Before they were the Mop Tops, before the suits, and long before the world went mad for them, there was Hamburg. It was greasy. It was loud. Honestly, it was kind of a mess. But in 1961, a group of scruffy Liverpool kids backed a singer named Tony Sheridan at the Top Ten Club on the Reeperbahn. This wasn't just another gig. It resulted in the first professional recordings of The Beatles with Tony Sheridan, a collection of tracks that serve as the "Year Zero" for modern pop music.

Most people think Love Me Do was the beginning. It wasn't.

If you want to understand how a bar band turned into a global phenomenon, you have to look at these German sessions. They weren't even called The Beatles on the record sleeve; they were "The Beat Brothers" because the German label, Polydor, thought "Beatles" sounded a bit too much like the German word Peedles, which is slang for... well, something you wouldn't want to name a band after.

The Hamburg Pressure Cooker

The Beatles were exhausted. They were playing eight hours a night, fueled by cheap beer and "prellies" (Preludin, a stimulant popular in the clubs). Tony Sheridan was the star. He was a British guitarist who had already found some fame in West Germany, and he was good. Really good. Paul McCartney later admitted that they all looked up to Sheridan. He had the look, the swagger, and the Gibson ES-175 that they all envied.

Bert Kaempfert, a German producer who later became famous for "Strangers in the Night," saw them performing. He didn't necessarily see the magic in John, Paul, George, and Pete Best yet, but he saw a tight backing unit for his main man, Sheridan.

In June 1961, they went into a school assembly hall—the Friedrich-Ebert-Halle—to record. It wasn't a high-tech studio. It was a stage with some curtains and a few microphones. They recorded several tracks, the most famous being "My Bonnie."

Why the Tony Sheridan Sessions Sound So Different

When you listen to The Beatles with Tony Sheridan, the first thing that hits you is the raw, unpolished energy. It’s essentially a rock and roll time capsule. This wasn't the polished George Martin sound of 1963. This was the sound of a band that had been playing in smoky basements for months.

The Lead Vocals: Sheridan handles almost all of them. He has a rough, Elvis-inspired delivery. John Lennon only gets a look-in on "Ain't She Sweet," and you can hear the snarl in his voice that would later define "Twist and Shout."

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The Lead Guitar: George Harrison was only 18. On "Cry for a Shadow," an instrumental he co-wrote with John Lennon, you can hear him imitating the Shadows’ style, but with a bit more grit. It’s actually the only track ever credited to Lennon-Harrison alone.

The Drumming: This is Pete Best, not Ringo Starr. Pete's style was the "Atom Beat"—a heavy, relentless thud. While it worked for the clubs, it’s one of the reasons George Martin eventually wanted a session drummer, leading to Pete's sacking.

The Bass: Paul McCartney isn't on his famous Hofner violin bass yet. He was playing a Framus guitar converted into a bass because Stuart Sutcliffe had recently left the band. It’s clunky, but it drives the song.

Basically, it's the sound of a band learning how to be a band.

The "My Bonnie" Legend

There’s a bit of a myth that a kid named Raymond Jones walked into Brian Epstein’s record shop in Liverpool and asked for "My Bonnie" by The Beatles with Tony Sheridan, and that’s how Brian discovered them. Whether Raymond Jones actually existed or if Brian just noticed the buzz in the Mersey Beat newspaper is debated by historians like Mark Lewisohn. But the fact remains: this German record is what put them on Brian Epstein’s radar.

Without the Tony Sheridan sessions, Brian might never have gone to the Cavern Club. No Brian, no EMI contract. No EMI contract, no Beatlemania. It’s a massive "what if" in music history.

Honestly, the recordings themselves are a bit of a mixed bag. "My Bonnie" starts with a slow, almost painful intro before kicking into a standard rocker. "The Saints" (When the Saints Go Marching In) is a bit corny. But then you have "Why," a ballad where Sheridan really shines, and the boys provide some surprisingly tight backing vocals. You can hear the beginnings of those famous harmonies that would later change the world.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

The Complicated Discography

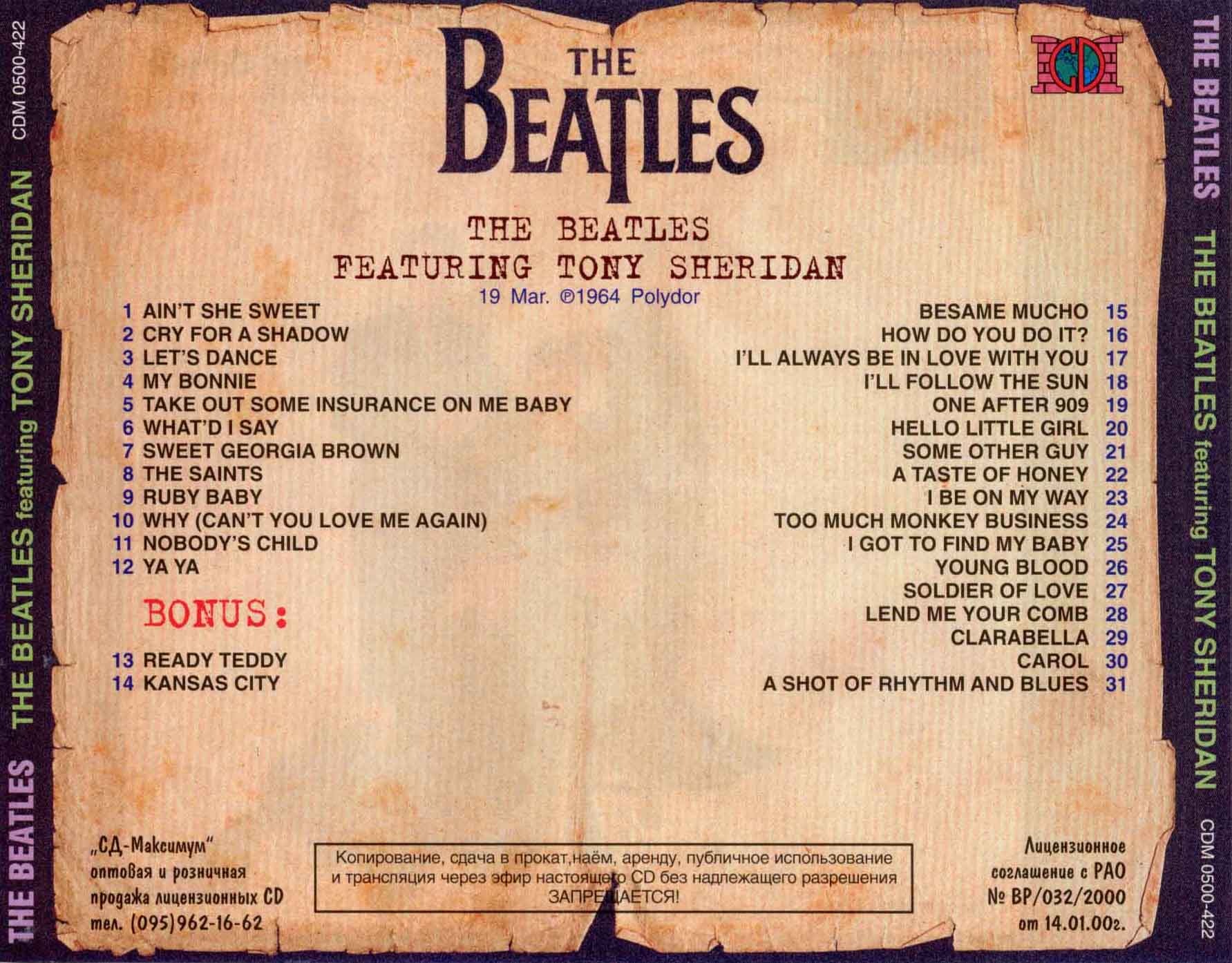

Tracking down these recordings today is a nightmare for collectors. Because Polydor owned the tapes, they milked them for everything they were worth once the Beatles became famous. They’ve been repackaged a thousand times under names like The Beatles' First, In the Beginning, and The Early Tapes.

You've probably seen these albums in bargain bins. The covers usually feature a photo of the "Mop Top" era Beatles, which is totally misleading. At the time of these recordings, they still had their hair slicked back in greasy pompadours. They looked like rockers, not pop stars.

It’s also worth noting that Sheridan kept recording as The Beat Brothers with other musicians. So, if you buy a "Beat Brothers" record, you might not even be hearing John, Paul, George, and Pete. You have to check the session dates. The core tracks featuring the actual Beatles were recorded in June 1961 and a few more in May 1962 (like "Sweet Georgia Brown").

Technical Specs of the Session

For the gear nerds out there, these sessions were remarkably simple.

- Microphones: Mostly Neumann U47s.

- Tape Machine: A portable two-track Telefunken.

- Guitars: Sheridan used his Gibson, Harrison used his Gretsch Duo Jet, and Lennon used his Rickenbacker 325.

- The Vibe: Complete chaos. They were recording in a school hall during the day while kids were likely in classes nearby.

The producer, Bert Kaempfert, reportedly told them to "play more simply." He didn't want the fancy fills or the wild energy. He wanted a steady beat for the German youth to dance to. You can almost hear the band straining against those leash-lines, trying to break out.

Why Does This Still Matter?

We live in an era where every demo and rehearsal is leaked online instantly. In 1961, getting into a room with a professional microphone was a huge deal. For The Beatles with Tony Sheridan, this was their first taste of the "real" music business. It taught them how to behave in a studio, the importance of timing, and—crucially—that they didn't want to be anyone's backing band.

Sheridan remained a fixture in the Hamburg scene until he passed away in 2013. He was always gracious about his "famous" backing band, though he jokingly called himself "the fifth Beatle" (like about twenty other people did).

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

If you're a casual fan, you might find these tracks a bit jarring. They don't have the sheen of Sgt. Pepper. But if you're a student of rock history, they are essential. It’s the sound of the engine turning over for the first time. It’s loud, it’s a bit smoky, and it’s undeniably human.

Sorting Fact From Fiction

There are a few things people get wrong about this era. First, the Beatles weren't "discovered" in the studio. They were hired help. They were paid about 300 Deutsche Marks each for the session. At the time, that was a decent chunk of change for a few days' work.

Second, the relationship wasn't purely professional. They genuinely liked Sheridan. He taught George Harrison a lot about lead guitar playing. He showed them how to command a stage. When you listen to the banter between tracks on some of the bootlegs, you can hear the camaraderie.

However, by 1962, when they recorded "Sweet Georgia Brown," the dynamic had changed. The Beatles were starting to get famous in their own right. They weren't just the backing band anymore; they were a local sensation. Shortly after that final session, they met George Martin and the rest is, quite literally, history.

How to Listen to These Tracks Properly

Don't just stream them on a crappy speaker. To really "get" the Tony Sheridan sessions, you need to find a version that hasn't been over-processed. Many modern "remasters" try to clean up the hiss and end up killing the room's natural reverb.

- Find a copy of The Beatles' First (the 1964 Polydor release).

- Listen for Pete Best's kick drum—it's the heartbeat of the Hamburg sound.

- Pay attention to the background vocals on "My Bonnie." That’s the sound of 1961 Liverpool.

- Check out "Ain't She Sweet." It’s the closest you’ll get to hearing what they sounded like at the Cavern Club before they were stars.

These recordings are the link between the 1950s rock and roll of Little Richard and Gene Vincent and the 1960s British Invasion. They are the bridge. Without Tony Sheridan, that bridge might have taken a lot longer to build.

Moving Beyond the Records

If you want to dive deeper into this specific period, your next steps shouldn't just be listening to the music. You need the context of what Hamburg was actually like in the early sixties.

- Read "Tune In" by Mark Lewisohn: This is the definitive biography. The section on the Hamburg sessions is incredibly detailed, covering everything from the food they ate to the exact microphones used.

- Watch "Backbeat": While it takes some creative liberties with the story of Stuart Sutcliffe, it captures the vibe of the Hamburg clubs and the Sheridan era perfectly.

- Visit the Indra and Kaiserkeller: If you ever find yourself in Hamburg, these clubs (or the sites where they stood) still exist. Standing in those spaces makes the music make sense. It’s loud, cramped, and intense.

The story of the Beatles with Tony Sheridan is a reminder that even the greatest legends started out as someone else’s supporting act. It’s a messy, loud, and fascinating piece of the puzzle that remains essential for anyone who wants to understand how four guys from Liverpool changed the world.