History is usually written by the winners. In the case of the Battle of Mons Graupius, it was written by the winner's son-in-law.

That’s basically the first thing you need to know if you want to understand what happened in the Scottish Highlands in AD 83 or 84. We’re relying almost entirely on Publius Cornelius Tacitus. He was a brilliant writer, sure, but he was also the ultimate hype-man for his father-in-law, Gnaeus Julius Agricola. Agricola was the Roman governor of Britain, and he really wanted to prove he’d finally conquered the "wild" north.

It was a bloodbath. Or so we’re told.

Tacitus describes a massive clash where 30,000 Caledonian warriors faced off against the Roman war machine. On paper, it’s the climax of the Roman conquest of Britain. It's the moment the empire supposedly broke the back of Scottish resistance once and for all. But there’s a massive problem that has been driving archaeologists crazy for centuries: we can't find the battlefield.

Where on Earth was the Battle of Mons Graupius?

Imagine a battle with over 40,000 people hacking at each other. You'd expect to find something, right? A stray gladius, a rusted shield boss, or at least a few pits full of bones.

Nothing. Not a single confirmed physical trace of the Battle of Mons Graupius exists in the Scottish landscape.

Because of this, historians are split into two camps. Some think we just haven't looked in the right spot yet. Others think Tacitus might have been... let's say "generous" with the truth to make Agricola look like a legend.

Most researchers point toward the northeast. Bennachie in Aberdeenshire is a popular candidate because it fits the description of a "lofty hill." Others argue for the Gask Ridge or even as far north as Sutherland. If you look at the Roman ramparts at Cawdor or the massive camp at Muiryfold, you can see the Romans were definitely up there. They were building high-capacity camps that could hold tens of thousands of men. They were ready for a fight.

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

The numbers don't always add up

Tacitus claims the Romans didn't lose a single legionary. Not one.

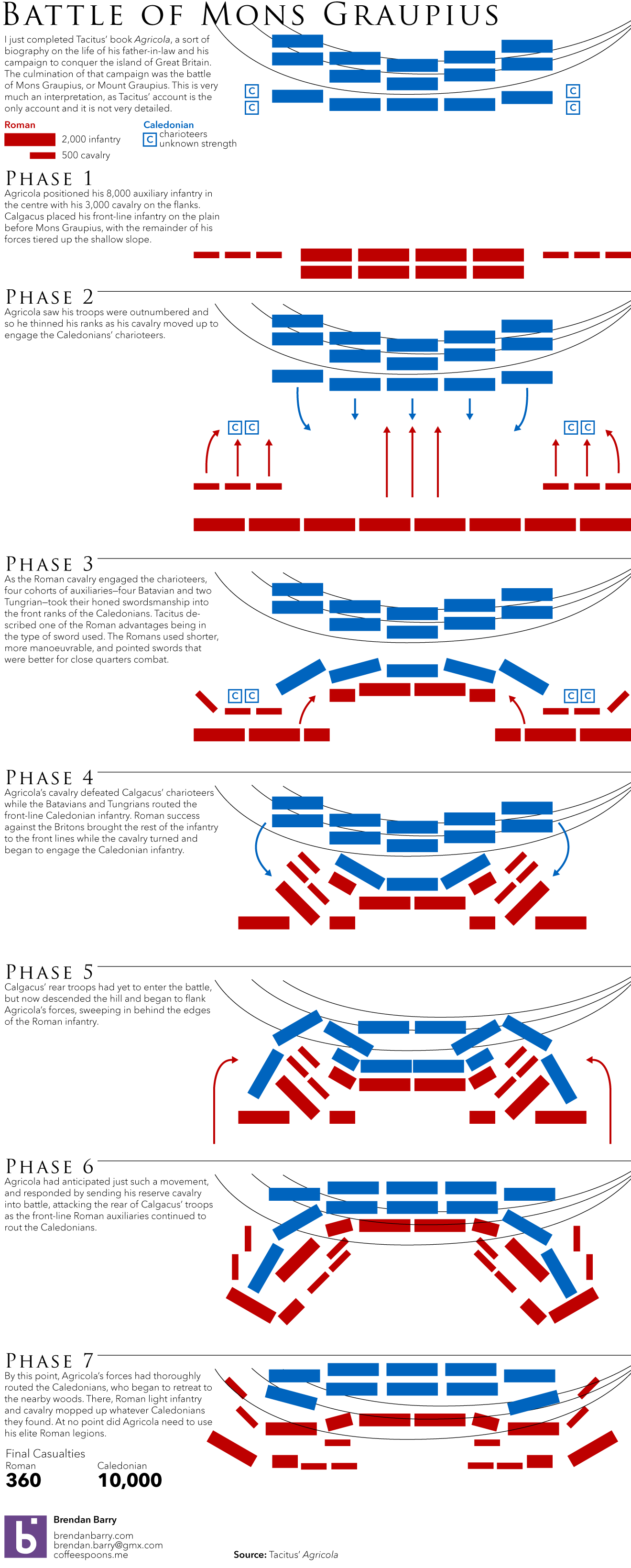

He says the front lines were made up of 8,000 auxiliary infantry and 3,000 cavalry. The actual Roman citizens—the elite legionaries—were kept in reserve. According to the story, the auxiliaries did all the dirty work. Tacitus boasts that the Romans killed 10,000 Caledonians while losing only 360 of their own.

That is an insane kill ratio. Honestly, it sounds a bit like propaganda.

The Caledonians were led by a guy named Calgacus. He’s famous for a speech he supposedly gave before the fight, containing the legendary line: "They make a desert and call it peace." It’s a banger of a quote. The only catch? Calgacus probably never said it. Tacitus likely wrote the speech himself to show off his own literary skills and to provide a "noble savage" perspective that critiqued Roman greed.

Tactical Nightmares: How the Fight Went Down

If we believe the Roman account, the Caledonians had the high ground. They were perched on the slopes of the mountain, looking down at the Roman lines.

The battle started with a massive exchange of missiles. Spears and arrows flying everywhere. The Caledonians used small shields and huge, cumbersome swords. These swords were great for slashing, but they were terrible in close-quarters combat because they didn't have a point.

Agricola saw this weakness.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

He ordered four batallions of Batavians and two of Tungrians to close in. These guys were specialists in hand-to-hand fighting. They used the bosses of their shields to smash into the faces of the Caledonians and used their short, stabbing swords to gut their opponents in the press of the crowd.

The Chariot Factor

The Caledonians brought war chariots. In the late first century, this was kind of old-school. Chariots were mostly a thing of the past in Continental Europe, but the Britons loved them.

They tried to use them to harass the Roman flanks, but the terrain at Battle of Mons Graupius was too rough. Tacitus describes the chariots getting tangled up in the uneven ground and colliding with their own infantry. It was a mess.

When the Caledonians on the hilltop saw their front lines crumbling, they tried to descend and outflank the Romans. Agricola had seen it coming. He held back four squadrons of horsemen who charged the flanking Caledonians and sent them into a full-blown retreat.

The chase lasted until nightfall.

Why the "Victory" Didn't Actually Stick

If the Battle of Mons Graupius was such a decisive win, why didn't Scotland become a Roman province?

This is where the story gets weird.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

After the battle, Agricola took some hostages, marched his troops back south, and then... he was recalled to Rome. The Emperor Domitian basically told him his time was up. Some say Domitian was jealous. Others think the Roman Empire simply realized that holding the Scottish Highlands was going to be way too expensive and difficult.

Within a few years, the Romans pulled back. They abandoned the forts they had built in the north, like the massive base at Inchtuthil. Eventually, they built Hadrian’s Wall, effectively saying, "Everything north of here is too much trouble."

The Calgacus Enigma

We don't even know if Calgacus survived. He vanishes from history the second the battle ends. In fact, we don't even know if Calgacus was his real name or just a title. "Calgacus" translates roughly to "The Swordsman."

It’s possible he was a real war leader who managed to melt away into the glens to fight another day. Or maybe he was a composite character created by Tacitus to give the Romans a worthy adversary.

What This Means for History Buffs Today

The Battle of Mons Graupius remains one of the great "what ifs" of the ancient world. If Agricola had stayed, or if the victory had been as total as Tacitus claimed, the entire culture of Northern Britain might have been Latinized. We might be speaking a Romance language in Aberdeen today.

Instead, the battle became a symbol of Caledonian defiance.

Even if the details were exaggerated, the event represents the furthest reach of the Roman eagle. It’s the high-water mark of the empire in Britain.

Actionable Insights for Researching the Battle

If you're looking to dive deeper into this mystery, don't just take the Roman side at face value.

- Read the "Agricola" by Tacitus: It's a short read and gives you the primary source material, but read it with a skeptical eye. Note how he portrays his father-in-law as a perfect hero.

- Look at Lidar Imagery: Modern archaeologists are using light detection and ranging (Lidar) to find hidden Roman camps in Scotland. Searching for "Lidar Roman Scotland" will show you the actual footprints of the army that fought at Mons Graupius.

- Visit the Gask Ridge: This is a line of early Roman signal stations and forts in Perthshire. It’s the best way to see the physical infrastructure Agricola left behind.

- Study the Auxiliaries: Most people focus on the Legionaries, but the Battle of Mons Graupius was won by the Auxiliaries (non-citizen soldiers from places like Holland and Germany). Researching the Batavians gives you a much better picture of how the Roman army actually operated on the frontier.

The mystery of the location will probably be solved eventually. Some farmer in the Grampians will turn over a stone and find a cache of Roman pilum heads. Until then, we’re left with Tacitus's vivid, bloody, and perhaps slightly fictionalized account of the day the Highlands ran red.