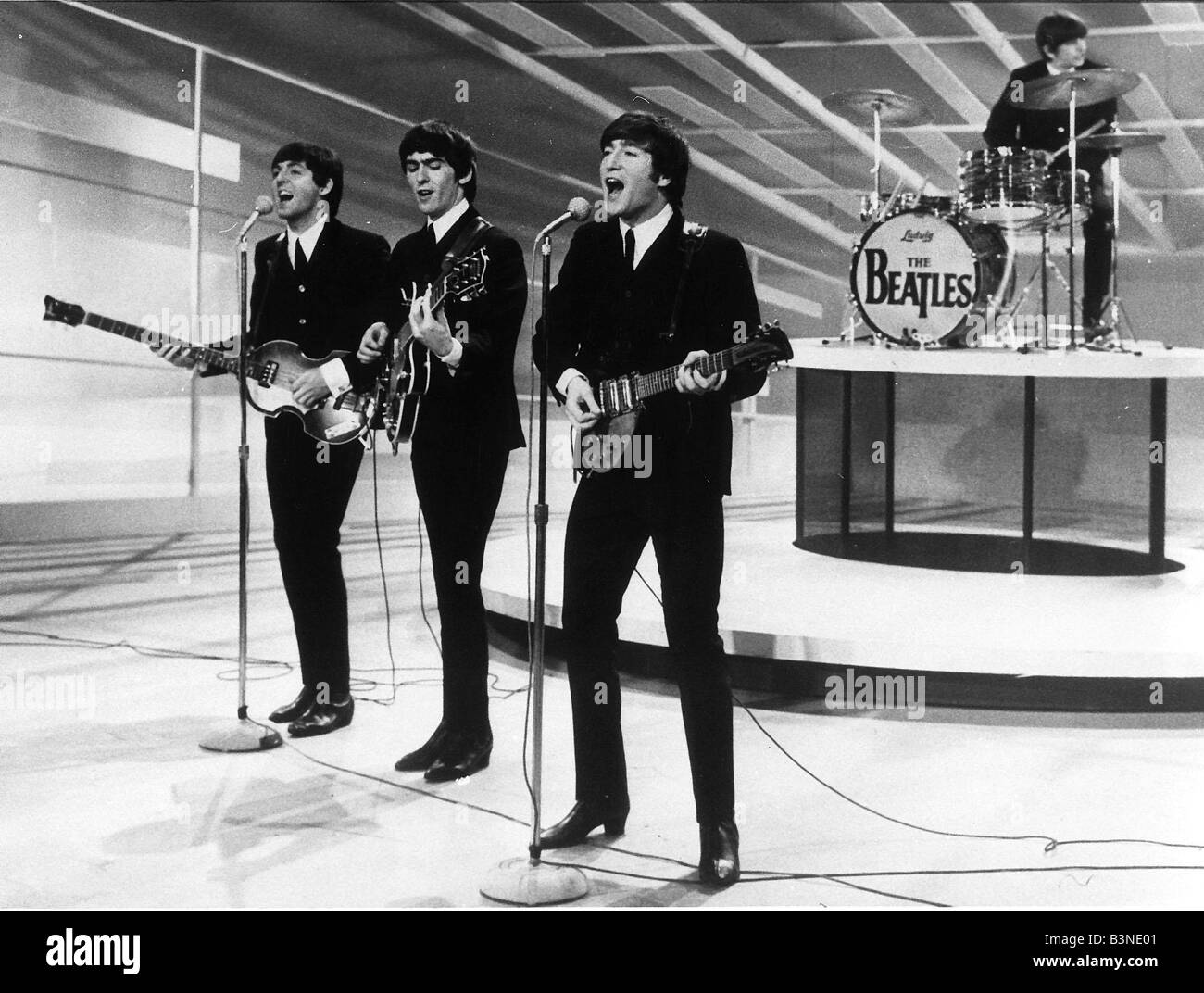

It is a common misconception that the Fab Four just stopped touring because they got lazy or wanted to hide in the studio with weird instruments. Honestly? The Beatles on stage became a literal safety hazard. By 1966, the situation wasn't just loud; it was borderline parasitic. John, Paul, George, and Ringo were essentially trapped in a bubble of high-frequency screaming that rendered their actual musical output secondary to the spectacle of their presence.

If you look at the footage from Shea Stadium in 1965, you see four guys trying to play rock and roll through what were basically public address systems meant for announcing baseball lineups. Vox had to custom-build 100-watt amplifiers—the AC100—specifically so the band could have a prayer of hearing themselves. It didn't work. Ringo famously said he had to watch the sway of his bandmates' backsides just to keep time because he couldn't hear the backbeat.

The Acoustic Chaos of 1963 to 1966

Early on, the energy was infectious. In the Cavern Club or the Star-Club in Hamburg, the Beatles on stage were a tight, leather-clad (then suit-clad) machine. They played eight-hour sets. You don't do that without becoming a singular unit. But once the "Beatlemania" switch flipped, the stage became a cage.

Think about the technical limitations. They didn't have monitors. Today, a garage band has better foldback speakers than the most famous group in history had at the height of their fame. They were flying blind. George Harrison later lamented that the band’s musicianship actually suffered. Why practice a complex harmony if 50,000 people are going to drown it out with a wall of noise that tops 120 decibels? That is louder than a jet taking off.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The Gear That Struggled to Keep Up

- The Vox AC100: This was the "Super de Luxe" amp. It was huge. It was heavy. It still lost the war against the fans.

- The Ludwig Black Oyster Pearl Kit: Ringo’s setup was modest, but he hit those drums like they owed him money just to pierce through the din.

- Hofner 500/1: Paul’s "violin" bass became an icon, but its hollow body often fought feedback in these massive, non-acoustic environments.

The sheer physicality of these shows was grueling. They weren't playing for two hours like Taylor Swift does today. They played 25 to 30 minutes. They'd sprint on, blast through twelve songs at breakneck speed, and sprint off before the barricades collapsed. It was a heist, not a recital.

When the Circus Turned Sour

By the time they hit the road for their final tour in 1966, the vibe had shifted from joyful to terrifying. The "more popular than Jesus" comment from Lennon had sparked protests. In the American South, the Beatles on stage were now targets. They were performed under the threat of snipers and firecrackers that sounded like gunshots.

During the 1966 performance at the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo, the atmosphere was strangely different. The Japanese police enforced a strict "no-screaming" policy. For the first time in years, the band could actually hear how out of tune they were. It was a wake-up call. They realized they had become a parody of themselves. The nuances of Revolver, which they were recording at the time, were impossible to recreate live anyway. How do you play "Tomorrow Never Knows" with two guitars and a drum kit? You don't.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

The Candlestick Park Finale

August 29, 1966. San Francisco.

The setlist was short. They opened with "Rock and Roll Music" and ended with "Long Tall Sally."

They knew it was over.

John and Paul took a camera on stage to take pictures of themselves. They were documenting the end of their lives as "The Lads."

The industry didn't understand it. Promoters thought they were crazy to walk away from that kind of money. But for the band, the stage had become a place where they couldn't be musicians. They were just objects. It's a miracle they lasted as long as they did before retreating to the sanctuary of Abbey Road.

The Rooftop Concert: One Last Blast

We can't talk about the Beatles on stage without the 1969 rooftop performance at Apple Corps. This was the antithesis of the stadium years. No screaming fans. No 100-watt Vox amps struggling for air. Just the four of them (plus Billy Preston) on a cold London roof.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

It proved they could still play. Despite the years of isolation, the chemistry was instantaneous. When you watch the Get Back documentary, you see the tension melt the second they plug in. That is the true legacy of their live career. They were a pub band that got too big for the world, but at their core, they were just four guys who knew exactly where the "one" was.

Why It Still Matters

Modern touring is a choreographed, digital masterpiece. The Beatles on stage were the opposite. It was raw, dangerous, and technically flawed. But that's why we still watch the grainy footage. You’re seeing the birth of the modern concert industry—the moment people realized that music could be a mass-communal experience, even if nobody could hear a single note.

Actionable Insights for Beatles Enthusiasts:

- Listen to the Hollywood Bowl recordings: If you want to hear what they actually sounded like through the screaming, the 1977 (and remastered 2016) Live at the Hollywood Bowl album is the best document of their live power.

- Study the Budokan '66 footage: Watch the Tokyo shows to see the band realize they need to get back to the studio. Their faces tell the whole story.

- Analyze the "Get Back" Rooftop Set: Pay attention to the interaction between Ringo and Paul. It's a masterclass in rhythm section telepathy.

To truly understand the Beatles, you have to acknowledge the sacrifice of their live years. They gave up their ability to hear themselves so the world could hear something new. It was a chaotic, sweaty, and often frightening chapter, but it's what forged the greatest studio band of all time.