History is full of weird ideas that actually worked, and then there’s Project X-Ray. Honestly, it sounds like something a six-year-old would dream up after watching a cartoon. You take a bomb, stuff it with thousands of hibernating bats, strap tiny incendiary devices to their chests, and drop the whole thing over a city. It’s wild. But in the early 1940s, this wasn't just a joke; it was a multimillion-dollar project backed by the U.S. military. The bat bomb world war 2 project was a serious attempt to win the war using nature's own night flyers.

It all started with a dentist named Lytle S. Adams. He was a friend of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and had a particular fascination with the Mexican Free-tailed bat. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Adams was vacationing in New Mexico, watching bats fly out of Carlsbad Caverns. He had a thought. What if these things could carry fire? He wrote a letter to the White House. Most people would have laughed it off, but this was 1942. The world was on fire, and the military was desperate for any edge. President Roosevelt actually sent a memo to Colonel William J. Donovan, the head of the OSS, saying, "This man is not a nut."

Why the Military Actually Liked the Idea

You have to understand the architecture of Japanese cities at the time. They weren't made of steel and concrete like modern Manhattan. Most buildings were wood, paper, and bamboo. They were essentially giant tinderboxes. The bat bomb world war 2 concept relied on the bat's natural instinct to find dark, secluded places to hide during the day. If you released them over a city at dawn, they would fly into attics, under eaves, and into the nooks of traditional Japanese homes.

Each bat would carry a tiny napalm-filled canister. We’re talking about a surgical-grade precision strike, but on a massive, chaotic scale. Once the bats settled in, a timed fuse would ignite the incendiary. Suddenly, you’d have thousands of small fires starting simultaneously across an entire city. Firefighters wouldn't stand a chance. It was designed to be a weapon of mass disruption, turning a city’s own housing against itself.

The Science of Shoving Bats into Bombs

The logistics were a nightmare. Louis Fieser, the chemist who actually invented napalm, was brought in to design the tiny incendiary devices. He had to create something that weighed less than an ounce but could still burn hot enough to start a structure fire. He settled on a cellulose nitrate housing filled with thickened gasoline.

👉 See also: What Is Hack Meaning? Why the Internet Keeps Changing the Definition

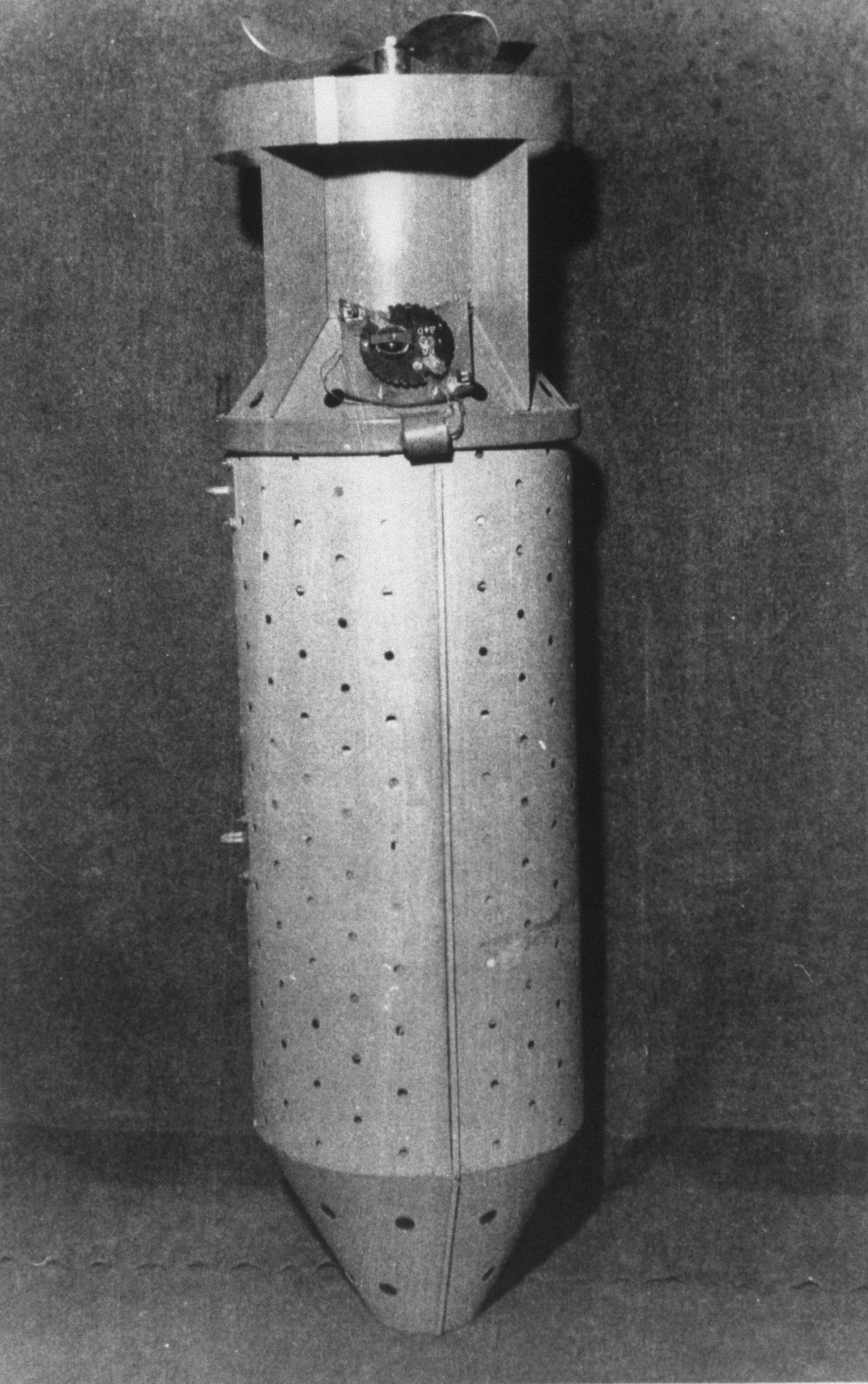

Then there was the problem of the bats. You couldn't just throw them out of a plane; they’d freeze or die from the pressure change. The solution was a specialized casing that looked like a regular bomb but contained internal trays. The bats were cooled down to a hibernating state so they would stay still. Upon release, a parachute would deploy, and as the bomb descended, the trays would open, the air would warm the bats up, and they’d wake up mid-air and fly away. Basically, it was a biological delivery system for thousands of tiny arsonists.

That One Time the Bats Burned Down an Air Base

The project wasn't all theory. During testing at Carlsbad Army Airfield in May 1943, things went sideways in a way that would be funny if it wasn't so dangerous. Some of the bats were accidentally released while they were "armed." They did exactly what they were bred to do. They found dark places to hide. Specifically, they flew under the eaves of the barracks and the general’s car.

The result? The airfield was largely incinerated. The bats burned down the barracks, a hangar, and several other structures. It was a disaster for the base, but for the proponents of the bat bomb world war 2 project, it was actually proof of concept. It worked perfectly. It just worked on the wrong people.

Marine Corps Involvement and Final Testing

After the Army grew tired of the "bat men," the U.S. Marine Corps took over the project in late 1943. They moved testing to Dugway Proving Ground in Utah. They built a "Japanese Village"—a full-scale replica of a Japanese neighborhood—to see just how much damage these creatures could do.

✨ Don't miss: Why a 9 digit zip lookup actually saves you money (and headaches)

The results were terrifyingly effective. The Chief of Incendiary Operations at Dugway noted that the bat bombs were more effective than standard incendiary bombs. While a regular bomb might create a single large fire that could be targeted, the bats created thousands of "micro-fires." The report suggested that weight-for-weight, the bat bomb was more destructive than any other conventional weapon available at the time.

Why We Never Actually Used It

If the tests were so successful, why didn't we see bats over Tokyo? It mostly came down to timing and the Manhattan Project. By 1944, the bat bomb world war 2 project had already cost about $2 million (which was a lot more then than it is now). Admiral Ernest J. King eventually cancelled it because it wasn't going to be ready for combat until mid-1945.

At the same time, the development of the atomic bomb was accelerating. The military realized that a single B-29 carrying one "Little Boy" was much more efficient than a fleet of planes carrying temperamental bats that might decide to fly the wrong way if the wind changed. The project was shelved, and the bats were sent back to their caves, likely unaware they were almost the face of modern warfare.

The Ethics of Biological Chaos

Looking back, the bat bomb represents a strange intersection of biological warfare and psychological terror. It was a weapon that exploited the very nature of a living creature to cause destruction. While it’s often remembered as a "wacky" footnote, the intent was deadly serious. It highlights the desperation of the era—a time when no idea was too strange if it promised an end to the conflict.

🔗 Read more: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

The project also tells us a lot about the bureaucratic nature of war. You had some of the most brilliant minds in the country, like Louis Fieser, spending months trying to figure out how to glue a bomb to a bat’s chest. It’s a reminder that innovation isn't always a straight line; sometimes it’s a weird, flapping detour into a New Mexico cave.

What to Take Away From the Bat Bomb Saga

The story of the bat bomb world war 2 project isn't just a "believe it or not" trivia fact. It’s a case study in non-linear thinking. It shows that even in the most rigid systems—like the U.S. Military—there is room for wild experimentation.

If you're interested in digging deeper into this specific era of experimental weaponry, here are a few things you can do to get the full picture:

- Visit the source: If you're ever in New Mexico, the Carlsbad Caverns National Park has great exhibits on the local bat populations and their history. It's the best place to visualize the scale of where these bats came from.

- Read the primary reports: Look up the "Project X-Ray" declassified reports available through the National Archives. Seeing the cold, clinical way the military described "bat dispersal" is fascinating.

- Research the "Japanese Village" at Dugway: There are some incredible photos of the replica cities built in the desert for these tests. It puts the scale of the planned destruction into a much grimmer perspective.

- Compare with other "weird" weapons: Check out Project Pigeon (B.F. Skinner’s attempt to guide missiles with birds) or the Great Panjandrum. It helps put the bat bomb in context as part of a larger trend of eccentric WWII engineering.

The bat bomb reminds us that the line between genius and madness is often just a matter of whether the project gets funded or cancelled. In this case, the atomic age simply moved faster than the bats could fly.