Robert E. Lee was tired. Honestly, that’s the simplest way to describe the state of the Army of Northern Virginia by April 1865. They were hungry, they were surrounded, and the dream of a Confederate nation was basically bleeding out in the mud of Virginia. Most people think the Battle of Appomattox Court House was just a formality—a quick meeting in a parlor where everyone acted like gentlemen and went home. That’s not quite right. Before the famous meeting at the McLean House, there was actual, desperate fighting. Men died on those hills on April 9th, 1865, fighting for a cause that was already dead, simply because the messages hadn't caught up with the bullets yet.

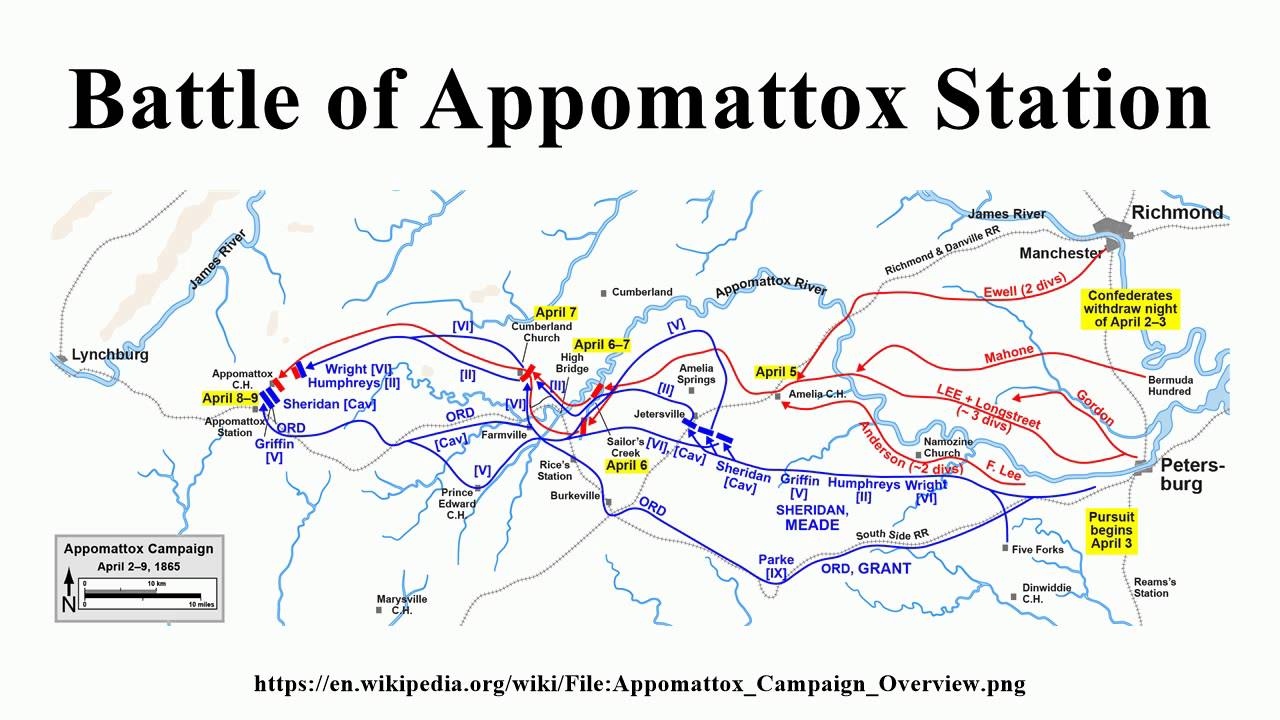

It wasn't a grand, sweeping Napoleonic clash. It was a scramble. Lee was trying to reach Lynchburg to get supplies. He thought he only faced Union cavalry under Philip Sheridan. He was wrong.

The Morning the World Ended for the Confederacy

Imagine the scene. It’s dawn. Major General John B. Gordon, a man who had survived more wounds than most people have birthdays, prepares his Confederate Second Corps for one last push. They actually succeeded at first. They cleared the Union cavalry from the ridge. But as the fog lifted, Gordon saw something that probably made his heart sink into his boots. Behind the thin line of cavalry stood solid walls of Union infantry—the XXIV and V Corps. They had marched all night to get there.

"Tell General Lee I have fought my corps to a frazzle," Gordon famously sent back. He was done. There was nowhere left to run.

The Battle of Appomattox Court House wasn't just a military defeat; it was a logistical collapse. The Confederates hadn't eaten a full meal in days. Horses were dropping dead from exhaustion. When Lee heard Gordon’s report, he realized the endgame had arrived. He famously remarked, "There is nothing left for me to do but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths." It's a heavy line, but he meant it. For Lee, surrender was a fate worse than a bullet.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

Why the Location Was Kind of Weird

Appomattox Court House isn't the name of a building. It's the name of the village. It's a common mistake. People think they surrendered in a courthouse, but they actually used the private home of Wilmer McLean. This is one of those "truth is stranger than fiction" moments in history. McLean had originally lived in Manassas. The first major battle of the war, Bull Run, was fought literally on his farm. A cannonball once flew through his kitchen. He moved to this quiet backwater village to get away from the war.

Then, four years later, the war ended in his front parlor. You can't make that up.

The Terms That Changed Everything

Ulysses S. Grant was a messy guy. He showed up to the meeting in a mud-spattered private's uniform because his dress trunk was miles away. Lee, meanwhile, was dressed in his finest gray uniform, complete with a sash and sword. The contrast was incredible. If you were just looking at them, you’d think Lee was the victor.

But Grant held all the cards. Yet, he wasn't interested in humiliation. The terms he wrote out for the Battle of Appomattox Court House surrender were surprisingly generous.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

- Confederate officers could keep their sidearms.

- Men who owned their own horses or mules could take them home to "put in a crop."

- Grant even sent 25,000 rations to the starving Confederate troops.

This wasn't just kindness. It was high-level politics. Grant knew that if he treated them like criminals, the war would turn into a centuries-long guerrilla conflict. By treating them as fellow countrymen who had gone astray, he paved a (very rocky) road toward reunification.

The Myth of the "Clean" Surrender

We like to think that once Lee signed that paper, the war stopped. It didn't. News traveled slow. Fighting continued in North Carolina under Joseph E. Johnston for weeks. The last land battle happened in Texas in May. The CSS Shenandoah didn't even stop raiding Union ships until November.

Also, the "Silent Witness" doll is a detail most people miss. When the generals left the McLean House, Union officers started buying—or just taking—furniture as souvenirs. One officer took a rag doll belonging to McLean’s daughter, Lula. It’s still known as the "Silent Witness" to history. It's a reminder that this was a person's home, not just a set for a history book.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Tactics

The fighting on the morning of April 9th was sharp. The Confederates actually captured two brass cannons. For a moment, it looked like they might break through. But the Union army's sheer numbers were overwhelming. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, the hero of Little Round Top, was there. He witnessed the Confederates stacking their arms.

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

In a move that deeply annoyed some of his superiors, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute the surrendering Southerners. Not a salute to the Confederacy, but a "salute of honor" to a defeated foe. It was controversial then, and it's still debated by historians today. Did it help heal the country, or did it start the "Lost Cause" myth?

Expert Nuance: The Role of the USCT

One thing often left out of the Battle of Appomattox Court House narrative is the presence of United States Colored Troops (USCT). Black soldiers were part of the force that blocked Lee’s escape. Think about the poetic justice of that. Men who had been enslaved just years prior were now the iron wall that forced the surrender of the man defending the system of slavery. Their presence was a living testament to how much the war had changed since 1861.

Real Lessons from Appomattox

If you go to the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park today, it’s hauntingly quiet. The village is restored to look exactly like it did in 1865. Walking those dirt roads, you realize how small the space was. The fate of four million enslaved people and the future of a continent were decided in a room no bigger than a modern studio apartment.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're planning to study or visit the site of the Battle of Appomattox Court House, don't just look at the McLean House.

- Walk the North Carolina Monument trail: This is where the last shots were actually fired. It gives you a sense of the terrain Gordon’s men had to climb.

- Check the Parole Passes: Look up the digitized records of the "Appomattox Paroles." You can find names of ancestors who were there. It makes the history personal.

- Read "The Passing of the Armies" by Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain: It's his firsthand account of the surrender. It's flowery, sure, but it captures the raw emotion of the day in a way a textbook never will.

- Examine the "McLean House Furniture" at the Smithsonian: If you want to see what Grant and Lee actually sat on, several pieces are in D.C. now.

The surrender wasn't just the end of a war; it was the birth of a version of America that finally, painfully, began to live up to its own rhetoric. It was messy, violent, and complicated. Just like the battle that preceded the peace.

To truly understand this event, your next step should be to look into the "Surrender at Bennett Place." While Appomattox is more famous, the surrender of Joseph E. Johnston to William T. Sherman in North Carolina actually involved more troops and was far more politically tense. Comparing the two shows just how much Grant’s personal restraint influenced the outcome at Appomattox.