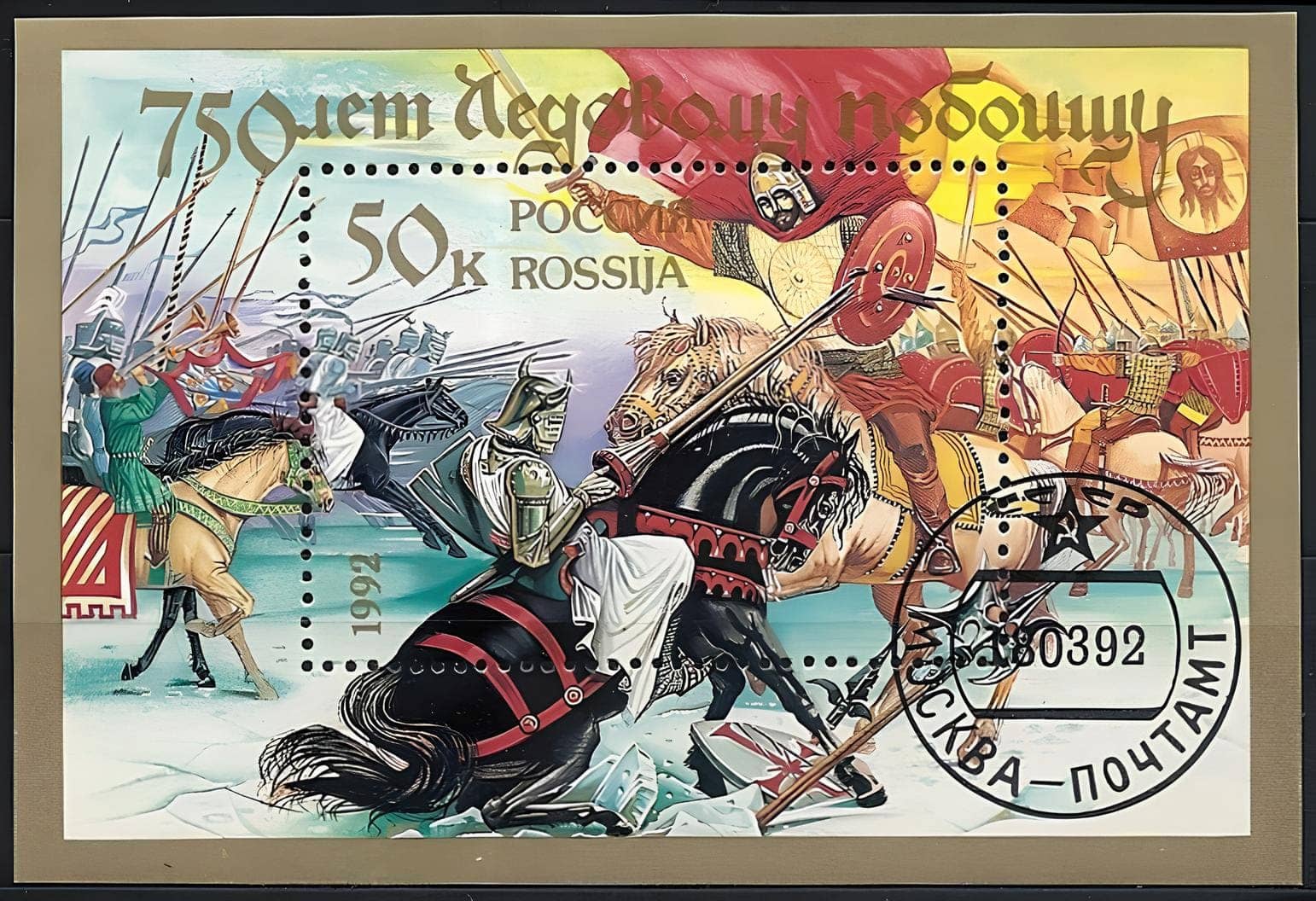

History isn't a movie. We’ve all seen the dramatic cinematic shots—heavily armored knights crashing through thin ice while a heroic Prince Alexander Nevsky looks on. It’s a great visual. Honestly, it’s one of the most iconic images in Russian history. But if you actually look at the primary sources from 1242, the reality of the Battle on the ice is a lot messier, a lot more tactical, and way more interesting than the "ice breaking" myth suggests.

You’ve probably heard the standard version. On April 5, 1242, the Teutonic Knights tried to invade Russia, got lured onto a frozen lake, and drowned because their armor was too heavy. It’s a clean story. It’s also mostly a 20th-century invention popularized by Sergei Eisenstein’s 1938 film. If you’re looking for the truth about what happened on Lake Peipus, you have to dig through the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle and the Novgorod First Chronicle. These texts don't focus on drowning knights. They focus on a brutal, grinding melee that changed the map of Eastern Europe forever.

Why the Battle on the Ice actually happened

This wasn't just a random border skirmish. It was part of the Northern Crusades. The Livonian Order—basically a branch of the Teutonic Knights—wanted to expand their influence and, more importantly, bring Roman Catholicism to the Orthodox lands of Pskov and Novgorod. They had already taken Pskov. Novgorod was next.

Alexander Nevsky wasn't some grizzled old veteran at the time. He was in his early twenties. Imagine that. You're 22 years old, and you're responsible for stopping a professional machine of German crusaders and Danish vassals. Nevsky had already beaten the Swedes at the Neva River in 1240 (hence the name "Nevsky"), but the Teutonic Order was a different beast. They were disciplined. They used the "pig" formation—a massive, iron-clad wedge designed to punch through enemy lines like a hot knife through butter.

The "Pig" vs. The Militia

When the two armies met on the morning of April 5, the weather was bitingly cold. The location was specifically the narrow strait connecting the northern and southern parts of Lake Peipus (also known as Lake Chudskoe).

🔗 Read more: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Nevsky knew he couldn't beat the knights in a head-on cavalry charge on open ground. So, he chose the lake. Why? Not necessarily to drown them. He chose it because the flat, frozen surface neutralized the knights' ability to use terrain for flanking. He forced them into a frontal assault.

The Teutonic "wedge" struck the Russian center. It worked, initially. The knights smashed into the Novgorod militia—mostly infantrymen who weren't professional soldiers. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle admits the knights were "making their way through the troops," but then they got bogged down. This is the part people miss. The Russian flanks, comprised of professional horsemen and archers, swung inward.

The wedge became a trap.

What about the ice breaking?

Let's address the elephant in the room. Did the ice break? Probably not in the way you think. Contemporary accounts like the Novgorod First Chronicle mention the battle was fought "on the ice," and they describe the grass being stained with blood. Wait, grass? That implies they were near the shore, possibly on a frozen marsh or very shallow water.

💡 You might also like: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

Archaeological expeditions led by the Soviet Academy of Sciences in the 1960s (the expedition of Georgiy Karaev) spent years trying to find the exact spot. They found plenty of evidence of the geological shifts in the lake, but very little in the way of "sunken treasure" or mass graves of armored men at the bottom. Most historians today believe that while some knights might have fallen through during the retreat—spring ice is notoriously unstable—it wasn't the primary cause of death. The knights died because they were surrounded and hacked to pieces by Russian axes and spears.

Numbers, Propaganda, and Reality

If you read the Russian chronicles, they claim they killed thousands of Germans. If you read the German accounts, they say only 20 knights died and six were captured.

The truth?

It’s in the middle. The "20 knights" figure likely refers only to the full Brothers of the Order—the elite noblemen. It doesn't count the thousands of Estonian foot soldiers and lower-ranking mercenaries who made up the bulk of the Crusader army. Total casualties were likely in the range of several hundred to a few thousand, which, for the 13th century, was an absolute bloodbath.

📖 Related: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

The geopolitical fallout

This battle stopped the eastward expansion of the Crusader orders for centuries. It established a hard border between the Western Latin world and the Eastern Orthodox world. Nevsky became a saint, not just because he was a good fighter, but because he was a shrewd diplomat. He realized that the real threat wasn't the knights—it was the Mongols. By securing his western flank at the Battle on the ice, he was able to pay tribute to the Golden Horde and keep the Russian identity alive under Mongol suzerainty.

The Legacy of Lake Peipus

Today, the battle is a cornerstone of Russian national identity. It was used as a rallying cry during World War II when Stalin commissioned the Eisenstein film to warn the Nazis about what happens to Germans who invade.

But if we strip away the propaganda, we see a masterclass in tactical positioning. Nevsky used the environment. He understood his enemy’s psychology. He knew that the knights’ greatest strength—their heavy, unstoppable momentum—could be turned into their greatest weakness if they were forced to fight in a confined, slippery space where they couldn't maneuver.

Lessons for History Buffs and Travelers

If you’re planning to visit the area, it’s a quiet, beautiful region today. The border between Estonia and Russia runs right through the middle of the lake.

- Visit Pskov: This is where the campaign started and ended. The Pskov Krom (Kremlin) is one of the most imposing medieval fortresses in Russia.

- The Monument on Mount Sokolikha: Outside Pskov, there’s a massive bronze monument to Nevsky and his druzhina (bodyguards). It captures the scale of the legend.

- Check the Ice: If you're there in winter, the lake still freezes solid. You can walk out and realize how terrifying it would be to stand there in 50 pounds of mail while a "pig" of cavalry charges at you.

Actionable Insights for Researching Medieval Battles

To truly understand events like the Battle on the ice, you have to look past the "top-down" history taught in schools.

- Cross-reference your sources. Always look at what the "losing" side said. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle is fascinating because it’s a rare look at the Crusader perspective, showing they actually respected the Russian archers' skill.

- Understand the Logistics. Armor didn't make people sink like stones instantly, but fighting in it for four hours is an Olympic-level feat of endurance. Exhaustion killed more people in 1242 than thin ice did.

- Evaluate the "Great Man" Theory. While Nevsky was a brilliant strategist, the victory belonged to the common infantry of Novgorod who stood their ground against a terrifying cavalry charge. Without the militia's discipline in the center, the flank maneuver would have never worked.

History is almost never as simple as the movies make it out to be. The Battle on the ice wasn't won by a geological fluke; it was won by a young commander who knew his terrain and a group of soldiers who refused to break under the pressure of the most feared heavy cavalry in Europe.