regulate its own electrical patterns.

- Yoga and Breathwork: Using the breath to manually override the Vagus Nerve and flip the switch from "danger" to "safe."

The Epigenetics of it All

Here is the really wild part: trauma might be in your DNA.

Not the sequence itself, but how the genes are expressed. A famous study by Rachel Yehuda at Mount Sinai looked at the children of Holocaust survivors. She found that these children had lower levels of cortisol—just like their parents—which made them more vulnerable to stress. They hadn't experienced the trauma themselves, but their biology was "pre-set" to a higher state of alert.

It’s called epigenetic inheritance. Your ancestors' survival strategies can become your biological baseline. It’s not a "defect." It’s your body trying to prepare you for a world it thinks is dangerous. Understanding this helps remove a lot of the shame. You aren't "broken"; you’re a finely-tuned survival machine that’s reacting to data it inherited.

Neuroplasticity: The Good News

If the brain can be rewired by trauma, it can be rewired by healing. This is neuroplasticity. The brain is plastic. It’s not a stone carving.

We used to think the brain was "set" by age 25. We were wrong. You can grow new neural pathways at 40, 60, or 80. Every time you practice a grounding technique, or successfully navigate a trigger without spiraling, you are physically strengthening the bridge between your prefrontal cortex and your amygdala. You are building a more resilient librarian.

👉 See also: Images of the Mitochondria: Why Most Diagrams are Kinda Wrong

It takes time. It’s messy. But the biology of trauma isn't a life sentence. It’s just the current state of your hardware.

How to Actually Start Healing the Nervous System

Since this is a biological issue, you need biological solutions. You can't just read your way out of this; you have to do things.

1. Track your "Window of Tolerance"

Start noticing when you are "hyper-aroused" (anxious, angry, racing heart) versus "hypo-aroused" (numb, tired, spaced out). Most people with trauma spend very little time in the middle. Simply naming the state—"I am currently in dorsal vagal shutdown"—can sometimes help the prefrontal cortex come back online.

2. Use Temperature Shocks

If you’re stuck in a flashback or a high-anxiety spike, splash ice-cold water on your face or hold an ice cube. This triggers the Mammalian Dive Reflex, which forces your heart rate to slow down immediately. It’s a biological "reset" button.

3. Prioritize Proprioception

Trauma often makes you feel "floaty" or disconnected from your limbs. Heavy blankets, weighted vests, or even just pushing your hands hard against a wall can provide the sensory input your brain needs to realize where your body ends and the world begins.

4. Find a Trauma-Informed Practitioner

Look for therapists who specifically mention "Somatic," "Polyvagal," or "EMDR." If a therapist only wants to talk about your childhood without ever addressing how your heart is racing in the chair, they might not understand the full biology of what you're dealing with.

5. Movement is Non-Negotiable

Because trauma is stored in the motor system (the "fight" or "flight"), you have to move to get it out. This doesn't mean a marathon. It means shaking your arms when you feel tense, dancing, or walking. Stagnancy tells the brain you are still "frozen." Movement tells the brain the "danger" phase of the event is over.