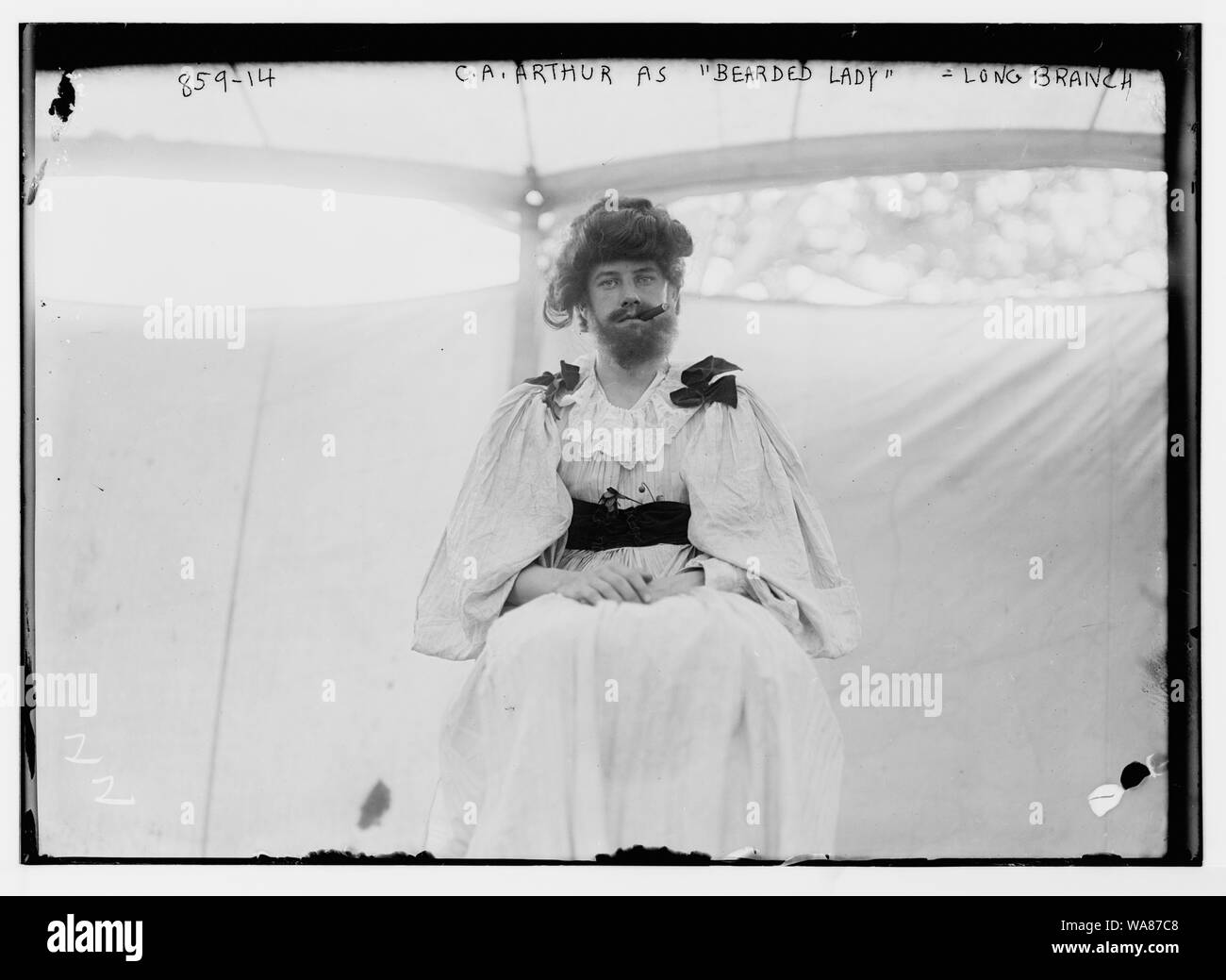

Walk into any vintage-themed bar or browse a collection of Victorian photography, and you'll eventually run into her. The image is unmistakable. A woman, often dressed in the finest silk or velvet of the 19th century, staring back at the camera with a gaze that feels both defiant and incredibly weary. But it’s the facial hair that stops people. Usually, it’s a full, lush beard that would make a modern lumberjack jealous.

The bearded lady at the circus isn't just a leftover trope from a "Greatest Showman" fever dream. She was real.

For a long time, these women were some of the highest-paid performers in the world. They weren't just "freaks" tucked away in a dark tent; many were international celebrities who commanded massive salaries, navigated complex marriages, and negotiated their own contracts. Honestly, it’s kind of wild when you think about it. At a time when most women couldn't even vote, women like Annie Jones or Josephine Clofullia were traveling the globe and out-earning most men.

More Than a Gimmick: The Reality of Hypertrichosis and PCOS

People usually want to know the "why" behind the beard. Was it fake? Usually, no. While there were definitely "fakes" in the lower-tier traveling carnivals—men in dresses or women with spirit gum and yak hair—the big names at P.T. Barnum’s or Ringling Bros. were the real deal.

✨ Don't miss: The Burgess Meredith Penguin: Why This Batman TV Show Performance Still Rules Gotham

Medical science back then was, well, pretty rudimentary. They called it "lusus naturae"—a sport of nature. Today, we have names for these conditions. Most of these women likely had polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which affects about 1 in 10 women today and can cause hirsutism (excessive hair growth). Others had hypertrichosis, a rare genetic condition often nicknamed "Ambras syndrome" that causes hair to grow all over the body.

Think about Julia Pastrana. She was a Mexican performer in the 1850s who was often cruelly marketed as a "Bear Woman." She had terminal hair growth and gingival hyperplasia, which thickened her lips and gums. It wasn't just a costume she could take off at night. This was her biology.

The tragedy here is that for many of these women, their bodies were seen as public property. Doctors would perform "examinations" to prove they were actually female, and these results were often published in newspapers to drum up ticket sales. It was a bizarre mix of medical voyeurism and high-stakes marketing.

Annie Jones and the Golden Age of the American Circus

If you’re talking about the bearded lady at the circus, you have to talk about Annie Jones. She’s basically the GOAT of this niche world. Born in Virginia in 1865, she started her "career" at only nine months old.

P.T. Barnum paid her parents a weekly salary of $150. In the 1860s, that was a small fortune.

Jones wasn't just a spectacle; she was a refined woman. She was a talented musician and spoke with a level of grace that intentionally contrasted with her appearance. That was the "hook." The circus owners wanted to create a juxtaposition: the "savage" beard against the "civilized" Victorian lady. She spent 36 years traveling with the circus. She became a spokesperson for "The Freaks," famously campaigning to have the word removed from the industry’s vocabulary. She wanted them to be called "prodigies" or "attractions."

She was also married twice. Her life was a constant cycle of performance, travel, and the weird reality of being a household name whom people paid a nickel to stare at.

The Performance of Gender

What’s fascinating is how these women leaned into femininity. To make the beard "pop," they didn't dress like men. They wore corsets, lace, jewelry, and elaborate updos. They were hyper-feminine.

This was a calculated move.

If they looked like men, the act failed. There’s no "shock" in a bearded man. The profit was in the blur. The audience was forced to confront something that didn't fit into their neat little boxes of "male" and "female." This tension made the bearded lady at the circus a permanent fixture of the sideshow for over a century.

- Josephine Clofullia: She gained fame in the 1850s and famously had her beard measured by a court to prove she wasn't a man in disguise during a fraud trial. She even modeled her beard after Napoleon III, who supposedly gave her a diamond.

- Clementine Delait: A French cafe owner who refused to join the circus full-time because she preferred running her business. She sold postcards of herself to customers and became a local legend.

- Jane Barnell: Known as "Lady Olga," she appeared in the 1932 cult classic film Freaks. She hated how the movie portrayed her peers, but she was a staple of the Hubert’s Museum in Times Square for years.

The Dark Side of the "Attraction"

We shouldn't romanticize this too much. While some women found financial freedom, others were exploited. Julia Pastrana’s story is particularly haunting. When she died in childbirth in 1860, her manager—who was also her husband—had her body and the body of her infant son mummified. He then continued to tour with their remains for years, charging people to see them.

It took until 2013 for her body to finally be returned to Mexico for a proper burial.

👉 See also: Who Sings the Song Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Real Story Behind the Covers

That’s the grim reality of the sideshow era. The line between "performer" and "property" was paper-thin. When you see a vintage poster for a bearded lady at the circus, you’re looking at a person who had to commodify their medical condition just to survive in a world that didn't have a place for them in "polite" society.

Why Do We Still Care?

The sideshow as we knew it died out by the mid-20th century. Television and movies killed the "live" curiosity, and the medicalization of "abnormalities" made people feel guilty about staring.

But the bearded lady never really left.

Look at Harnaam Kaur, a modern British model and activist with a full beard due to PCOS. She’s used the visual language of the old circus performers but flipped the script. She’s not an "attraction"; she’s an influencer. The fascination remains because we are still obsessed with the boundaries of the human body. We still want to see what happens when the rules of "normal" are broken.

The circus provided a safe space for that curiosity. It was a place where the weird was celebrated—even if that celebration was rooted in a bit of exploitation.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you want to look deeper into the history of the bearded lady at the circus, you shouldn't just look at old posters. You have to look at the primary sources to get the real story.

✨ Don't miss: Dandadan is Basically Chaos and That is Why You Need to Watch It

- Check the Census Records: Many circus performers used stage names. If you’re researching someone like Annie Jones, look for "professional performers" in the census records of Bridgeport, Connecticut (Barnum's winter quarters).

- Analyze the Photography: Study the "Cabinet Cards" of the 1800s. These were the trading cards of the era. Notice the background—they are always in high-end studios, never in the dirt. This tells you about their status.

- Read the Memoirs: Some performers, like Percilla "The Monkey Girl" Lauther, gave interviews later in life that provide a much different perspective than the "official" circus programs.

- Visit Real Archives: The Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin, and the Shelburne Museum in Vermont hold actual artifacts, costumes, and contracts that show the business side of being a "wonder."

The legacy of the bearded lady at the circus is one of resilience. These women took a condition that could have kept them hidden in a back room and used it to see the world. They were businesswomen, performers, and rebels. While the "freak show" is gone, the conversation they started about beauty and bodies is still happening today.

To understand the history of the circus is to understand the history of how we treat people who are different. It’s messy, it’s uncomfortable, and it’s deeply human.