It was 1943. London was exhausted. You’ve probably heard stories about the Blitz, the stoicism, and the "Keep Calm and Carry On" attitude that supposedly defined the era. But there’s a darker, claustrophobic side to that history that doesn't always make it into the highlight reels. The Bethnal Green tube station disaster isn't a story of enemy bombers or direct hits. It is a story of panic, a single tripped foot, and a massive government cover-up that lasted for years.

Honestly, it’s one of the most heartbreaking events in British history. 173 people died. They weren't killed by the Luftwaffe. They were killed by the weight of each other.

On the night of March 3, 1943, the air raid sirens wailed across East London at about 8:17 PM. By this point in the war, people knew the drill. They headed for the deep shelters. The Bethnal Green station was a prime choice because it was one of the few spots on the Central Line that had been completed but wasn't yet being used for trains. It was a cavernous, safe space. Or at least, it was supposed to be.

Why the Bethnal Green tube station disaster was so uniquely horrific

Most people assume a bomb hit the station. It didn't. That’s the most common misconception you'll run into. About ten minutes after the sirens started, a relatively new anti-aircraft battery in nearby Victoria Park fired off a massive volley of rockets.

It was a new sound. It wasn't the usual thud of the guns people were used to. It was a terrifying, screeching roar.

In the pitch black of the blackout, the crowd at the top of the stairs thought the worst had happened. They thought the neighborhood was being leveled. People surged forward, desperate to get down those steps. Then, a woman carrying a baby slipped. Some accounts, like those from survivor Joan Martin, suggest she simply lost her footing on the wet, narrow stairs.

She fell. A man tumbled over her. Within seconds, a human logjam formed.

📖 Related: Trump New Gun Laws: What Most People Get Wrong

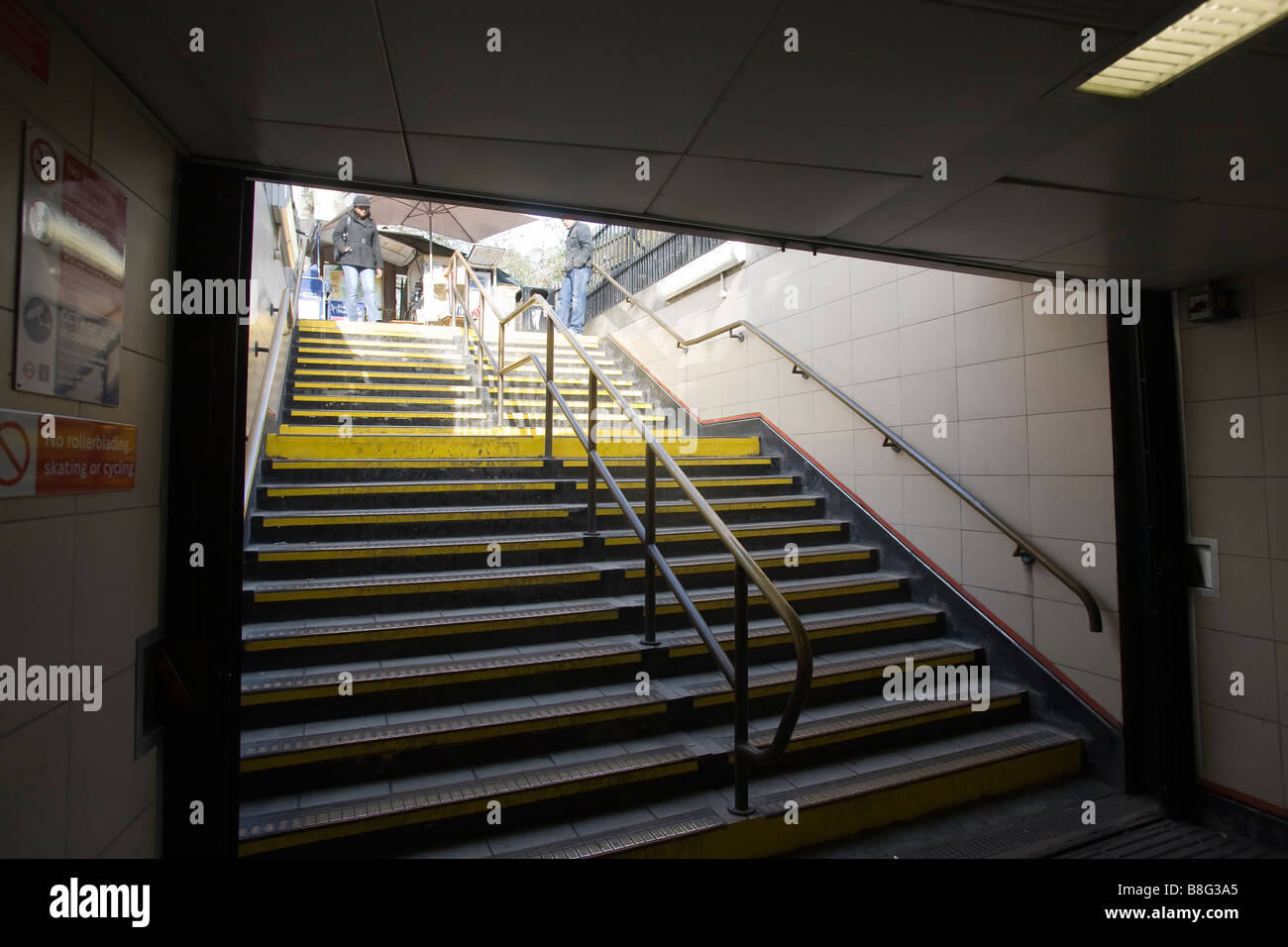

But the people at the top of the stairs couldn't see what was happening below. They kept pushing. They were terrified. The entrance was a narrow, 15-foot wide staircase with no central handrail. Think about that for a second. No handrail in a pitch-black tunnel during a mass panic. It was a recipe for a catastrophe.

The pressure became immense. We're talking about a "compression asphyxia" event. People weren't trampled in the way we usually think—they were squeezed so tightly they literally couldn't breathe. It took nearly three hours to pull everyone out. When the rescuers finally reached the bottom, they found a literal wall of bodies, tangled and silent.

The demographics of the tragedy

The numbers are staggering and deeply personal for East Enders. Out of the 173 who died, 62 were children.

- 27 men

- 84 women

- 62 children

It’s a lopsided statistic that shows who was heading for the shelters: mothers, the elderly, and kids while the younger men were away at the front. The youngest victim was only five months old.

The cover-up and the fight for the truth

The government’s immediate reaction was, frankly, shameful. They didn't want the news getting out. They were worried it would destroy morale or, worse, give the Germans a psychological win. They basically told the survivors to shut up.

Sir John Anderson, the Home Secretary at the time, actually suppressed the initial report by Eric Thompson. Why? Because the report highlighted that the local council had warned the government years earlier that the entrance was dangerous. The Bethnal Green Borough Council had requested permission to install a central handrail and fix the stairs back in 1941. The government had denied the request, claiming it was a waste of money and materials.

👉 See also: Why Every Tornado Warning MN Now Live Alert Demands Your Immediate Attention

They blamed the victims instead.

They leaked stories suggesting the crowd had panicked for no reason, or that "aliens" (immigrants and Jewish residents) had caused the rush. It was a classic move: deflect blame from the bureaucrats and put it on the people who suffered. It wasn't until after the war ended that the full scale of the negligence was acknowledged.

Even then, the official secrets act kept a lid on a lot of the specifics for decades.

Acknowledging the long-term trauma

For the survivors, the Bethnal Green tube station disaster never really ended. For years, the East End remained quiet about it. You’d walk past the station, and you just didn't talk about it. It was a collective trauma.

Dr. Ian Duncan, a historian who has studied the London home front, points out that this event caused more civilian deaths than many actual bombing raids. Yet, because there was no "enemy" to hate, the grief became internal. People blamed themselves. They wondered if they had pushed too hard. They wondered if they could have pulled that woman up.

Lessons we still haven't fully learned

You look at modern stadium disasters—Hillsborough is the big one that comes to mind—and you see the same patterns. Poor crowd control, lack of physical barriers, and an immediate rush by the authorities to blame the "mob" rather than the infrastructure.

✨ Don't miss: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

The Bethnal Green tragedy proves that panic isn't some irrational madness that hits "other" people. It’s a logical response to a perceived threat when you are trapped in a space that isn't designed for your safety.

What to do if you're visiting today

If you go to Bethnal Green today, you'll see a beautiful, haunting memorial called "Stairway to Heaven." It’s an inverted wooden staircase suspended in the air, with 173 small holes cut into the roof to let light through—one for every soul lost.

- Location: It's right in Bethnal Green Gardens, literally steps away from the station entrance where it happened.

- The Stairs: You can still see the original entrance. It’s been modified, of course, but the tight quarters are still evident.

- The Museum: The nearby Young V&A (formerly the Museum of Childhood) sometimes holds local history exhibits that touch on the wartime experience of the East End.

Actionable insights for history buffs and researchers

If you're looking to dig deeper into the Bethnal Green tube station disaster, don't just stick to the Wikipedia summary. The nuance is in the primary sources.

- Check the National Archives: Look for the suppressed 1943 reports. Seeing the handwritten notes from officials trying to "manage" the news is eye-opening.

- Read "The 173": There are several local history books that list the victims by name. Reading those names makes the event much more real than just seeing a triple-digit number.

- Visit the Memorial at Night: The way the light interacts with the "Stairway to Heaven" monument is designed to be experienced in person. It’s a powerful lesson in how we remember—and how we forget—public tragedies.

- Research the "Stairway to Heaven" Trust: This charity was responsible for getting the memorial built when the government wouldn't. It’s a great example of community-led justice.

The most important thing you can take away from this is a sense of skepticism toward "official" narratives during times of crisis. The people of Bethnal Green weren't a "panicky mob." They were tired, scared civilians who were let down by the very people tasked with keeping them safe.

We owe it to those 173 people to remember that their deaths weren't an accident of fate—they were a failure of planning. When you walk down the steps into a London Underground station today, and you see the handrails, the clear signage, and the staff managing the flow, remember that those features were paid for in blood at Bethnal Green.

Keep this history in mind next time you're in a crowd. Space and exits matter. Infrastructure isn't just about convenience; it's about survival.

Next Steps for Further Research:

- Locate the Stairway to Heaven Memorial in Bethnal Green Gardens to see the names of the victims.

- Search the Imperial War Museum online archives for oral histories from East End survivors of the 1943 crush.

- Investigate the Bethnal Green Borough Council's letters from 1941 to understand the specific safety warnings that were ignored by the Home Office.