It was freezing. Not just "chilly Tennessee winter" freezing, but the kind of damp, bone-deep cold that makes a musket barrel feel like a rod of ice. On the night of December 31, 1862, two massive armies were huddled in the cedar brakes near Murfreesboro, so close they could hear each other’s brass bands. Legend says the bands started a duel—the Federals played "Yankee Doodle," the Confederals snapped back with "Dixie." Then, in a moment that feels too Hollywood to be real but actually happened, both sides joined in for a rendition of "Home, Sweet Home."

A few hours later, they started killing each other.

The Battle of Stones River (or Murfreesboro, if you’re asking the South) was a clumsy, desperate, and incredibly violent affair. It wasn't the tactical masterpiece of Gettysburg or the sweeping drama of Antietam. It was a slugfest. By the time it was over, the casualty percentage was higher than almost any other major engagement in the American Civil War. Abraham Lincoln later told Union General William Rosecrans that if the North had lost there, "the nation could scarcely have lived over."

That’s not hyperbole.

The High Stakes of a Murfreesboro Winter

By late 1862, the Union was hurting. Badly. Burnside had just embarrassed the North at Fredericksburg. The Emancipation Proclamation was set to go into effect on January 1, 1863, and Lincoln desperately needed a victory to prove he wasn't just shouting into the wind. If the Army of the Cumberland failed in Tennessee, the political pressure to sue for peace might have become unbearable.

Braxton Bragg, the Confederate commander, was sitting in Murfreesboro. He was a prickly, widely disliked man, but he knew his geography. He was protecting the gateway to Chattanooga. If the Union took Chattanooga, they owned the railroads. If they owned the railroads, the Deep South was wide open.

Rosecrans—"Old Rosy" to his men—marched out of Nashville on December 26. He had about 41,000 men. Bragg had around 35,000. On paper, the Union had the edge. On the ground? The ground was a nightmare of limestone outcroppings and "cedar brakes" so thick you couldn't see five feet in front of your face.

The Morning the Union Almost Vanished

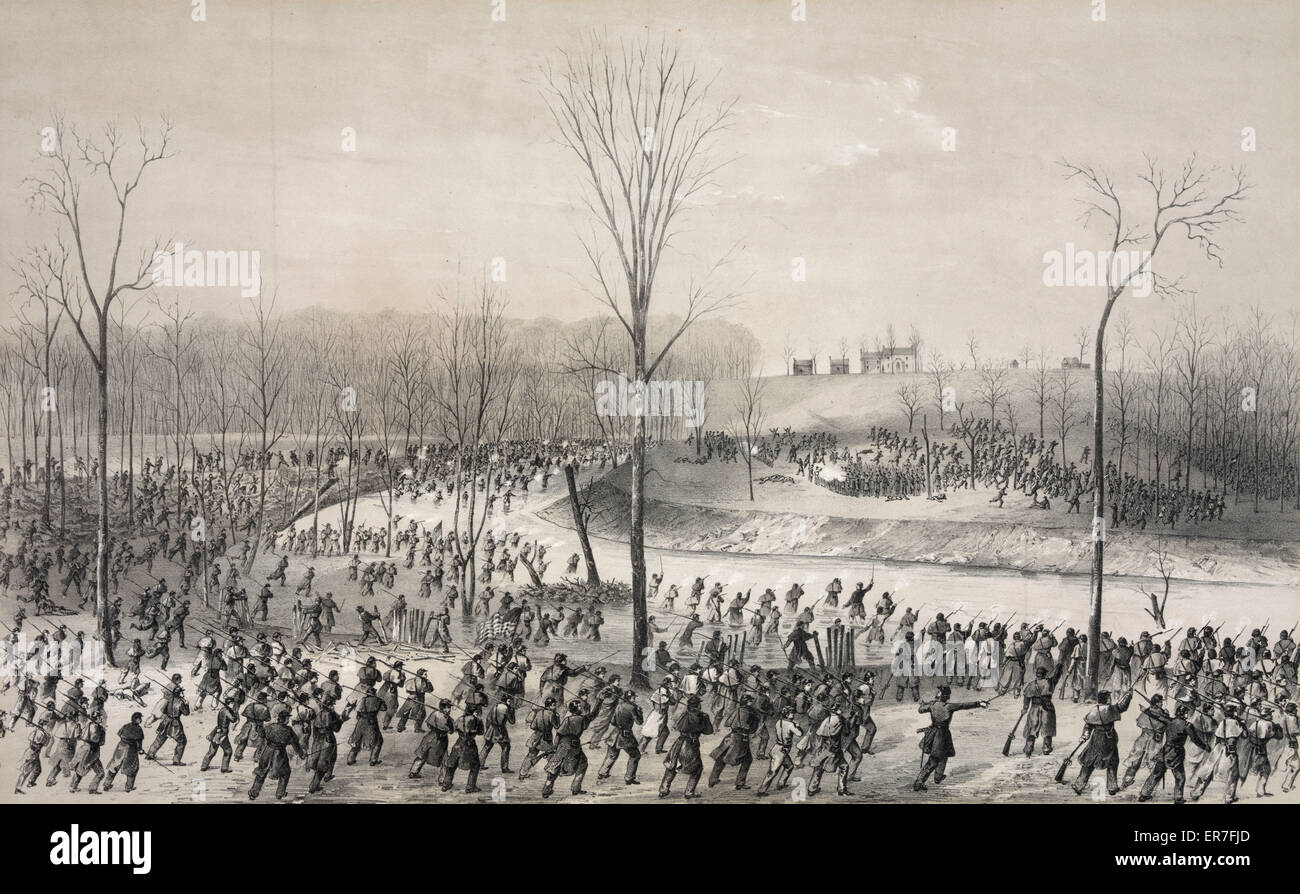

Bragg struck first. At dawn on December 31, while Union soldiers were still boiling coffee, the Confederate left wing under William Hardee smashed into the Union right. It was a total surprise. The Union line didn't just bend; it folded back like a pocketknife.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

Men were running through the woods in their long johns. It was chaos.

General Philip Sheridan, however, was one of the few who had his men ready. He’d sensed something was wrong and had his division under arms before the sun came up. Sheridan’s stand in the "cedar brakes" bought Rosecrans the one thing he desperately needed: time.

Without Sheridan’s stubbornness, the Battle of Stones River would have ended by noon with a Union rout. Instead, Rosecrans was able to pull his troops back to the Nashville Pike, forming a tight "V" shape with his back to the river. He was literally fighting with his back against the wall.

The Slaughter Pen and the Round Forest

There's a spot on the battlefield known as the "Slaughter Pen." The name tells you everything you need to know. The limestone rocks there acted like natural trenches, but they also trapped men in crossfires. The fighting was so intense that the 18th Ohio Infantry reported losing nearly half their men in a matter of minutes.

Then there was the "Round Forest." The Union held a small patch of woods that sat right on the railroad line. Bragg sent wave after wave of Mississippians and Texans at it. It became the anchor of the Union line. The soldiers started calling it "Hell's Half Acre."

General Rosecrans was everywhere. He was covered in the blood of his chief of staff, Julius Garesché, who was decapitated by a cannonball while riding right next to him. Rosecrans didn't flinch. He just kept riding, rallying the men, screaming that they would die right there before they retreated. It was gritty. It was ugly. Honestly, it was the kind of leadership the Union had been missing.

Why Didn't They Just Leave?

By the night of the 31st, both armies were exhausted. Most commanders would have retreated. Rosecrans called a council of war in a log cabin. Some of his generals wanted to pull back to Nashville. Rosecrans looked at them and basically said, "We’re staying."

🔗 Read more: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

New Year’s Day was weirdly quiet. Both sides just sat there, bleeding and shivering. Bragg was convinced Rosecrans would retreat. He even sent a telegram to Richmond claiming a great victory.

He was wrong.

Breckinridge’s Suicide Charge

On January 2, Bragg lost his patience. He ordered John C. Breckinridge (a former Vice President of the United States turned Confederate General) to attack a Union position on a hill across the river.

Breckinridge knew it was a suicide mission. He allegedly cried out, "My poor orphans!" as he led his Kentucky troops forward—this is why they became known as the Orphan Brigade.

The Confederates charged across an open field. Rosecrans had massed 58 cannons on the heights across the river. When the Confederates got close, the Union artillery opened up. It wasn't a fight; it was a massacre. In about 45 minutes, nearly 1,800 Confederates fell. The river literally ran red.

That was the breaking point. Bragg realized Rosecrans wasn't budging, and he didn't have the strength left to force him. The Confederates slipped away into the night toward Tullahoma.

The Brutal Math of the Aftermath

When the smoke cleared, the numbers were staggering.

💡 You might also like: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

- Union Casualties: 12,906

- Confederate Casualties: 11,739

Out of roughly 76,000 men engaged, nearly 25,000 were killed, wounded, or missing. That is a casualty rate of about 33%. To put that in perspective, Gettysburg had a casualty rate of about 27%. The Battle of Stones River was, proportionally, a much deadlier day at the office.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often call this a "draw." Technically, on the field, it kind of was. Bragg wasn't destroyed, and Rosecrans didn't capture Murfreesboro because he was a tactical genius—he got it because Bragg walked away.

But strategically? It was a massive Union win.

- Foreign Recognition: Britain and France were watching. If the Union had lost Stones River right after Fredericksburg, they might have officially recognized the Confederacy.

- The Emancipation Proclamation: Because Rosecrans held the field, the Proclamation took effect on January 1st with the weight of a winning army behind it.

- The Road to Atlanta: This battle secured Middle Tennessee. It provided the base of operations Rosecrans would use for the Tullahoma Campaign later in 1863, which was one of the most brilliant (and bloodless) maneuvers of the war.

Why Stones River Matters in 2026

We tend to focus on the "big" names—Lee, Grant, Jackson. But Stones River was a "soldiers' battle." It was won by the grit of Midwestern farmers and the stubbornness of a General who refused to admit he was beaten.

It also changed how the North viewed the war. It wasn't going to be a quick adventure. It was going to be a long, grinding war of attrition. The cemetery at Stones River today is one of the oldest national cemeteries in the country, and walking through those rows of headstones—many marked "Unknown"—is a sobering reminder of the cost of that transition.

How to Truly Understand the Battle

If you want to grasp what happened here, don't just read a textbook. Look at the terrain. The "karst" topography (that jagged limestone) dictated the entire fight. It forced men into pockets. It broke up formations. It turned an organized battle into a series of disconnected, terrifying skirmishes in the dark woods.

Historians like Peter Cozzens (who wrote No Better Place to Die) argue that Stones River was the true turning point in the West, even more so than Vicksburg. If Rosecrans loses here, the Union loses the heart of the country.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you’re planning to visit or study the Battle of Stones River, don't just stay in the car.

- Walk the McFadden Farm Loop: This is where the 58 guns massed. When you stand where those cannons were and look across the river, you realize the Confederates never had a chance. The elevation advantage is terrifying.

- Find the Hazen Brigade Monument: This is the oldest intact Civil War monument in the United States, built by the soldiers themselves in 1863. It’s located in the Round Forest. The fact that they built it while the war was still happening tells you how much they knew this spot mattered.

- Study the "Cedar Brakes": If you go to the park, walk into the thickets. You'll see how impossible it was to maintain a "line." It explains why the Union right wing collapsed so fast—they couldn't see the Rebels until they were twenty yards away.

- Check the Primary Sources: Read the "Official Records" (the ORs) for the 18th Ohio or the 1st Louisiana. The language they use isn't poetic; it's visceral. They talk about the sound of bullets hitting trees like "hail on a tin roof."

- Look Beyond the Field: Visit the Oaklands Mansion in Murfreesboro. It served as a headquarters and shows the civilian side of the occupation. It contextualizes why the town was such a strategic prize for both sides.