Everything we think we know about how it finished is usually a bit off. We like a clean narrative. We want a villain—usually Yoko or Paul’s ego—but the reality of the Beatles in the end was way more like a messy, long-distance breakup where nobody wants to be the first to move their stuff out of the apartment.

They were tired.

By 1969, these four guys had been living in a pressurized cabin of global fame for nearly a decade. Imagine being twenty-something and having every single sneeze analyzed by the press while you're also trying to reinvent modern music. It’s exhausting just thinking about it. They weren't just a band; they were a multi-million dollar corporation called Apple Corps that was hemorrhaging money and patience. When people search for what happened to the Beatles in the end, they often expect a single moment of explosion. It wasn't that. It was a series of small, painful fractures that finally turned into a canyon.

The Get Back Disaster and the Roof

The January 1969 sessions—what we now know as Let It Be—were basically a nightmare. They tried to go "back to basics." No overdubbing. No studio magic. Just four guys in a room.

It backfired.

🔗 Read more: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Twickenham Film Studios was cold, cavernous, and had terrible acoustics. George Harrison actually quit the band for five days during these sessions. He was done with being treated like a junior partner by Paul McCartney and John Lennon. He went home, wrote "Wah-Wah," and realized he didn't need the headache anymore. He only came back because they promised to move the sessions to their own Apple Studio and scrap the idea of a live TV special.

That famous rooftop concert on January 30, 1969, wasn't some triumphant return. It was a compromise. It was the only way they could think of to finish the film they were shooting. If you watch the footage closely, you see the spark is still there when they play, but the second the music stops, the air leaves the room.

Allen Klein and the Great Divide

If there is a "point of no return" for the Beatles in the end, it’s probably the meeting where they had to pick a manager. This is where the business side poisoned the art. John, George, and Ringo wanted Allen Klein, a tough-talking accountant from New York who had repped the Rolling Stones. Paul wanted Lee Eastman—his new father-in-law.

You can see the problem.

💡 You might also like: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

McCartney felt ganged up on. The other three felt Paul was trying to control them through his family. It wasn't about the music anymore; it was about contracts, percentages, and who got to sign the checks. When John Lennon sat the group down in September 1969 and told them, "I want a divorce," the world didn't know yet. They kept it a secret for months because of business negotiations. They were legally a band but emotionally strangers.

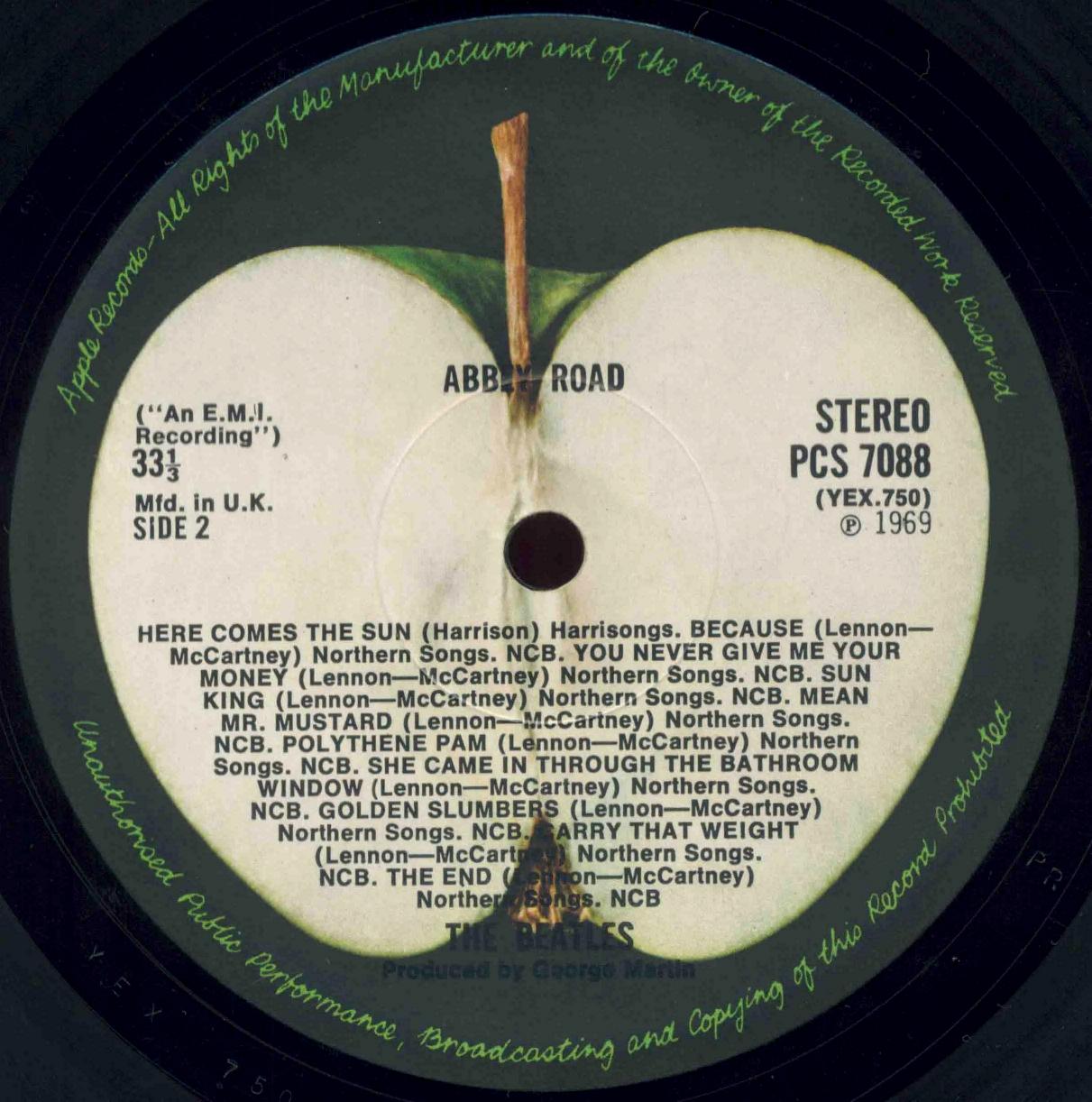

Abbey Road: The Final Miracle

It's honestly a miracle that Abbey Road exists. After the misery of the Let It Be sessions, they decided to make one last record "the way they used to." George Martin, their legendary producer, only agreed to come back if they let him actually produce.

This resulted in some of their best work, but the tension was still thick. During the recording of "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," the other three grew to hate the song because Paul made them do dozens of takes. John Lennon famously hated it, calling it "more of Paul's granny music."

Yet, when you listen to the "Medley" on side two, you hear a band that still functioned as a single organism. The tragedy of the Beatles in the end is that they were still the best in the world at what they did, even while they couldn't stand being in the same hallway together.

📖 Related: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Why It Still Hurts

People still debate this because it feels unfinished. We have this idea that if they just had a vacation, or if Brian Epstein hadn't died in '67, they’d still be together in the 70s. But look at the solo careers. John wanted to do primal scream therapy and political activism. George wanted to explore spirituality and slide guitar. Paul wanted to make melodic pop-rock and tour. Ringo just wanted to play drums and be happy. They had outgrown the "mop-top" suit.

The Legal Aftermath

When Paul McCartney finally announced he was leaving the band in April 1970 via a press release for his solo album, the other three were furious. Not because he left—they all knew it was over—but because he "stole" the announcement to promote his own project.

The legal battles that followed lasted years. Because they were tied together in a partnership, Paul had to sue the other three members in the High Court to dissolve the band. It was ugly. It involved affidavits where they insulted each other's work. It was the furthest thing from "All You Need Is Love" imaginable.

What We Can Learn From the End

Looking back at the Beatles in the end, the takeaway isn't that they failed. It's that they survived as long as they did. Most bands don't last eight years, let alone change the world in that time. They showed that creative partnerships have a natural lifespan.

If you're looking to dive deeper into this specific era, there are a few things you should do to get the full picture beyond the myths:

- Watch Peter Jackson's "Get Back" documentary. It’s eight hours long, but it’s the only way to see the actual dynamics. You’ll see that they didn't hate each other 24/7; they were mostly just bored and frustrated.

- Listen to "New Morning" by Bob Dylan and "All Things Must Pass" by George Harrison. These albums, released right around the breakup, show where the musical "vibe" was shifting—away from the polished studio sound of the 60s and into something more raw.

- Read "You Never Give Me Your Money" by Peter Doggett. This is hands-down the best book on the financial and legal nightmare of the breakup. It moves past the "who wrote what" and explains why they ended up in court.

- Compare the "Let It Be" album with "Let It Be... Naked." The latter removes the Phil Spector "Wall of Sound" orchestration. It gives you a much clearer idea of what the band actually sounded like in the room during their final days.

The end of the Beatles wasn't a failure of talent. It was just the inevitable result of four geniuses growing up and realizing they didn't fit in the same box anymore. It’s a messy, human story, and that’s probably why we’re still talking about it sixty years later.