October 1776 was a mess. George Washington was basically running for his life across New York, trying to keep the Continental Army from evaporating into thin air. If you look at the map of the Battle of White Plains, it doesn't look like a classic victory. Honestly, it wasn't. It was a gritty, desperate scramble that arguably saved the American Revolution from ending before it really began.

Most people think of the Revolution as a series of heroic stands. This wasn't that. It was a strategic retreat disguised as a confrontation.

After losing Long Island and being kicked out of Manhattan, Washington’s troops were tired, hungry, and—frankly—terrified of the British regulars. General William Howe was moving slow, though. That’s the detail that always bugs historians. Why didn't he just crush them? By the time the British reached White Plains on October 28, Washington had managed to dig in on the high ground. But "dug in" is a generous term for a bunch of farmers with rusty muskets and dwindling gunpowder.

The Chaos on Chatterton Hill

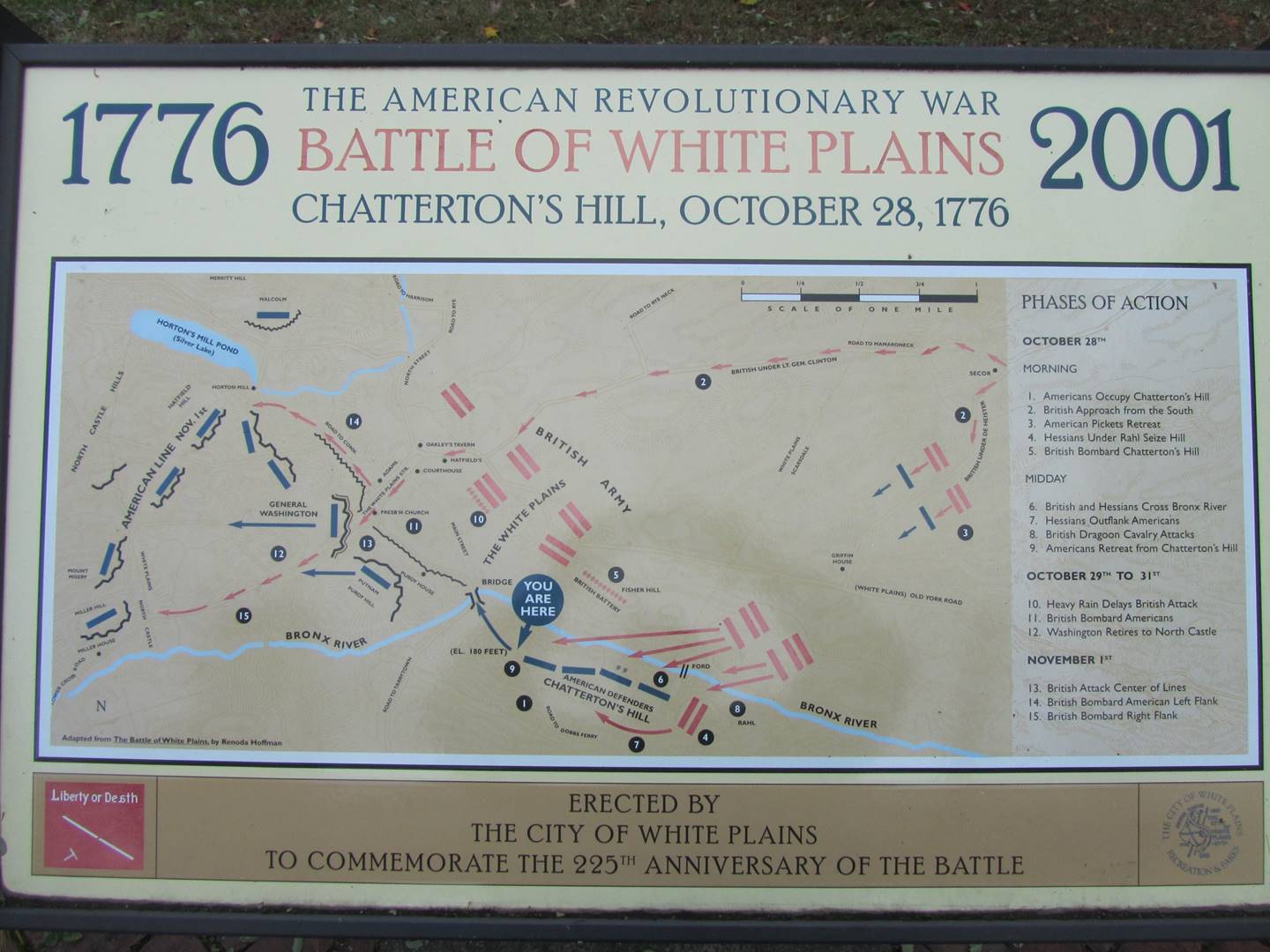

The real heart of the Battle of White Plains happened on a steep piece of land called Chatterton Hill. This was the American right flank. Washington sent Alexander McDougall to hold it with about 1,600 men. They were supported by some Alexander Hamilton-led artillery—yes, that Hamilton—who actually did some decent damage before things went sideways.

Then came the Hessians.

If you were a colonial soldier in 1776, the sight of Hessian mercenaries was a nightmare. They were professional killers. They didn't just march; they moved like a machine. About 4,000 British and Hessian troops started crossing the Bronx River. The water wasn't deep, but the banks were slippery, and the American militia started taking potshots at them from the woods.

🔗 Read more: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

It was loud. It was smoky. And for a second, it looked like the Americans might hold.

But then the British cavalry showed up. You have to realize that most American soldiers had never seen a coordinated cavalry charge. The sheer noise of galloping hooves and the sight of flashing sabers caused the militia to break. The Spencer’s 2nd Connecticut Regiment and some of the Maryland troops fought hard, but the "raw" militia units basically turned tail. It was a rout, but a slow one.

Why Howe Didn't Finish the Job

This is the part that drives people crazy. Howe took the hill. He had the momentum. The Americans were retreating to even higher ground at North Castle.

Instead of pursuing them and ending the war right there, Howe just... stopped.

He waited for reinforcements. He worried about the weather. He spent the next couple of days shuffling his troops around while a massive rainstorm turned the battlefield into a swamp. By the time he was ready to move again on October 31, Washington had slipped away. Again. Washington was becoming a master of the "tactical disappearance."

💡 You might also like: Typhoon Tip and the Largest Hurricane on Record: Why Size Actually Matters

Historians like David McCullough have pointed out that Howe’s cautious nature was Washington’s greatest asset. If Howe had been a more aggressive commander, the Battle of White Plains wouldn't be a footnote; it would be the final chapter of the United States.

The Logistics of a Losing Win

We talk about generals and flags, but the Battle of White Plains was really about shoes and flour. The Continental Army was falling apart.

- Soldiers were wrapping their feet in rags because their boots had disintegrated.

- Dysentery was ripping through the camps.

- The "commissary" was basically non-existent.

When you look at the casualty counts, the numbers seem small by modern standards. The Americans lost maybe 150 to 200 men (killed or wounded). The British and Hessians lost around 230. In terms of a 18th-century battle, those are "moderate" losses. But for Washington, every veteran lost was a disaster. He couldn't replace trained men. Howe, on the other hand, had the entire British Empire backing him up, yet he was the one acting like he was afraid to lose a single company.

It’s also worth noting the terrain. White Plains wasn't just a random spot. It was a choke point. By holding that position, Washington prevented Howe from getting behind him and cutting off the escape route to the Hudson Highlands.

Misconceptions About the Battle

You'll often hear that White Plains was a "draw." That's a bit of a stretch. The British took the field. They took the hill. They forced the Americans to retreat. In any traditional sense, that's a British victory.

📖 Related: Melissa Calhoun Satellite High Teacher Dismissal: What Really Happened

But in the context of the Revolutionary War, a "victory" for the British only counted if it destroyed Washington's army. Since the army survived to fight another day (and eventually win at Trenton a few months later), White Plains is often reframed as a strategic success for the Americans.

Another weird myth? The "Headless Horseman." Washington Irving’s famous story is set in nearby Sleepy Hollow, and the legend says the ghost was a Hessian trooper who had his head carried away by a cannonball during the Battle of White Plains. It's a cool bit of folklore that actually has a grain of truth—artillery fire was indeed intense during the struggle for Chatterton Hill, and many soldiers were buried in unmarked graves across the county.

The Aftermath and the Move to New Jersey

After Howe realized Washington wasn't going to come down and fight a "gentlemanly" battle on the flats, he turned his attention south. He went after Fort Washington and Fort Lee. Those were genuine disasters for the Americans. Thousands of men were captured, and the retreat through New Jersey began.

White Plains was the last time the two main armies would face off in New York for a long time. It marked the end of the "New York Campaign," a period where Washington learned the hard way that he couldn't beat the British in a head-to-head, conventional fight. He had to be faster. He had to be sneakier. He had to be willing to lose the ground to save the cause.

Practical Insights for History Buffs

If you’re planning to visit the site today, don't expect a pristine battlefield like Gettysburg. It’s a city now. But there are still ways to see what happened.

- Visit the Purdy House: This served as Washington's headquarters. It's one of the few standing structures that actually witnessed the events.

- Chatterton Hill (Battle Hill): There’s a small park and a monument. Stand at the top and look down toward the Bronx River. Even with the modern buildings, you can see why holding that high ground was so vital. The slope is steep. Imagine climbing that in wool gear while people are firing muskets at you.

- The Miller House: Located in North White Plains, this was another headquarters used by Washington. It’s been restored and gives a much better sense of the domestic side of the war.

The Battle of White Plains teaches us that "winning" isn't always about holding the field. Sometimes, winning is just about surviving long enough to wait for your opponent to make a mistake. Washington played the long game. He knew that as long as his army existed, the Revolution existed. He left the hills of Westchester battered and bruised, but he left with his army intact. That made all the difference.

To really understand this period, look into the specific movements of the Maryland 400 or the diaries of soldiers like Joseph Plumb Martin. Their firsthand accounts of the hunger and the confusion at White Plains strip away the romanticism and show the raw reality of 1776. Examine the topographical maps of Westchester County from that era; you'll see exactly how the ridges and swamps dictated every move Washington made. Keep exploring the primary sources at the National Archives to see the actual correspondence between Washington and the Continental Congress during those frantic October days.